When advertising executive Michelle Gilson thinks about sexism in her business, she thinks about silly girls. You’ll know the trope: the attractive young woman who is simultaneously independent and idiotic, doing silly things in hysterical fashion because apparently that is all she is good at.

Gilson, the planning director at Adam & Eve/DDB, the agency best known for its John Lewis Christmas ads, cites a recent “Regret Nothing” campaign for Diet Coke. Its bash at empowerment arguably fell flat with the “Impulsista”, a woman who “knows what she wants and acts on her impulses”.

“In one ad, a girl going round town has a ladder in her tights, so all her friends put ladders in their tights, too,” Gilson says. “I don’t know anyone in their right minds who would do that – it just paints women as these ridiculous creatures.” She also takes exception to a recent advert featuring musician Nicole Scherzinger, who seems to become sexually aroused by yoghurt.

If this sounds familiar, you may take comfort from the news that one of the world’s biggest companies has promised to take such sexist stereotypes out of its commercials. On the other hand, you might reflect on the fact that, on the day the announcement was made, much of the gossip at the industry jamboree where Unilever sold this vision focused on two sexism scandals.

Unilever, which has a £6.3bn annual ad budget and is responsible for the Lynx effect, as well as countless shampoo hair-flicks and an Asian mayonnaise brand called Lady’s Choice, announced the results of a two-year study at the Cannes Lions festival in France.

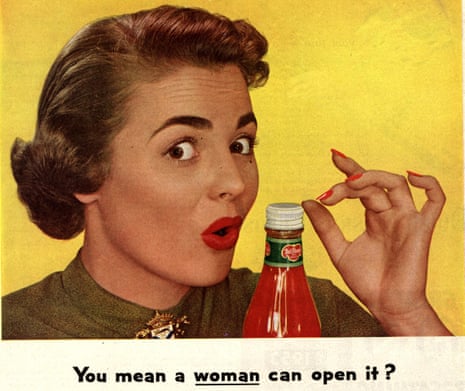

“The time is right for us as an industry to challenge and change how we portray gender in our advertising,” Unilever’s chief marketing officer, Keith Weed, said on Wednesday, half a century after misogynist marketing came to define the Mad Men era.

The company’s survey of ads and consumers revealed that 40% of women do not recognise the faces being reflected back at them. The study provided a possible explanation; of the women the ads featured, 3% were portrayed in leadership roles, 2% were intelligent, and 1% were funny.

“The media – and advertising specifically – have been slow to reflect the changing shape of gender identity and often depict, at best, a current view of society, and sometimes a backward view,” Unilever added.

That backwardness was made evident when Cindy Gallop, a British advertising consultant and industry veteran, called out sexism at the festival. First she tweeted a photo of a book about advertising given to delegates in a goody bag. The Case for Creativity by James Hurman lists its nine biggest contributors on the inside cover. They are all men. Weed wrote the foreword.

It's 2016, @vaynermedia @thrillist. This is not how you party at @cannes_lions. #canneslions #changetheratio pic.twitter.com/jF50tdPe0p

— Cindy Gallop (@cindygallop) June 22, 2016

“This book, being given out to every creative in Cannes, was saying creativity is the sole province of men,” Gallop says. “More horrifying was that James said it hadn’t occurred to him until he saw my tweet. That shows you how pervasive unconscious bias is in our industry. You cannot be who you cannot see.”

Gallop, who despairs of “young male morons in beer ads, and hapless husbands” as much as she does female stereotypes, later shared an invitation to a party sponsored by a digital agency. Wyclef Jean performed. The event was “for attractive females and models only”, the email said. They were required to submit “recent untouched photos”.

The mortified agency blamed a contractor, but Gallop says sexism is as rampant as it was when she started in advertising in 1985 (she later managed accounts for Coca-Cola and Ray-Ban). “And it doesn’t matter how well-meaning Unilever’s report is,” she adds. “Nothing changes until the gender of leadership is balanced.”

A report published by the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising in January showed that women occupy less than a quarter of creative or design roles in UK advertising. “And if you’re a female creative, you have to get work approved by a creative director, 90% of whom are men,” says Gilson.

The effects of this imbalance are hard to resist – or even to see: “Even I have sat in a creative review meeting and thought a script is great and then got home and thought, ‘Shit, that women is in this or that stereotypical role’. It’s a blind bias and we all have to open our eyes,” she says.

Change is afoot, even if the business rather than moral case is compelling male-dominated boardrooms. Unilever brands including Dove have helped to launch the age of “femvertising” and its forest of hashtags, including #GirlsCan (makeup), #ShineStrong (shampoo) and #LikeAGirl (sanitary pads). These ads try to sell stuff by reflecting the real world and calling out its imbalances, sometimes striking an awkward tone. Even Lynx got a reboot this year with “Find your Magic”, a slightly broader depiction of masculinity.

“Companies are starting to realise we can’t stick with what we have; we risk alienating the consumer and affecting the bottom line,” says Danielle Todd, research manager at Relish Research, a London consultancy. Todd says the message from focus groups is clear: “Young men and women trying to find themselves don’t want to see stereotypes represented in the products they like – they want to see themselves.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion