Stress is often perceived as the villain of contemporary culture: the nagging tension that keeps us chained to our desks during the day, awake all night, and makes us dangerously unhealthy.

But Ian Robertson, a cognitive neuroscientist at Trinity College Dublin and author of the upcoming book ‘The Stress Test: How Pressure Can Make You Stronger and Sharper,” says that, while too much stress can be debilitating, a moderate amount is extremely good for the mind.

He explains that stress causes the brain to secrete a chemical called noradrenaline. The brain doesn’t perform at its best with too little or too much of this chemical. But “there’s a sweet spot in the middle where if you have just the right amount, the goldilocks zone of noradrenaline, that acts like the best brain-tuner.”

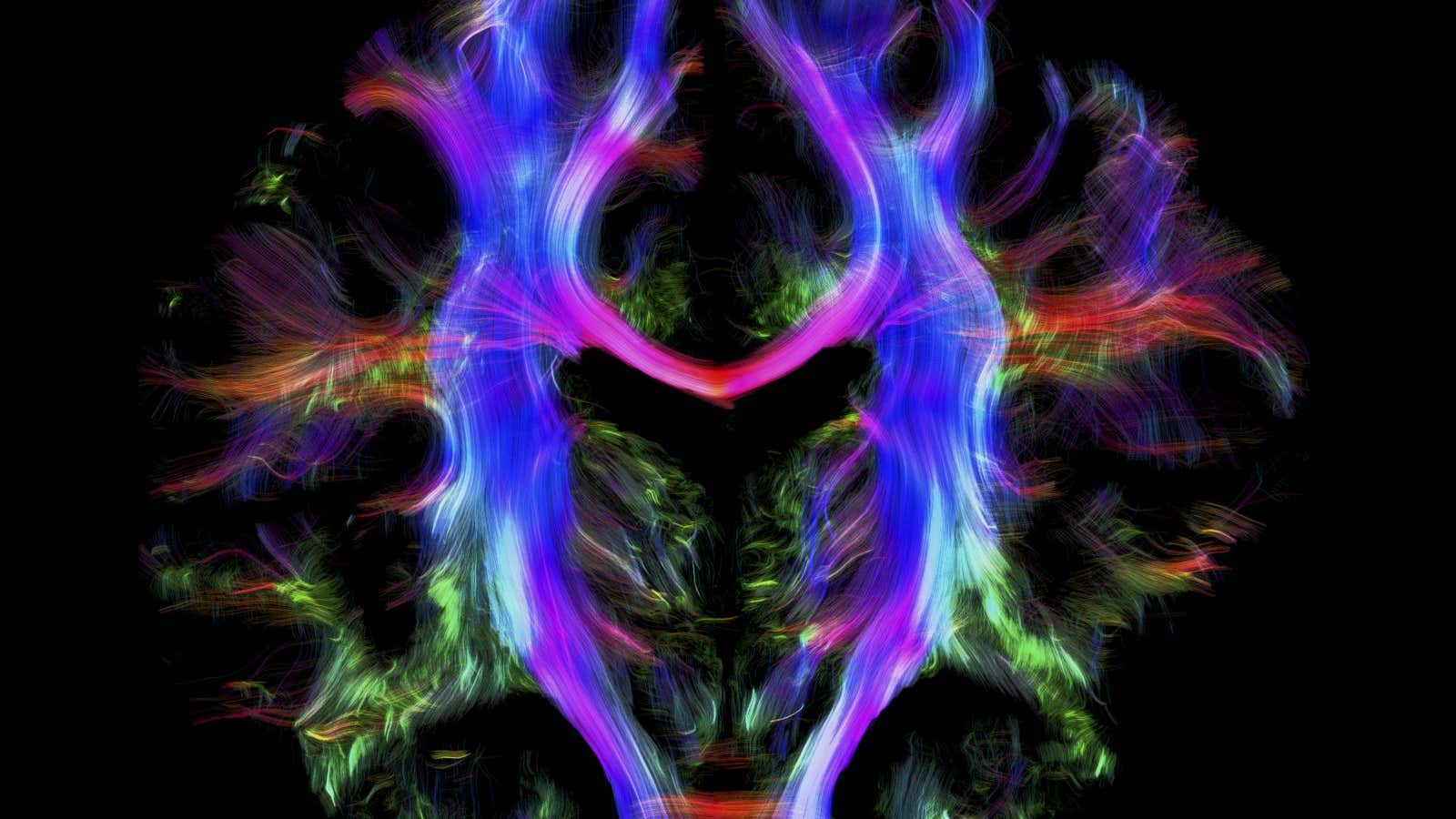

Essentially, noradrenaline helps the different areas of the brain communicate smoothly, and also helps make new neural connections. “As long as it’s not too stressful, we can build stronger brain function. If we have stronger brain function we’ll be happier, we’ll be less anxious, less depressed and we’ll be smarter,” adds Robertson.

Not everyone is able to cope well with stress and harness its productive potential. Some become overly anxious and find stress to be an insurmountable burden rather than a stimulant. However, Robertson says that there are distinct techniques we can learn in order to reframe our approach to stress. “We can change the chemistry of the brain just as much as any antidepressant or anti-anxiety drug can, but we have to learn the habits to do that,” he says.

Training the brain to thrive in stressful situations

The first, most important factor that determines our approach to stress is whether we have a “fixed” or “growth” mindset. This is based on the work of Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck, who says that the ability to believe that we can change allows us to do so. By contrast those with a “fixed” mindset are far more likely to remain stuck.

In the case of coping with stress, someone with a fixed mindset might believe that they inherit their anxious attitude from a parent and so there’s nothing that can be done about it. This can be “fatalistic,” says Robertson, and so it’s important to examine the source of your beliefs about your emotions.

For those who believe they have the ability to change their approach to stress, Robertson points out that the same symptoms—such as a dry mouth and racing heart—apply to both fear and excitement. Studies have found that when people are put in a stressful situation, such as singing karaoke or answering math questions in front of a panel, rather than trying to stay calm, they perform far better when they simply tell themselves they’re excited.

In line with this, Robertson says it helps to conceive of stress as a challenge rather than a threat. “Making that mental switch, just re-framing it reduces stress and improves performance,” he adds. And finally, faking it until you make it really does work. “If you adopt the external manifestation of confidence and positivity, you can trick your brain into creating the mental correlates of that fake external posture,” says Robertson.

Stress works like the immune system

There can be a downside to constantly avoiding stress, especially early in life. Robertson says that the stress response system seems to work like the immune system, in that it gets stronger if it has a little practice.

“Children need to experience a certain amount of adversity so that both their body and mind becomes toughened and resilient,” he says. Too much adversity can be harmful, but Robertson adds, “There’s a sweet spot of adversity that someone can have, particularly in the first two decades of their life that seems to make them emotionally robust.”

Studies have found that children who were adopted at a young age (which is classified as moderate early life stress, compared to children who spent several years in care before being adopted) grow up to have lower levels of stress hormone cortisol in response to stressful situations than US children who’d had very little adversity. Similarly, those who’ve experienced adversity have been found to suffer less physical impairment from chronic back pain than those who lived cushy lives.

And so learning to cope with stressful situations at a young age can be extremely beneficial. While nobody wants to be constantly chasing after stress, a little bit of stress can be a powerful motivator.

“Many comedians and performers worry if they don’t feel that edge of anxiety before a performance,” says Robertson. “Tiger Woods says if he doesn’t feel anxious before a match, he knows he’s going to do badly.”