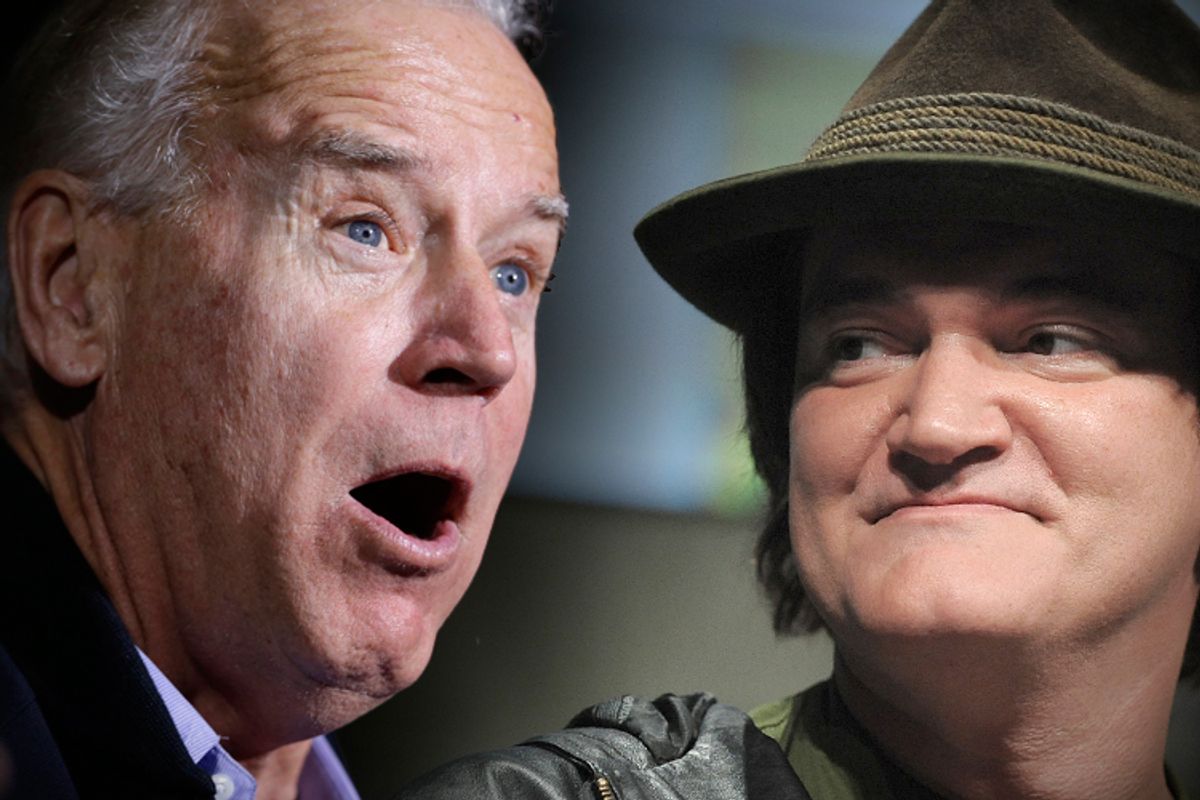

Earlier this week, Vice President Joe Biden held a meeting at the White House with several big-shot representatives of the entertainment industry. On the same day, Quentin Tarantino had a TV interview go off the rails when a British journalist steered away from the masturbatory puffery of movie junkets and tried to get him to talk about something serious.

Those are pretty much the last factual statements you’re getting from me today, because we now enter the netherworld of opinion, contested research, prejudice and prevarication surrounding the issue of media violence, in which nobody knows anything and every utterance should be treated as dubious ass-covering.

Thursday’s White House meeting was one in a series of gatherings Biden is hosting as chair of a post-Newtown presidential task force on gun violence. Others may or may not have involved substantive discussion, but this one was evidently designed to placate people who are concerned about the effects of violent entertainment without actually broaching the topic. To go by the joint statement issued afterward by the showbiz bigwigs, it may have been the most guarded and noncommittal conversation in Washington history:

The entertainment community appreciates being included in the dialogue around the Administration’s efforts to confront the complex challenge of gun violence in America. This industry has a longstanding commitment to provide parents the tools necessary to make the right viewing decisions for their families. We welcome the opportunity to share that history and look forward to doing our part to seek meaningful solutions.

Maybe you read through all of that; I fell asleep right around “entertainment community,” which is one of those phrases that maxes out the meaninglessness meter. Let me be clear that I’m opposed to any form of censorship, and I believe the evidence suggesting a connection between fantasy violence on screen and violence in the real world is murky at best. You can cherry-pick social-science studies on all sides of this issue to support whatever conclusion you care to draw, and professional organizations like the American Psychological Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics have long made sweeping and possibly overstated claims about a clear correlation. But the best and simplest summary I have found comes from Texas A&M psychologist Christopher J. Ferguson: “If you are curious whether media violence contributes to violent crime, the simple answer to that is we really don’t know.”

Producers of movies, TV shows and video games feel understandably cautious about what they say in the wake of that spittle-flecked press conference by the verminous and turdlike Wayne LaPierre of the National Rifle Association, who sought once again to blame everything wrong in American life on Mortal Kombat and “Natural Born Killers.” (I cannot explain the cultural right’s fixation on that collaboration between Tarantino and Oliver Stone, a movie self-evidently intended to indict the media’s fascination with violence. Except to say that folks like LaPierre are more likely to have seen "Natural Born Killers" than, say, Michael Haneke’s “Funny Games” or Pasolini’s “Salò.”)

LaPierre is a dangerous and frightening idiot who has done immeasurable damage to the reputations of millions of responsible gun owners in this country. Yet the cultural unease he tried to tap into is one I share to some extent. Like so many other parents, I feel misgivings about the effects (whether measurable or not) of the ubiquitous media universe in general and ultraviolent entertainment in particular. You can’t blame anyone for suspecting that the profound bogosity of that non-statement I quoted above suggests that the “entertainment community” feels it has something to hide.

I especially love the first sentence of that press release, with its nebulous third-person address and its polite, mystified passive voice: This place is sure nice! Remind me again what we’re doing here? What Motion Picture Association of America head Chris Dodd (a former Senate colleague of Biden’s) and other industry spokesmen and lobbyists apparently expressed at the White House was their “longstanding commitment” to punting all questions of morality, decency and quality onto the shoulders of America’s overburdened parents. It’s not that I disagree with that position on any fundamental, philosophical level, I guess; it’s that behind that statement you can hear the grateful sighs as those guys washed their hands in the White House bathroom and accepted a hand towel from the attendant. I hope they got some neat little petits-fours with their coffee.

On the granular level of politics, you can understand why the reportedly cordial discussion at this meeting focused mainly on the entertainment industry’s widely ignored and notoriously arbitrary ratings systems. (Which, as Kirby Dick’s documentary “This Film Is Not Yet Rated” established, are far more tolerant of violence and teen-oriented raunch than of portrayals of consenting adult sexuality.) Media violence is supposed to be one of the subjects Biden addresses in his forthcoming report to President Obama, but since nobody can agree what the effects of media violence are, still less what to do about it, it’s easier to stick to meaningless symbolism. (Biden's entire task force is likely to be swallowed up in meaningless symbolism and miss a possible history-shaping moment, if you ask me. But that's a much bigger question.)

In one of those coincidences that’s not a coincidence at all, on the same morning of the White House meeting, Tarantino was losing his cool all over Krishnan Guru-Murthy of Britain’s Channel 4 News. (Video of the entire interview is embedded below.) In this case, the temporary deflection from meaninglessness was precisely the problem, as Guru-Murthy tried to push the director of “Django Unchained” (and the screenwriter of “Natural Born Killers”) outside the anodyne comfort zone of the movie-junket interview. As the nettled Tarantino himself said, “I’m here to sell my movie. This is a commercial for the movie, make no mistake.”

That moment of hip-hop-style candor might almost have been refreshing. But it was a whole lot less refreshing to see Tarantino acting so aggrieved about a journalist daring to ask him real questions, and it was downright shocking to see how unprepared he was to tackle an issue he’s had 20-odd years of writing and directing violent films to think about. Asked why he felt sure there was no connection between movie violence and real violence, Tarantino snapped: “Don’t ask me a question like that. I’m not gonna — I’m not biting. I refuse your question … I’m not your slave, and you’re not my master. You can’t make me dance to your tune. I’m not a monkey.”

I will leave it to Tarantino’s shrink to explore how and why these bizarre images of slavery and racism leaked out of “Django Unchained” and into his conversation with a British journalist of South Asian heritage. What’s more important is what he says next, after Guru-Murthy challenges his “commercial for the movie” remark. Asked whether he’s willing to talk about anything serious, Tarantino responds: “I don’t want to talk about what you want to talk about. I don’t want to talk about the implications of violence.”

This, unfortunately, is where Tarantino’s video faux-pas and Chris Dodd’s ultra-careful press release overlap: They don’t want to talk about the implications of media violence. Or rather, they’re so sure that there are no serious implications that they’ll sound panicky and out of control (in Tarantino’s case) or like a mealy-mouthed sycophant who’s covering for the makers and sellers of mendacious crap (in Dodd’s).

Let me back up and repeat that I do not believe that media violence plays a significant or determining role in real-life outbreaks of violence. “The Dark Knight Rises” did not cause the Aurora, Colo., massacre, and video games didn’t cause the one in Newtown. Spectacular gun violence of that variety is almost exclusively an American problem (and a male American problem, at that). I've said this before: Japan and South Korea, to cite the obvious examples, have some of the craziest and most violent pop culture you can imagine, yet those countries are probably the least violent societies in modern history.

The most anyone can say after all the years that social scientists have studied this question, as Paul Waldman writes in the American Prospect, is that “media violence can make some people more aggressive in some ways to some degree in some situations for some period of time.” Even that may be putting the case too strongly, and it avoids the question of how much connection there is between the ambiguous category of “aggression” and actual violence.

Christopher Ferguson, the Texas A&M psychologist I quoted earlier, has suggested that media violence does not cause or stimulate violent crime but “may act as a stylistic catalyst,” inspiring people who are predisposed to violence to imitate scenarios they’ve seen in movies or on TV. That fits my empirical and unscientific understanding of human nature, as does the idea that our media-driven society – the “Society of the Spectacle,” in philosopher Guy Debord’s phrase – can have a deadening or dehumanizing effect on individuals that has little to do with content or subject matter.

Issues like poverty, family violence, mental illness and the easy availability of high-powered firearms – the elephant in the room that Wayne LaPierre hopes to obscure with his rabid foaming – have a hell of a lot more to do with America’s gun violence than whatever marginal, incremental effect violent entertainment may have on disturbed people. I know that. But I also know that refusing to talk about the cultural dimensions of the problem is a grave mistake, one that misunderstands or misstates the authentic social role of the artist. In different ways, Dodd and Tarantino are pretending that art and entertainment do not matter and have no consequences, that they’re meaningless diversions rather than mirrors that can reflect or distort the soul of a troubled society. If Dodd is a politician accustomed to lying, Tarantino should know better (and he used to).

If the consumption of media is even 1 percent of the problem (or 0.1 percent, or less than that), it’s better to face that possibility directly than to sweep it under the carpet in the name of political convenience. We have more than enough convenient mendacity in the public life of this country – just look at LaPierre. To talk in the passive voice about the entertainment community and its longstanding commitments, while feigning ignorance about the widespread perception that Hollywood is part of the problem -- or to tell an interviewer who dares to ask tough questions “I’m shutting your butt down” -- only empowers the enemies of culture and adds to the rising tide of bullshit.

Shares