Washing up on the shores of San Salvador island on 12 October 1492, Christopher Columbus described the Amerindian natives he first met as "sweet and gentle". Too trusting, perhaps, for the seeds of exploitation were sown in those early days of the Caribbean adventure. Spain's fledgling empire builders would soon begin to make a distinction between the tractable Taino and the hostile Carib, depicting the latter as violent and cannibalistic. Bringing with them disease, military power and evangelistic zeal, the Europeans had decimated the indigenous population before the end of the 16th century. Needing a commodity that would make them rich, and the labour to produce it, they would quickly turn to sugar and African slavery as the sources of their future prosperity.

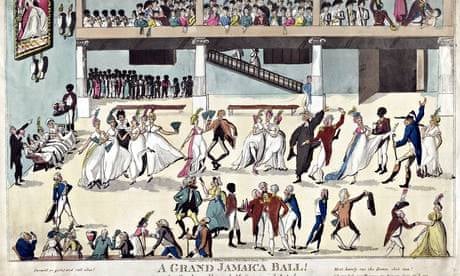

By 1700, English ships alone had transported some 400,000 slaves from the west coast of Africa to work on sugar plantations in Caribbean colonies like Barbados and Jamaica, and millions would be enslaved during the 18th century. Olaudah Equiano, a North American slave who eventually bought his freedom, published a horrifying account of his experiences in 1789, starting with the notorious "Middle Passage" at sea, when "the shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying" filled him with dread.

But the late 18th century also witnessed the beginning of the end. Just as France experienced its own revolution, slaves on the French colony of Saint-Domingue overthrew the plantation owners and established the independent Republic of Haiti in 1804. Starting with Britain in 1834, Europe's governments would gradually abolish slavery throughout the 19th century. Yet the legacy of slavery and the racism it bred would persist until the modern day.

For all the common threads running throughout the story of the Caribbean, the experiences of its many countries have been wildly divergent, as anyone travelling from Haiti to the former Spanish colony of Cuba would quickly attest. Carrie Gibson manages to weave 500 years of complex history into a brilliantly coherent and thematic narrative in Empire's Crossroads, her first book, motivated by a "nagging disquiet" that so much atrocity underpinned the cultivation and sale of a commodity as inessential as sugar. As she recounts in the introduction, a childhood spent in America's deep south, scarred by its own history of slavery and racial prejudice, also imbued her with an enduring curiosity about the neighbouring region and the different path that discovery, exploitation and, ultimately, emancipation took on its islands.

Unsurprisingly, then, Gibson's writing is tinged with a sense of indignation at the wrongdoings that were perpetrated in the Caribbean, from the moment the Portuguese and Spanish first arrived until America's invasion of Grenada as recently as 1983. Slavery was irrevocably bound up with the mercantilist trading system on which Europe grew fat between the 16th and 18th centuries, and it was only when this fell out of favour in the more laissez-faire 19th century that abolition gained momentum. Without necessarily belittling the efforts of abolitionists such as William Wilberforce, Gibson makes readers face up to the unsettling likelihood that economic changes – rather than growing public sympathy for the plight of the slaves – brought this form of exploitation to its end.

A coda about the unsavouriness of present-day Caribbean tourism, with "black people [serving] white people in an uncomfortable echo of a not-forgotten past", is a reminder that other forms live on. According to the World Bank, around 80% of the money tourism makes in Jamaica does not stay on the island, flooding instead into the coffers of multinational resorts.

At heart, Gibson may be diametrically opposed to empire apologists like Niall Ferguson, but she can also write about empire with a broad perspective, placing the history of the Caribbean in the context of major global developments. The Protestant Reformation emboldened northern Europeans to disregard papal orders and enter West Indian waters. The French Revolution was an important catalyst for the uprising on Saint-Domingue that led to Haitian independence. And Napoleon's invasion of Spain helped bring about the collapse of its New World empire, which vanished entirely when Cuba and Puerto Rico fell under American influence in 1898.

That does not mean events in the Caribbean have merely been a sideshow. As its title implies, Empire's Crossroads puts the region at the centre of clashes between the European powers (although one wonders if it should have been called Empires' Crossroads), noting the influence it has had – for good or ill – on industrialisation, the concept of human rights and more. As far as Gibson is concerned, "everything was created in the West Indies. The Europe of today, its financial foundations built with sugar money – the factories and mills … the idea of true equality … and even globalisation and migration."

Reading her strikingly assured debut, this reviewer found it hard to disagree.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion