Scientists have expressed anger and doubt over a Chinese geneticist’s claim to have edited the genes of twin girls before birth, as government agencies ordered investigations into the experiment.

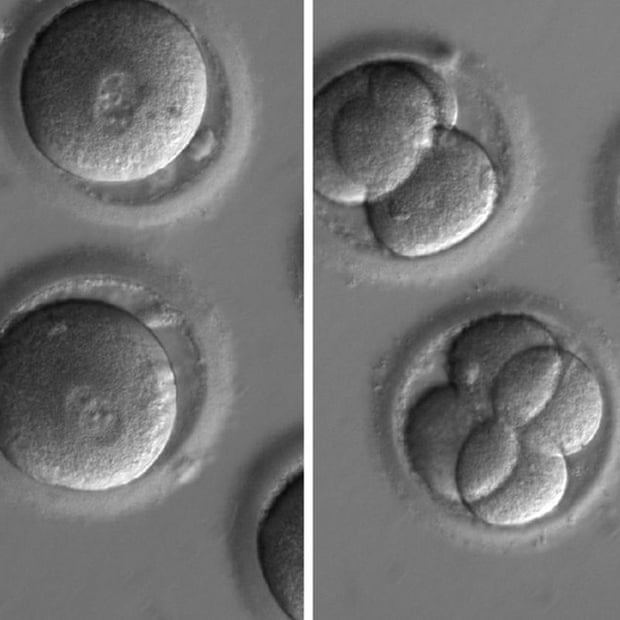

A global outcry started after the genetic scientist He Jiankui claimed in a video posted on YouTube on Monday that he had used the gene-editing tool Crispr-Cas9 to modify a particular gene in two embryos before they were placed in their mother’s womb.

He said the genomes had been altered to disable a gene known as CCR5, blocking the pathway used by the HIV virus to enter cells.

Some scientists at the International Summit on Human Genome Editing, which began on Tuesday in Hong Kong, said they were appalled the scientist had announced his work without following scientific protocols, including publishing his findings in a peer-reviewed journal. Others cited the ethical problems raised by creating essentially enhanced humans.

Qiu Renzong, a bioethicist and emeritus professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Science in Beijing, said He’s decision to work outside established and supervised scientific protocols could taint the reputation of Chinese science.

“Of course it’s not ethical,” said Qiu, after publicly criticising He’s work before the several hundred people in attendance. Qiu said He’s university, the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, had rejected his request to perform the experiment. That led the Stanford-educated He to find a private hospital outside the academic system to apply his research. “Clearly it is a fraud,” said Qiu. “Maybe he fabricated a form, and found people to sign it.”

Q&AWhat is Crispr?

Show

Crispr, or to give it its full name, Crispr-Cas9, allows scientists to precisely target and edit pieces of the genome. Crispr is a guide molecule made of RNA, that allows a specific site of interest on the DNA double helix to be targeted. The RNA molecule is attached to a bacterial enzyme called Cas9 that works like a pair of 'molecular scissors' to cut the DNA at the exact point required. This allows scientists to cut, paste and delete individual letters of genetic code.

In October 2020, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A Doudna were awarded the Nobel chemistry prize for their work on it – the first time that two women have shared the prize.

China’s National Health Commission has ordered officials to investigate and verify He’s claims. In addition, the Health and Family Planning Commission in Shenzhen, where the scientist worked, said it was exploring the ethical questions as it reviewed the process followed in He’s work.

Feng Zhang, a molecular biologist at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of the inventors of the Crispr technology, called for the results to be made public so the science community could examine He’s work.

“I don’t think it was handled in a transparent way. Particularly since the first time I heard about it was by reading it in the newspaper,” Zhang said. “And I think transparency is incredibly important. Especially for new experimental treatments.”

If He’s claims are true, the twins would pass the altered DNA on to any offspring they have, which several scientists said would create a host of ethical and medical problems.

“It’s something that will have consequences in our life,” said Mohammed Ghaly, a professor of Islam and biomedical ethics at Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Doha, Qatar. “We end up with big ethical questions … the decision that was made about these twin girls was not made by them, but by someone else. The changes that happened to them will remain in their offspring for future generations.

“Are we, as humans, in the position to make such decisions with long-term impact that go beyond our lives and our grandchildren?”

Some scientists were cautious about denouncing He and his work without knowing more details. “Fundamentally, there’s nothing different in making [genome] edits in adult humans versus the embryo,” said one conference attendee, Eben Kirksey, an associate professor of anthropology at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

But Kirksey agreed it raised difficult ethical questions. “It risks creating a new, genetically modified elite … who can’t get sick but pass it on to other people.”