“Fantasy” is the right word for British politics as spring sputters into summer, with Brexit’s chariot hurrying near. Not the good kind, mind you. Rather than a pleasant daydream, we’re dealing instead with collective delusion, in which cabinet ministers, walled off from reality, waste weeks debating customs plans that the EU has already rejected.

So it’s not surprising that a senior EU figure has dismissed the government’s entire approach to the negotiations as make believe. “To paraphrase The Leopard by Tomasi di Lampedusa,” the official said, “I have the impression that the UK thinks everything has to change on the EU’s side so that everything can stay the same for the UK.” As if to underline the point, Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, issued his own warning about the increasing likelihood of a “disruptive Brexit”.

In one sense the paralysis on the UK side is understandable. All of the options are bad. The boss of HMRC told MPs this week that so-called “max-fac” would cost £20bn; a customs partnership would cost £3bn. The only no-cost solution – remaining in the customs union and single market – has already been rejected on the basis that the public hates EU regulations like the ban on mobile phone roaming charges, and loves free trade deals, with their promise of chlorinated chicken and expensive medicines for all. Even as they publicly trumpet the benefits of their preferred plans, it’s hard to imagine the ministers involved are not privately frightened to take the plunge. Every course of action will result in increased poverty and bureaucracy. Hence the deadlock, hence the retreat into fantasy.

For some, however, Brexit isn’t the problem. It’s the helpless flapping of politicians that is ruining everything. If only they were less craven, less factious, less captured by the Whitehall system. Then everything might have been alright.

Dominic Cummings, who led the official Vote Leave campaign, published an open letter to Tory MPs and donors this week. He took the government to task, accusing them of having “botched” Brexit by triggering article 50 without adequate preparation. “This immediately closed many positive branching histories and created major problems,” he wrote. He further complains that “The government promised … to do a number of things that are logically, legally and practically incompatible including leaving the single market and customs union, avoiding ‘friction’ and changing nothing around the Irish border (as defined by the EU), and having no border in the Irish Sea.”

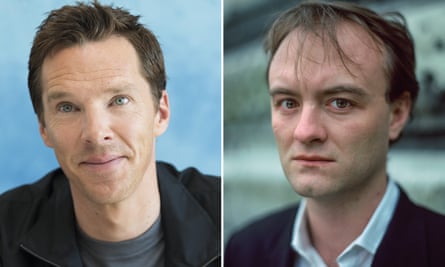

Cummings is an intriguing character – he was described by David Cameron as a “career psychopath” and has a reputation as an extremely clever but irascible free-thinker. (He’s going to be played by Benedict Cumberbatch in a film about the referendum). What’s less often recognised is that he is a utopian, someone for whom reality just isn’t good enough. And his “vision” of a revolution in governance played a not insignificant part in creating the dystopia in which we currently languish.

He backed leave because he wanted to “break the system open”, and believed “alternatives to the EU and UN are vital if we are to develop the international cooperation on big problems that we need”. Britain could lead the way. Those “positive branching histories” are the possible routes to a new Jerusalem he believed Brexit could open up. The roads the country’s leaders could take if they were equal to the challenge and grasped the nature of the prize.

The problem is they were always vastly outnumbered by “negative branching histories”. We have the system we have. That doesn’t mean it can’t be changed. But the chances of it being swept away in a tsunami of enlightenment are negligible. No matter how much you might wish it otherwise, many of our successful politicians will also be craven and factious. Faced with the complexity of unravelling 40 years of legal, political and economic cooperation, the UK government was always going to stumble. Theresa May, or whoever else became PM, would naturally come under intense political pressure to trigger article 50 quickly. A split vote was always going to mean there would be no mandate for revolutionary change. In other words: Brexit could only have worked as a utopian fantasy. As a project in reality, it was doomed from the start.

I don’t know why Cummings et al failed to reckon with these realities. Maybe they thought the gamble, even with those odds, was worth it. But that’s reckless, and brings to mind Isaiah Berlin quoting Alexander Herzen: “Do you truly wish to condemn the human beings alive today to the sad role of caryatids supporting a floor for others some day to dance on?”

Because we have been condemned – to lower standards of living, less consumer protection, less cooperation in the fields of science, the environment and diplomacy. And Cummings’ blame game seems a bit of a fantasy itself, given that it was his idea of “perfect” that turned out to be the enemy of what was good for the rest of us.