I have a theory about why kids love dinosaurs. You might think it’s their size, their ferocity, the number and sharpness of their teeth. It is all of these things, but it is something else, too.

Dinosaurs are remote from us in time. They belong to an alien realm. They ruled this planet for more than 150 million years, the longest such reign ever achieved by Earth’s megafauna. We know this because their bones froze into stone, and became fossils. But the dinosaurs left only a few of these remains, and they are, after all, mostly skeletal.

Everything else must be pieced together, or imagined.

A dinosaur is a muse, then. To contemplate a dinosaur is to slip from the present, to travel in time, deep into the past, to see the Earth as it was tens, if not hundreds, of millions of years ago, when the continents were nearer, when the forests and oceans teemed with strange plants and creatures. In childhood, the mind is alive to the thrill of that perspective shift.

And in adulthood, too, which is why there is an entire genre of art dominated by dinosaurs. Paleo art, it is called, and it has a sophisticated critical following. There are coffee-table books. There is even a single-serving blog, called Echoes from the Antediluvian, where every week, writer Benjamin Chandler uses a piece of paleo art as a writing prompt.

Paleo art’s master practitioners are in high demand. They make museum murals. They illustrate scientific papers and children’s books. And they do more than paint dinosaurs. John Gurche, America’s most famous paleo artist, specializes in hominins, like the recently discovered Homo Naledi.

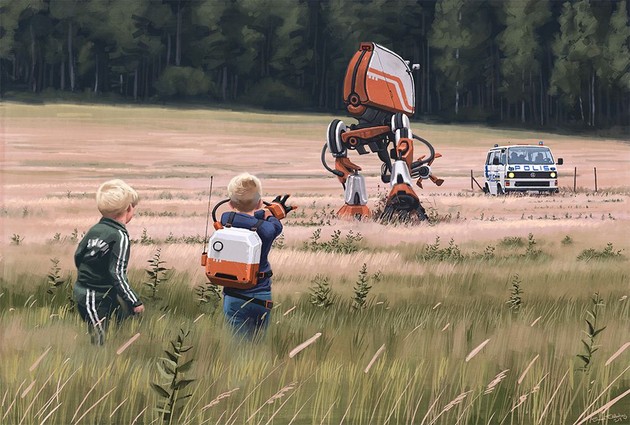

Simon Stålenhag is not a famous paleo artist. He is a Swedish digital illustrator, and he tends to work in science fiction. He will soon release a book of illustrations in the U.S., a collection of moody glimpses into Swedish suburbia, circa 1985, overlaid with retrofuturistic technologies:

A few years ago, as Stålenhag was putting the final touches on the book, he “rediscovered dinosaurs,” he told me. Stålenhag loved paleontology as a kid, but like many of us, he forgot about dinosaurs during adolescence and early adulthood. At the age of 25, he came back to them, after developing an intense interest in natural history.

“I read about these new fossils from China, the feathered dinosaurs,” Stålenhag told me. “I had always loved birds, and wildlife illustrations of birds, in particular.” He decided to make a few sketches.

In early 2013, Stålenhag reached out to Sweden’s Natural History Museum. “I asked if there was anything I could help with,” he says. “I told them I didn’t care what it was for. I just wanted to paint dinosaurs.” As it happened, the museum was overhauling its dinosaur exhibit. Stålenhag sent over his sketches. Shortly thereafter, they commissioned him to do each of the exhibit’s digital paintings. There were 28 in all.

Scroll back up to the image at the top of this page. Look at the way Stålenhag frames the T-Rex. He sets you back at a distance. He reminds you that you’re eavesdropping, that this world isn’t yours. You feel an instant affinity with the nervous herd of herbivores in the foreground. Past the T-Rex and the carnage of its kill, birds are scattering. Dinosaurs themselves scattered into birds, to survive the asteroid and the volcanoes that followed. In the background, the stratified cliffs evoke geologic time.

I asked Stålenhag if his paleo art was influenced by other artists. He named two: Lars Jonsson and John Conway. Jonsson is an ornithologist, who mainly illustrates birds. “For him, every bird is an individual,” Stålenhag told me. “He observes them in their natural environments.” Jonsson’s influence can be seen in Stålenhag’s close-ups, like this image of three archeopteryx:

I asked Stålenhag if he worked closely with paleontologists, expecting him to say yes. He said their input was limited. “I did a lot of research on the dinosaurs,” he told me. “The information is easy to come by. You don’t have to ask a professor. You can find it online. But it’s hard to get everything right. I had to redo some of them.”

In the image below, Stålenhag painted a different pair of dinosaurs. The curator told him the terrain was too dry for that species. So he switched in two coelophysis instead.

A few scientific inaccuracies survived the editing process. In one image, Stålenhag tells me, the vegetation is off by tens of millions of years. “It’s not a schematic, or a scientific paper,” he says. “And anyway, I don’t like illustrations that are like blueprints. They lack atmosphere.”

Stålenhag told me he wants to make more paleo art, but not for a museum. “I’ve been thinking about doing more dinosaurs,” he told me. “I want to see if there’s a way to explore that with science fiction.”

And not only dinosaurs. The whole of natural history has captured Stålenhag’s imagination. Whatever it was that he read, back when he was 25, summoned something long buried. The childhood thrill of thinking deep into time, forward or backward.

“There are so many scenes from Earth’s history that are interesting,” he told me. “Like when the planet was bombarded by icy comets, shortly after it formed. Or when our moon was much closer. What did that look like? What was it like when our solar system was born? How dense was the disk of dust around the sun? There are just so many things to explore.”

The rest of Stalenhag’s paleo art can be seen here, or at the Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet in Stockholm.