Anna Jones* was 16 years old the day she walked into her mother's bathroom and told her she was leaving. Her mother leapt out of the shower and chased Anna down the hall until the two met at a standstill — her mom at the top of the stairs, Anna at the bottom. "You can't leave," her mother yelled. "I'm calling the police!"

"What are you going to tell them?" Anna fired back. "That I'm being kidnapped by my husband?"

Just the day before, her mother had walked her and Tim*, then 30, into City Hall and gave permission for the couple to get married. Their agreement, though, had been that Anna would finish her sophomore year of high school living with her mother, and then move in with Tim the following summer.

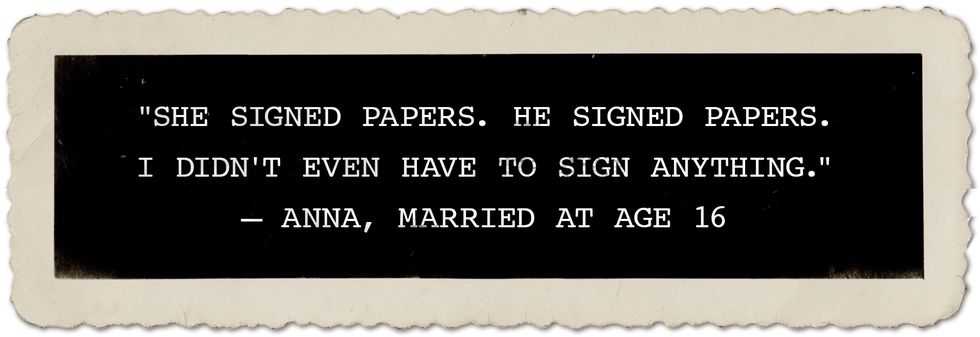

But now that they were married, there was little her mom could do. "She signed papers. He signed papers," says Anna, now 32. "I didn't even have to sign anything."

Anna had met Tim, then 29, at a behavioral healthcare facility, where he was a mental health technician. She was a patient in the adolescent girls' unit.

Her childhood had been a rocky one from the start. "My mother was 45 when she found out she was pregnant with me, and I was an unwanted pregnancy from the get-go," she says. Her father was on the road all the time as a truck driver. When Anna was 12 years old, she learned that her father had advanced lung cancer, and his doctors had given him months to live. In the eight months he survived past his diagnosis, she grew up fast. "I'd have to mash up his food, feed him and change his Depends," she recalls. "It was a heavy weight for me at that age, and it created a lot of animosity toward my mother."

Her father passed away when she was 13, and the death prompted Anna's mother to pack up and move, leaving her to finish 8th grade in a new school where she knew no one.

"I would yell at her non-stop," admits Anna. "I had gotten out of control to the point where she had no clue how to deal with me."

So her mother took her to a nearby long-term facility, where her behavior turned around immediately. Anna was a model patient and had full access to the hospital floors as long as she told one of her supervisors where she was going. Eventually, she met Tim.

Tim started flirting with Anna in small, inconspicuous ways. "I would have to put a check mark beside my name on the dry erase board to indicate that I was going to the cafeteria or whatever, and he would come up and erase my check mark and wink at me," she says. "So I'd have to go put my mark back."

Then Tim started slipping her unsolicited notes, which gradually escalated. By the time Anna was about to be discharged from the facility, the notes would say things like, "What is it going to take for me to be able to let you go?" and "I don't think I'm going to be able to live without seeing you again."

On her first day home, she saw on her caller ID that she had a missed call from the facility. Tim tried again the next day, and that time she was able to pick up. Their relationship developed through phone conversations, then progressed to visits on weekends. About once a month, Tim spent the night with Anna at her mother's house. Occasionally, Tim acknowledged their age 15-year difference — but always in a way that framed their relationship as "different." She was "special," and that made the fact that he was dating her OK. "And I believed all that because here's this person who is expressing love to me," Anna says. "I'd never had that before."

In the years that followed, it was as if her mother had a new daughter. Anna was focused in school, and they didn't fight. So, about four months after her 16th birthday, when she asked her mother if she and Tim could get married. Her mother said yes. They hashed out a deal — Anna would finish her sophomore year of high school at home, and then move in with Tim the following summer. But he had other ideas in mind. He helped her pack up her things after they returned from their wedding ceremony, and together they decided she would tell her mother she was leaving the next morning when she was in the shower, where it would be difficult for her to react quickly. The result was exactly as they had hoped — the standstill, where Anna reminded her mother that her husband could not kidnap his own wife.

THE BIGGER PICTURE

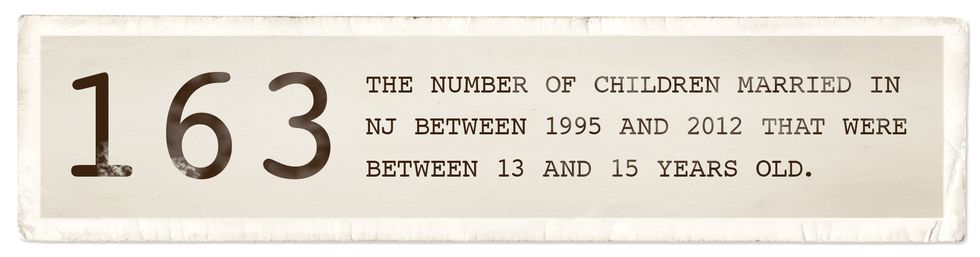

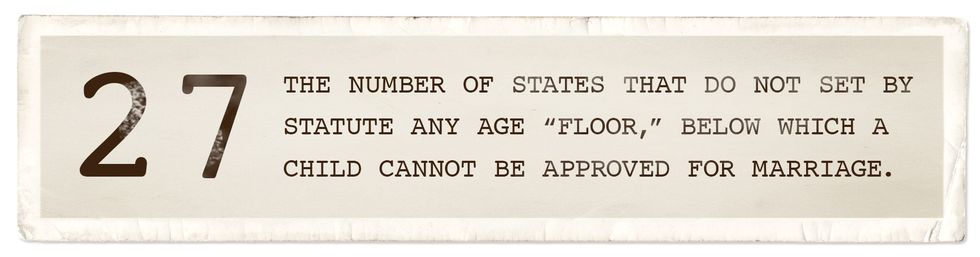

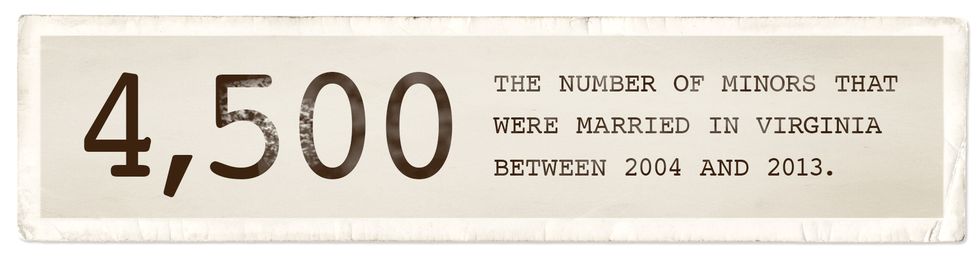

Most Americans know that it's illegal to get married in the U.S. if you're under the age of 18. What most people don't know is that there are loopholes. The most common one is parental consent, as was the case in Anna's situation. Currently, 27 states do not set by statute any age "floor" below which a child cannot be approved for marriage, as long as they have parental consent and/or the approval of a judge and meet any other criteria. Those states include Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. And there are 38 states plus Washington, D.C. in which older minors (ages 16 and 17) can be approved by a clerk — without having to go before a judge — to marry someone above the age of 18. Some of the most shocking numbers occur in states such as New Jersey, where 4,000 children were married between 1995 and 2012, 163 of which were between 10 and 15 years old. In Virginia, nearly 4,500 people under the age of 18 were married between 2004 and 2013. Nearly 90% of those marriages involved an adult spouse.

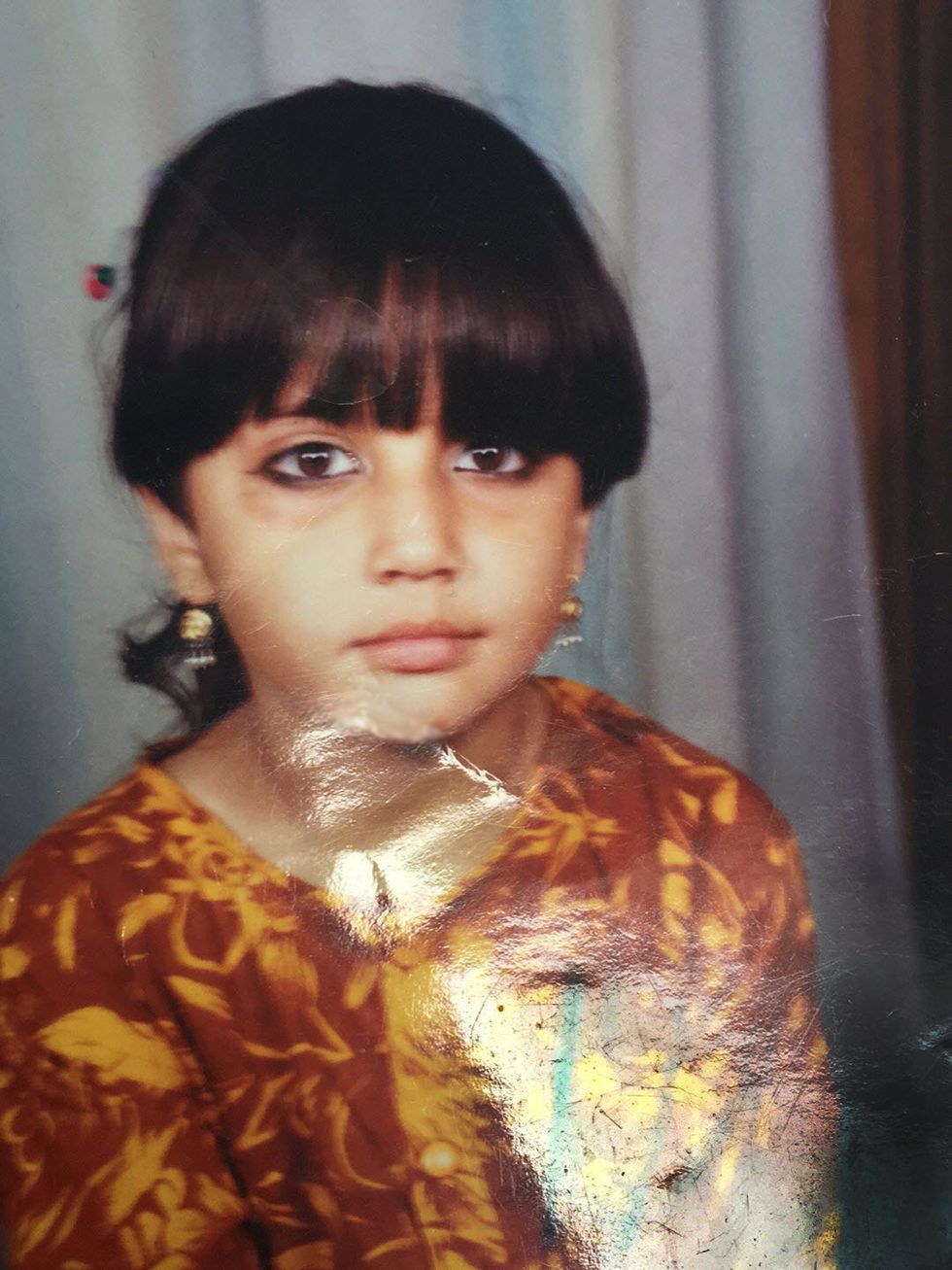

One child forced to marry an adult was Naila Amin. She has lived in the United States since the age of 4, when she moved from Pakistan to Queens, New York, with her parents.

She excelled in school, despite relentless bullying for the way she looked. "People used to call me Hindu because we wore Pakistani clothes," says Naila, 26. "We were the only Pakistanis on the block."

Amin says she "blossomed" in 7th grade, when she started getting attention from boys. Like most young girls, the attention was exciting, until she remembered that she was technically already spoken for. "I was promised off at the age of 8," she says. Her dad had arranged for her to marry her then 28-year-old cousin back in Pakistan.

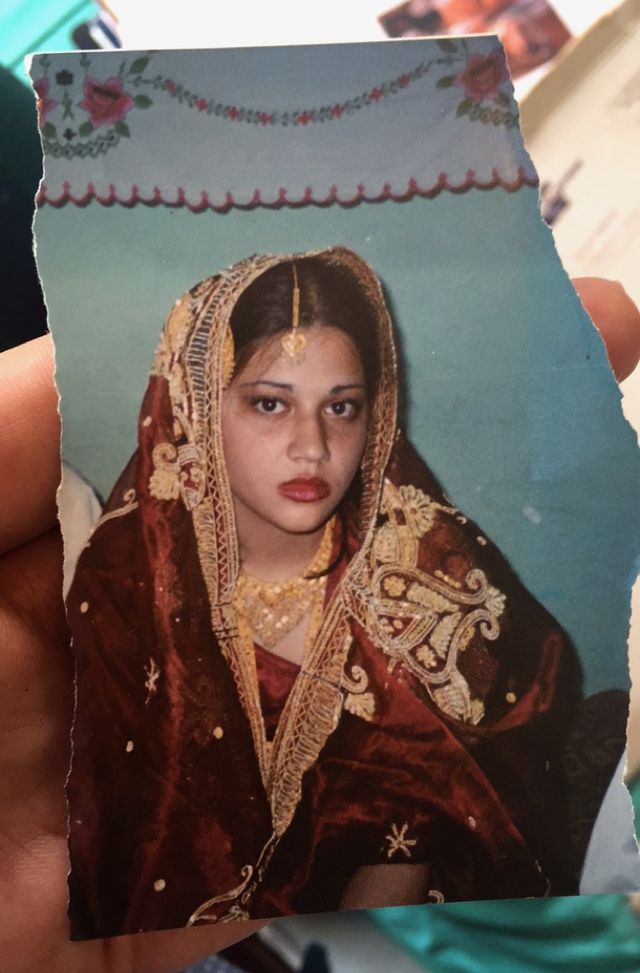

"The whole point was for him to be able to come to America," she explains. "It was basically immigration fraud." When Amin was 13, she skipped her 8th grade year to go to Pakistan with her parents. While there, Amin's family dressed her up as a bride, and she and her cousin signed a Nikah, an Islamic marriage contract.

Eventually, Amin was able to return to the U.S. for a time and even started dating someone at school. But once her father found out that she had a boyfriend, he decided it was best for her to live in Pakistan until she turned 18.

So, on January 5, 2005, when Amin was only 15, a second ceremony was performed and she was forced to go live with her husband. There, she was essentially a prisoner in her own home. "[My ex-husband] took my favorite cassette away with an Indian song I used to listen to — it basically translated into, 'I am going to be who I am, no matter what, you can't change me.'" He also took her cell phone and her passport; she wasn't allowed to pick up the house phone.

When Amin is asked to describe what being married as a child was like, she boils it down neatly: "Imagine an ex-boyfriend that you really, really hate. You don't want him touching your body. It was like living with my enemy, cooking for my enemy, sleeping with my enemy."

Amin refused to have sex with her husband, and after 10 days living under his roof, she tried to run away. When she returned, she was beaten in front of 30 people, including her family and his.

"He pulled me from my hair from one side of the house to the other," she says. "He was whipping me with an electric cable, kicking me in the head. I never thought I could see stars, the ones they show in the cartoons, but I saw stars that day."

Later that evening, once the crowds disappeared, Naila was raped by her husband.

She was, in every sense of the word, trapped. Many of the resources that are available to adults in abusive marriages aren't available to married minors. In the United States, a person cannot just remove the child from the situation — that could be considered kidnapping, punishable by up to life in prison. Child Protection Services also typically declines to get involved before a child is married, and after the marriage, they may no longer even have the authority to get involved. Often, the State Department faces legal and practical limitations to their ability to help an American who is legally married in another country.

"The sad truth is, when a child calls for help, there's very rarely a positive outcome," says Fraidy Reiss, founder of Unchained at Last, a New Jersey-based non-profit that fights against forced and child marriage in the U.S. Reiss also survived an abusive forced marriage of her own, saving money in a cereal box over the course of five years before she was finally able to escape at the age of 32. "They often give up and decide to go with the marriage, and many turn to self-harm or suicide attempts."

Amin says she tried to kill herself a few times. "Over there [in Pakistan], they have pesticide pills. Whoever wants to kill themselves, that's how they do it," she explains. "I asked one of my little cousins, 'Can you go get me some pesticide pills?' And I don't know why but that 10-year-old boy told on me, and I ended up getting a beating instead."

BOUND TO A STRANGER

To move in with Tim, Anna Jones had to drop out of school. When she tried to re-enroll in high school in her new town, however, she found that her hands were tied. "They assumed I was pregnant, and when I told them I wasn't, they said that it was bound to happen, and they just couldn't have that at their school," Jones says. She tried calling her old school for her transcripts to apply for a GED, but because they still considered her a minor, she needed a parent's permission — and she and her mother weren't speaking.

Unable to continue her education, Jones took a minimum wage job at a local grocery store to make ends meet. Tim had quit his job by this point and was spending his days at home drinking, she says. One night, when a co-worker paid for her meal at a work event, Tim became so angry he staged a suicide attempt. "He had a half-empty bottle of Southern Comfort beside him and a bunch of Tylenol PM scattered across the floor," she says. "It went from being 'I'm so special and that he and I belong together' to 'Look at how I'd hurt him.'"

Things took a turn for the worst on her 18th birthday. By this point, Jones was pregnant. Well into her second trimester, her husband took her to a local strip club to celebrate and bought her a lap dance. "I was petrified and humiliated," she says.

He grew more and more violent, pinning Jones to the wall or holding her hands behind her back during his drunken rages. But one night, he knocked his wife to the floor and wrapped his hands around her throat, choking her. "I really thought he was going to kill me," Jones says. Her daughter, still only a baby, was on the floor watching her parents. "She started laughing, because of course she has no clue what's going on — in her mind mommy and daddy are wrestling," Jones says.

That's when it hit Jones that she needed to get out of her marriage. "It was a huge wake up call for me, realizing that things were going to get a lot worse and she'd grow up thinking that was OK."

Jones told her husband that she wanted a divorce. He agreed, but it would mean losing her baby girl; he wanted full custody. "He conditioned me to think that I wasn't capable to care for my daughter — that I was an ex-mental health patient and other things that he held over my head," she says. She agreed, a decision she regrets today. "The ultimate victim in all of this is my daughter," Jones says, "because she has grown up feeling like her mother totally abandoned her."

Jones has since gone on to earn her GED and wants to get her master's degree in social work. She says maintaining a relationship with her daughter is still difficult because of her custody arrangement, but she refuses to press charges against her ex-husband in order to see her more often. "If did then I would lose her forever," she says. "She would completely hate me."

A BONDED CHOICE

Stories like Naila Amin's and Anna Jones's don't come from a void: Even in 2016, there are groups entirely dedicated to the marriage of youth. Earlier this year, a organization called Let Them Marry, a ministry dedicated to facilitating young fruitful marriages, attempted to organize a "Get Them Married" retreat at a campsite hosted by the Salvation Army in Wichita, Kansas. While the group adamantly denies supporting child or forced marriage, families were encouraged to connect in the hopes of arranging unions between their children.

Once the Salvation Army discovered the intentions of the retreat, they told Let Them Marry that they were not welcome at their campsite. "We firmly believe the activities promoted by Let Them Marry breaches our Safe from Harm guidelines put in place to protect children," says Major Joseph Wheeler, Wichita City Commander for the Salvation Army.

Groups like Let The Marry believe that young marriage will lead to reproduction during peak childbearing years. Planned or unplanned, teen pregnancy has historically been a reason why parents marry off underage children — often with dire results. "Teen mothers who marry end up having more children earlier and more closely spaced," says Jeanne Smoot, senior counsel for policy and strategy at the Tahirih Justice Center, which offers pro bono legal services and other aid to women and girls in dangerous situations. She also notes that there's a 50% dropout rate from high school and they're 31% more likely to live in poverty.

Although marrying young has been common at different points in history, it can have devastating lifelong effects. "A parent may have the intention to provide security and stability by forcing a marriage," says Smoot. "But the odds are that they will set their child up for failure instead and for lifelong harm."

A decade after being pressured into marriage by her parents, Nina Van Harn realized there was something wrong the day her son ran up to her and handed her a dandelion. She acted excited and said, "Thank you so much!" When he walked away to play, though, she thought, I don't feel anything.

"I reacted how I thought I should," she says, "but I asked myself, Why don't I feel excited by this? And I realized, I'd shut down so much that I stopped feeling joy."

Van Harn grew up in a conservative Baptist community in Michigan. She and her three siblings, two sisters and a brother, were homeschooled, and the girls started wearing long skirts that covered their knees.

The first time Van Harn's father tried to marry her off to a young man in their community, she had just turned 18. "I was writing all of this stuff down in my journal — Am I worthy? Is he going to like me?" she says. "But I never once asked the question, Am I going to like him?"

That boy later decided he didn't want to pursue the courtship, but her father tried again when Van Harn turned 19. One day, her father told her that she needed to be home by 9:30 p.m., when she'd be receiving a phone call from her new suitor.

The call was as awkward as one would imagine. They asked each other about favorite colors, what they liked to do for fun, and quickly discovered they had nothing in common. He was very into sports and otherwise a homebody. She had dreams of traveling the world. After a couple more calls, Van Harn was given a week to decide if she wanted to take the next step — marriage.

She said yes. "I was being faced with being shunned by God and by my family, so I thought it was probably a good idea to accept this arrangement," she says. Later, Van Harn learned the meaning of a bonded choice: "When they give you two choices, and one has serious repercussions and the other one has praise, that's not actually a choice."

Van Harn wanted a spring wedding, but her father told her she couldn't make her fiancé wait that long. They booked the first available date at the church — just three months away.

Looking back at her wedding, Van Harn calls herself complacent: "I had pretty much resigned myself to the idea," she says. "In my journal, I wrote, This is me giving up on all of my dreams."

Three months into her marriage, Van Harn was pregnant. What followed, she says, "was 11 years, three children, and living this scripted lifestyle and not knowing why I was so miserable."

PLANNING AN ESCAPE

People who are desperately trying to escape forced or child marriage have few resources, but one of them is the aforementioned Tahirih Justice Center. For adults, the center will work with local shelters and law enforcement if the person just needs a safe place to stay for a night to gather their thoughts and figure out next steps.

The hardest pills to swallow, says Casey Carter Swegman, Tahirih's project manager of the Forced Marriage Initiative, are the phone calls she's gotten from young girls in high school. "This is a real phone call that I've received on more than one occasion," she says, where in between classes, a minor is borrowing a friend's cell phone and quickly trying to explain her situation. By now, Swegman knows she doesn't have much time and rapid-fires one or two pieces of advice — that no one has the right to force them into marriage, that they have the right to say no and that the Tahirih Justice Center is there to help them. If Swegman is lucky, she is able to get through all of this before she hears someone yell in the background that cell phones aren't allowed in the hallway.

"And I never hear from that person again," says Swegman. "For every one of those phone calls, I can only imagine how many girls don't even have that one friend whose cell phone they can borrow."

Naila Amin finally got a break one evening when she and her husband were having dinner at her grandmother's house in Pakistan. Her mother's cousin handed her a cell phone and told her to "go upstairs and use the bathroom." She left a message with Deborah White, her Child Protective Services case worker back in the United States. Amin had known White for years — from the age of 10, she was put into the CPS system and lived in foster homes on multiple occasions.

A month went by without hearing anything from White, and Amin's hopes started to wear thin. What she didn't know was that White was climbing through hoops with the State Department, the U.S. embassy in Pakistan and Congress to get Amin home safely.

Finally, in March 2005, Amin received a call from her father. Amin had been taken out of the country by her parents when she still technically belonged to the foster care system, and therefore needed to return home immediately. "He told my husband that basically, in America, if you don't go to school they report you to Child Protective Services," she says. Thus, she had a ticket out of Pakistan.

During the cab ride to the airport, Amin's husband was feeling up her chest. "I was like, he needs to get his measly little hands off of me because I want to chop them off," she says. As soon as she walked through the security doors, Amin says she felt relieved, and her body was coming down from such shock that she developed a fever on the plane. "I remember the flight attendant giving me Advil — I think my body knew that the ordeal, the hell, was over."

When her plane landed at JFK, the pilot made an announcement to all passengers. "He said, 'Everyone stay seated until Miss Naila gets off.'" When the doors opened, Amin was greeted by about 20 people who had worked around the clock to bring her home, including social workers and detectives.

She spent her first night back in the U.S. at the psych ward of Nassau University Medical Center in East Meadow, New York. Afterward, she eventually settled back in with her parents, where she still lives today so that she can save up enough money to live with her boyfriend and their 9-year-old son. She hopes to earn her master's degree in social work, like Anna Jones. "I love my parents," she says, "but I want to love them from afar."

GETTING OUT

As the years dragged on, Nina Van Harn grew more and more lethargic and depressed. She became too tired to have sex, so her ex would "pester until I gave in," she says. "I'd think, Fine, I'm just going to lay here and try to fall asleep, and then I'd wake up and wonder why I felt so worthless." Eventually, she was able to find a therapist to help.

"She was a godsend," says Van Harn. "She started to help me see that what was going on was abuse. In our circle, abuse is a black eye and a broken leg. It's not verbal. It's not emotional. And there's no such thing as assault or rape in a marriage."

Then one afternoon when she showed up to a friend's house to pick up her kids after a therapy session, her friend noticed asked her if everything was OK — and offered Van Harn a place to stay. "I just broke down and said, 'I'm not in a good place.'"

On September 24, 2014, her children's father left for work, and, once his car was out of the driveway, Van Harn started packing like mad. The same friend who watched her kids during therapy came down to help Van Harn pack up the car. Once she crossed the Indiana-to-Michigan boarder, Van Harn texted her mom to let her know that she'd left. "Everything is going to be OK. I love you," she wrote. Her mother responded saying that she loved her too.

After a two-year battle, on September 6, 2016, Van Harn was finally granted an annulment. The biggest thing she deals with now is the slander from her old community.

"I started having friends and people calling me, asking what was I thinking," she says. "And I heard a lot of rumors that were going around, that I'd become a partier, that I was sleeping around, that I was leaving the kids with strangers in order to date. You name it, they were throwing it at me."

Despite that, she and her three children are safely living in Michigan: "Although it was a long battle, it was worth it."

All three women are working in various ways to end child marriage in the U.S. Both Naila Amin and Anna Jones have worked on advocacy projects with the United Nations, and Amin has launched a GoFundMe page to raise money for the Naila Amin Foundation, which she hopes to use to open the first group home for minor girls escaping forced marriages. In July, the state of Virginia enacted new legislation, making it illegal for anyone under age 18 to get married, with an exception only for 16-17 year olds who have been emancipated (declared legal adults) after a special court proceeding. The hope is that other states will follow suit, banning marriage for all minors without exceptions.

"I'm very behind on everything in life because of what happened to me — I'll be 27 in October and haven't even passed the test to get a driver's license," Amin says. "Why in the world is this allowed? Something's got to change."

*Names have been changed for the protection of some sources.

If you're facing a forced marriage or know someone who has been affected by forced marriage, you can contact Tahirih's Forced Marriage Initiative (FMI@tahirih.org / 571-282-6161) or Unchained at Last (908-481-HOPE) for help.