OK, let’s take him.” Within seconds two officers grabbed me, each seizing an arm, and shoved me against the drinks machine that rested along the front wall of the McDonald’s where I had been eating and working on my report. As I released my clenched hands, my mobile phone and notebook fell to the tiled floor. Then came the sharp sting of the plastic cable tie as it was sealed, pinching tight at the corners of my wrists. I’d never been arrested before, and this wasn’t quite how I’d imagined it would go down.

Two days earlier, I’d been sent to Ferguson, Missouri, by the Washington Post, to cover the aftermath of the police shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black 18-year-old. The fatal gunshots, fired by a white police officer, Darren Wilson, on 9 August 2014, were followed by bursts of anger, in the form of protests and riots. Hundreds, and then thousands, of local residents had flooded the streets. For the Ferguson press corps – which would eventually swell from dozens of reporters for local St Louis outlets into hundreds of journalists from farther afield, including dozens of foreign countries – the McDonald’s on West Florissant Avenue became the newsroom.

Because the protests were largely, in those first days, organic and not called by any specific group or set of activists, they were also unpredictable. Some of the demonstrators came to demand an immediate indictment of the officer. Others wanted officials to explain what had happened that day, to tell them who this officer was and why this young man was dead. Scores more stood on pavements and street corners unable to articulate their exact demands – they just knew they wanted justice. Covering Ferguson directly after the killing of Mike Brown involved hours on the streets, with clusters of reporters staked out from the early afternoon into the early hours of the morning. At any point a resident or a group of them could begin a heated argument with the police or a reporter. A demonstration that had for hours consisted of a group of local women standing and chanting on a street corner would suddenly evolve into a chain of bodies blocking traffic, or an impromptu march to the other side of town.

It wasn’t much later that the riot-gear-clad officers entered the McDonald’s, suggesting we all leave because, with protests still simmering outside, things could get dangerous once the sun went down. Then, when it became clear that we were happy to wait and see how things developed outside, they changed their tune. Now the officers were demanding we leave. When I didn’t move fast enough, they grabbed me.

I was led out of the restaurant to wait for transport to police headquarters, with Ryan Reilly of the Huffington Post, who had also been arrested. We were driven across town in a police vehicle also containing a local minister, still in her clerical collar, who sang hymns for the entire journey.

The officer who arrested us had told us, smirking, that we’d be spending the night in the cells, but he was wrong. They locked us in a cell, but about half an hour later, we were turned loose. Inundated with phone calls from other reporters and media outlets, police chief Thomas Jackson had given orders for us to be released. By the time we were given back our belongings – unlaced shoes, notebooks, phones – we’d become momentary media celebrities.

I’d arrived in Ferguson thinking I’d be there for just a couple of days. I’d write a feature or two, and then I’d go back to DC and get on with writing about politics. But it became clear that I wasn’t escaping Ferguson any time soon.

More than 150 people were taken into custody by the Ferguson and St Louis County police departments in the week-and-a-half that followed Mike Brown’s death, the vast majority for “failure to disperse” charges that came as a result of acts of peaceful protest. I was the first journalist to end up in cuffs while covering the unrest.

Resident after resident had told stories of being profiled, of feeling harassed. These protests, they insisted, were not just about Mike Brown. What was clear, from the first day, was that residents of Ferguson, and all who had travelled there to join them, had no trust in, and virtually no relationship with, the police. The police, in turn, seemed to exhibit next to no humanity towards the residents they were charged with protecting.

What happened in Ferguson would give birth to a movement and set the nation on course for an ongoing public hearing on race that stretched far past the killing of unarmed residents – from daily policing to Confederate imagery to respectability politics to cultural appropriation. The social justice movement spawned from Mike Brown’s blood would force city after city to grapple with its own fraught histories of race and policing. As protests propelled by tweets and hashtags spread under the banner of Black Lives Matter and with mobile phone and body camera video shining new light on the way police interact with minority communities, America was forced to consider that not everyone marching in the streets could be wrong. Even if you believe Mike Brown’s own questionable choices sealed his fate, did Eric Garner, John Crawford, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, and Sandra Bland all deserve to die?

Ferguson would mark the arrival on the national stage of a new generation of black political activists – young leaders whose parents and grandparents had been born as recently as the 1970s and 1980s, an era many considered to be post-civil rights. Their parents’ parents had been largely focused on winning the opportunity to participate in the political process and gaining access to the protections promised them as citizens. Their parents focused on using the newfound opportunities and safeties provided by the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts to claim seats at the table, with political and activist strategies often focused on registering as many black voters and electing as many black leaders to public office as possible. For at least two decades, the days of taking the struggle to the streets had seemed, to many politically active black Americans, a thing of the past.

The shooting of Mike Brown had happened on a quiet side street, in a spot surrounded by four-storey apartment buildings. As the crowds gathered, others took to windows and porches, looking down at the chaos developing below. Within minutes of the shooting, word spread through the surrounding apartments, and beyond, that Brown’s hands were up in the air when he was shot. Darren Wilson had encountered Brown and his friend Dorian Johnson while responding to a call about two young men, matching their description, who had just been involved in the robbery of a nearby off-licence.

People in Ferguson did not know whether Brown was attempting to surrender or attempting to attack Wilson when the officer shot him. They did know that the police in Ferguson looked nothing like them: an almost all-white force charged with serving and protecting a majority black city. They knew all too well about the near-constant traffic tickets they were being given, and how often those tickets turned into warrants. And they knew that Mike Mike (as the family called him), the quiet kid who got his hair cut up the street on West Florissant and who was often seen walking around in this neighbourhood, was dead.

Mike Brown’s body remained on the hot August ground – a gruesome, dehumanising spectacle that further traumatised the residents of Canfield Drive and would later be cited by local police officials as among their major mistakes.

The Ferguson and St Louis County police had sent scores of officers, some in full riot gear and tactical vehicles, to deal with the growing crowds and to hold them back as they attempted to investigate the scene of the shooting for themselves. All of this is pretty standard for the scene of a police shooting – police, protesters, angered residents and families – but the scale of the immediate response from both the community and law enforcement signalled that Ferguson would be different.

And then, four-and-a-half hours after the shooting, officers finally removed Brown’s body from the asphalt. They did not address the crowds who needed answers after spending most of their Saturday hearing inflammatory rumours.

As the police began to leave, church groups started walking down Canfield Drive, following Brown’s mother, Lezley McSpadden, who was crying hysterically, to the spot where his blood stained the ground. When they arrived, the groups circled around McSpadden and her husband and began to pray, sing and hug. Some were older folks from the church up the road, others were younger residents who poured out of the Canfield apartments. What had been a rambunctious crowd had composed itself to create a vigil for a violent death.

But the tranquillity didn’t last. As the prayer group began to break up, the residents of Canfield began to yell. Prayer wasn’t going to fix this. Neither was singing. The police had to answer for this. Why was Mike Brown dead? Why had his body been left out for so long? And when would we get answers? Amid the shouting, someone lit a skip on fire. While moments earlier prayers were being sent up, now it was the flash of flames floating into the night air.

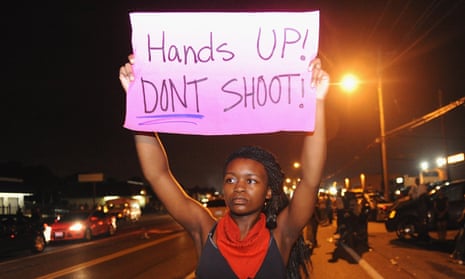

The following day, the Ferguson police department still hadn’t explained what had happened or apologised for keeping Brown’s body out on the ground for so long. And church groups were calling for a march in the dead teen’s honour. After Sunday services concluded, local pastors and their congregations met at the spot where Brown was killed. Hundreds showed up, and started marching and chanting what they believed to be Michael Brown’s own words in his final moments.

“Hands up, don’t shoot!”

The cries rang into the air as the crowd, including many students set to begin school the following week, as well as middle-aged residents of the apartment complex, moved forward. As they hit West Florissant and turned left, they were met by a wall of police officers. What had begun as a peaceful march became a heated standoff, blocking traffic in both directions. The crowd continued shouting at the officers, who were shouting back. And as the church groups began to leave, young men emerged who seemed angrier and more determined to extract revenge for Mike Brown’s death.

That night, armed vandals took advantage of raging protests to break into the QuikTrip petrol station just a block away from where Brown was killed, grabbing bags of crisps and sodas, cigarettes and lighters, as others ripped the ATM machine from the wall. Before long, the store was ablaze.

Photos and videos from the day of Brown’s death had gone viral, but it was the destruction of the QuikTrip, not the police shooting of Mike Brown, that brought the national media’s focus to Ferguson. Unrest had now become a riot. Yet another police shooting in a working-class black neighbourhood, even the breaking of a young black body left on public display, didn’t catch the attention of the national media. It was the community’s enraged response – broken windows and shattered storefronts – that drew the eyes of the nation.

By the time a grand jury concluded on 24 November 2014 that there was not enough evidence to charge Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson with a crime in the killing of Mike Brown, I had been in that city for the better part of three months. I would spend the next eight months crisscrossing the country, visiting city after city to report on and understand the social movement that vowed to awaken a sleeping nation and insisted it begin to truly value black life. Each day, it seemed, there was another shooting. In city after city, I found officers whose actions were at worst criminal and at best lacked racial sensitivity, and black and brown bodies disproportionately gunned down by those sworn to serve and protect.

Meanwhile, the protests had created a countermovement of scepticism, anger and hate, driven by some who genuinely believed that the coverage of Ferguson was overblown and amplified by others with more sinister motivations. These legions of sceptics insisted that the entire story was a fraud, that Mike Brown had deserved his fate, and that tensions in Ferguson were completely stoked by the media – based not on historical injustice, but on real-time race-baiting. The photos and videos that we had posted from the protests had unnecessarily fanned the flames, these critics insisted. And by demanding answers of the Ferguson police department, by wanting to know why this young man had died, the critics declared, we were now responsible for the social unrest in the streets.

On the afternoon of 22 November 2014, two days before the grand jury’s decision not to prosecute the officer who shot Michael Brown, Cleveland police officer Timothy Loehmann and his partner, officer Frank Garmback, responded to a call about a man with a gun outside a recreation centre. The man who called the police told the dispatcher that the person was possibly a child playing with a toy, information that was never given to Loehmann and Garmback. The officers believed they were responding to an active shooter.

Loehmann and Garmback pulled up in their cruiser next to a park gazebo where for the last hour 12-year-old Tamir Rice had been throwing snowballs and pretending to fire the toy weapon. Their cruiser slid on the snow-covered grass as Loehmann leaped out from the passenger-side door.

Loehmann claimed he yelled for the boy to show his hands, but that instead of complying, the boy lifted his shirt and reached into his waistband. Loehmann said that when he saw Tamir’s elbow moving upwards and the weapon coming up out of his pants, he fired two shots. Video of the shooting showed that less than two seconds passed after the officers arrived before one of them shot Tamir dead.

“At its core, Tamir’s death is a tale of stunning systemic police incompetence and indifference,” wrote Phillip Morris, the sole black metro columnist at the Cleveland Plain Dealer. It had been revealed that Cleveland police had hired Loehmann, the officer who shot Rice, without checking his references or running a serious background check. Had the city done that, they would have uncovered job reviews from his former supervisor which made it clear he would not recommend that Loehmann, the son of a police officer, be given a badge and a gun.

A few weeks later, I flew to Cleveland, and made it just in time to see the last of about 200 protesters storm into Cleveland city hall, their signs and T-shirts declaring JUSTICE FOR TAMIR as they marched up to the council chambers for the body’s final meeting of the year.

That night there was a stinging winter breeze blowing off Lake Erie and drifting through a largely empty downtown Cleveland. Typically, this section of the city would be quiet at this time of night, just after dinner on a weekday, with city employees gone from the public buildings – courthouse, administrative offices, city hall – that line these blocks. But on this night, there was a strong, steady sound of dissent.

“This is a movement, not a moment,” declared Lorenzo Norris, a local pastor, as he led the racially diverse if largely young group of protesters into the council chambers. The Cleveland protesters were incensed by a recent federal review that had concluded that their police officers regularly exerted excessive force during routine interactions and pulled their guns (and their triggers) inappropriately.

That investigation had been sparked by another shooting in November 2012, during which Cleveland police officers opened fire on a car that had led them on a chase, discharging 137 bullets into the vehicle, only to later discover that both of those killed had been unarmed. Like their protest brethren in Ferguson, the Clevelanders contended that local elected officials hadn’t done enough. “We want change,” Norris told me as I caught up with the group. “We must have change.”

After the protest, I drove over to see my old friend Colin. We weren’t exactly surprised by Tamir Rice’s death. We knew the Cleveland police weren’t known for their rigour or calculated decision-making – in fact, in the last decade, the Department of Justice had issued not just one but two sets of findings that concluded the department routinely violated the civil rights of the city’s residents. As young black men from the suburbs riding through the city in cars a little too nice to have either of us behind the wheel, we’d had our fair share of colourful interactions with Cleveland’s finest.

At some point in high school, my best friends and I all had a running joke about “the talk”, which most of them had been given by a father or mother or some other relative. The underlying theme of this set of warnings passed down from black parents to their children is one of self-awareness: the people you encounter, especially the police, are probably willing to break your body, if only because they subconsciously view you not only as less than, but also as a threat.

Find almost any high school-age black male and ask him about “the talk”. Neither of my parents ever really gave it to me, but I heard “the talk” secondhand from the mothers of a few friends. Besides, when you grow up in a mixed-race home – my mother is white, my father black – no one has to tell you that one half of your family looks different than the other and that you need to pay attention. Close attention.

Say “yes sir” or “yes ma’am” to any officer you encounter. If you get pulled over, keep your hands on the wheel. As we drove around in Colin’s car listening to Cleveland rap, we’d keep our wallets in the centre console. That way, we wouldn’t have to reach into our pockets. Above all, we knew to never, ever run in the presence of a police officer. That’s just asking for trouble.

While “the movement” was born in Ferguson in the summer of 2014, it had been conceived in the hearts and minds of young black Americans at different points in the preceding years. One of these moments came in July 2013 with the Florida jury’s decision to find George Zimmerman, the neighbourhood watchman who shot and killed Trayvon Martin, not guilty.

That year was a major awakening point not just for me but also for other young black men and women across the country. Each story of a police shooting solidified the undeniable feeling in our hearts that their deaths and those of other young black men were not isolated. Peaceful black America was awakened by the Zimmerman verdict, which reminded them anew that their lives and their bodies could be abused and destroyed without consequence. Trayvon’s death epitomised the truth that the system black Americans had been told to trust was never structured to deliver justice to them. The “not guilty” verdict prompted the creation of a round of boisterous and determined protest groups, initially Florida-based, although they would eventually expand nationally.

Across the country, at a time when Twitter had yet to become the primary platform for news consumption, a 31-year-old activist in Oakland named Alicia Garza penned a Facebook status that soon went viral. She called the status “a love letter to black people”.

“The sad part is, there’s a section of America who is cheering and celebrating right now. and that makes me sick to my stomach. We GOTTA get it together y’all,” she wrote, “stop saying we are not surprised. that’s a damn shame in itself. I continue to be surprised at how little Black lives matter. And I will continue that. stop giving up on black life.

“Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter,” she concluded.

Her friend and fellow activist Patrisse Cullors found poetry in the post, extracting the phrase “black lives matter” and reposting the status. Soon the two women reached out to a third activist, Opal Tometi, who set up Tumblr and Twitter accounts under the slogan.

“Black Lives Matter is an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise,” Garza wrote in the group’s official history of its founding. “It is an affirmation of Black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression.”

While the phrase is now the name of an organisation and is often used to describe the broader protest and social justice movement, Black Lives Matter is best thought of as an ideology. Its tenets have matured and expanded over time, and not all of its adherents subscribe to them in exactly the same manner – much the way an Episcopalian and a Baptist, or a religious conservative and a deficit hawk, could both be described as a Christian or a conservative, yet still hold disagreements over policy, tactics and lifestyle. For the young black men and women entering the adult world during the Obama presidency, the ideology of Black Lives Matter, not yet an organisation nor a movement, carried substance, even heft. It was a message that resonated with the young black men and women who had been so outraged and pained by the Zimmerman verdict. And the decision by Tometi to focus on Twitter and Tumblr, then second-tier social media outlets, instead of Facebook, proved a stroke of strategic genius.

Both networks allow for more organic, democratic growth. Unlike Facebook, in which virality is determined by algorithms, visibility on Twitter and Tumblr is determined directly by how compelling a given message, post, or dispatch is. A phrase like #blacklivesmatter, or #ferguson, or, later on, #BaltimoreUprising, can in a matter of moments transform from a singular sentence typed on an individual user’s iPhone into an internationally trending topic. #blacklivesmatter didn’t catch on immediately, but its time would soon come.

As writer and historian Jelani Cobb wrote in the New Yorker, in what remains one of the definitive profiles of the creation of the organisation: “Black Lives Matter didn’t reach a wider public until the following summer, when a police officer named Darren Wilson shot and killed 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson. Darnell Moore, a writer and an activist based in Brooklyn, who knew Patrice Cullors, coordinated ‘freedom rides’ to Missouri from New York, Chicago, Portland, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Boston. Within a few weeks of Brown’s death, hundreds of people who had never participated in organised protests took to the streets, and that campaign eventually exposed Ferguson as a case study of structural racism in America and a metaphor for all that had gone wrong since the end of the civil-rights movement.”

As of March 2016, the 10th anniversary of Twitter, the hashtag #blacklivesmatter had been used more than 12m times – the third most of any hashtag related to a social cause. At the top of the list, however, sits #ferguson, the most-used hashtag promoting a social cause in the history of Twitter, tweeted more than 27m times.

The Movement for Black Lives – as activists had begun calling the protest movement – and the national push for police reform, had faded from the national consciousness during the first months of 2016. There were bursts of attention, but in each instance Americans’ focus on race and justice landed like another strong wave, only to recede right back into the ocean. Six months into 2016, my colleagues and I were working on an analysis of the number of Americans killed to date, and had discovered that even after more than a year of protests and outrage, police nationwide were on track to take more lives in 2016 than they had in 2015. Yet none of the men and women killed by police in 2016 had received the same level of attention from the media or had galvanised activists as much as those killed just months earlier.

For racial justice activists, the presidential election was an opportunity to pressure candidates to adopt positions on policing and criminal justice reform, as well as to speak out on other issues of racial disparity.

“People know that the police are still killing people. What we’ve got to figure out now is what a victory looks like,” Kayla Reed, the Ferguson protester still working for the Organization for Black Struggle in St Louis, told me in early 2016. “There isn’t going to be a single bill passed that will suddenly encompass all of the ways the system marginalises black and brown people. We have to redo the whole damn thing.”

Many of the young activists who had been driven into the street by the police killings of 2014 and 2015 had begun to move away from daily protesting and organising work. Robust conversations circulated about viral videos of the deaths of individuals and the fetishising of black death. Perhaps, some argued, not every video needed to be shared and played on a constant loop.

In early July 2016, two killings reawakened the movement. Videos circulated on social media of the police shootings of two young men, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. Among the cities that hosted major protests was Dallas, where the police had gone to great pains to support the protesters, cordoning off areas for demonstrators and posing for photos next to signs calling for reforms and justice. It was here that a single gunman attacked white officers in what he later told police negotiators was a targeted retribution for the police killings of black men.

A week later, another lone wolf attacked officers in Baton Rouge, killing three. The deaths and injury of the officers in these two cities again shook the nation, underscoring with renewed urgency the depth of the anger and distrust towards police still coursing through America.

The attacks on police officers enraged the law enforcement community. In a country with millions of easily accessible guns and an increasing national distrust of institutions – specifically the police – it wasn’t hard to imagine the ease with which someone determined to harm officers could carry out such an attack. “With the number of police shootings that have occurred that seem to be totally unjustified, somewhere in this country, someone was going to do such a thing,” John Creuzot, a former prosecutor and judge in Dallas, told me after the shooting.

After the Dallas attack, Barack Obama convened a 33-person conference at the White House, a conversation that ran for four-and-a-half hours – among the longest single-subject conferences of his presidency. The attendees were a mix – young activists such as DeRay Mckesson, civil rights stalwarts such as Al Sharpton, police chiefs and heads of several major police unions, and government officials including the attorney general, Loretta Lynch.

As he facilitated the conversation, Obama often glanced to his left, at Brittany Packnett, a 31-year-old Ferguson protester and co-founder of Campaign Zero – a policy-oriented activist arm that pledged to put forth recommendations for how “we can live in a world where the police don’t kill people”. This was at least the third time Packnett had met Obama, who after one meeting had been so struck by her command of the room that he pulled her aside to encourage her to one day run for office. She had applied for and was accepted to a spot on the Ferguson Commission, the taskforce convened by Missouri governor Jay Nixon after the unrest in 2014. Next, Obama invited Packnett to join his president’s taskforce on 21st-century policing.

I asked what had brought her from the barricades into the policy making rooms – by now, Packnett had joined street protests in more than half a dozen cities.

“Everyone has a role,” Packnett said. “There are some people who need to be the revolutionary, and there are some people who need to be at the table in the White House. And I knew it was my job to translate the pain I had seen and experienced in the streets and bring it into these halls of power.”

Packnett explains the protest movement as a series of escalating waves. Its conception came from the deaths of Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis, which mobilised black Americans in a demand for justice. Its grand birth, first in Ferguson and then throughout the nation in the autumn of 2014, was prompted by the deaths of Eric Garner, John Crawford and Michael Brown, the cases that showed justice for those killed by the police was not forthcoming. As the list of names grew, so did the urgency of the uprising that would become a movement. 2015 brought a third wave of anger and pain: Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, Samuel DuBose – another round of death in which the pleas for police accountability became demands. As Obama prepares to leave the White House, it remains to be seen whether the movement birthed by the broken promise of his presidency will live on through the season of his successor.

“The protests will continue,” Packnett said confidently when I called her from Cleveland on the first night of the Republican national convention in July. “We’re going to work to continue this level of engagement with the next administration; there’s just too much at stake.” While the targeted killings of the officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge prompted some commentators to declare the movement dead, the activists have not gone quietly.

A few days later came the non-fatal shooting in North Miami of behavioural therapist Charles Kinsey. Kinsey was lying on the ground with his hands in the air, begging not to be shot as he tried to soothe his autistic patient, when an officer fired his gun three times. “I was thinking as long as I have my hands up ... they’re not going to shoot me,” Kinsey told a local television station from his hospital bed. “Wow, was I wrong.”

In the days after the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, thousands of people used an online tool provided by Campaign Zero to petition their local elected officials to demand police reform. In mid-July, as the political media gathered in Cleveland for the GOP convention, thousands of demonstrators took to the streets in more than 30 cities.

“We have no choice but to keep going,” Packnett told me. “If one of the central demands of the movement is to stop killing us, and they’re still killing us, then we don’t get to stop, either.”

They Can’t Kill Us All by Wesley Lowery (Penguin, £9.99). To order a copy for £8.49, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.