On the Sunday after Thanksgiving, I rushed my wife Paula to the emergency room at Baltimore's Sinai Hospital. What she thought was just the stomach bug du jour turned out to be a life-threatening condition that would take her to nearly every corner of Sinai. Three weeks later, I would find myself sitting in the surgical waiting room at Sinai as a rock-star surgeon operated on her robotically in front of a crowd of other doctors.

It wasn't my first time wandering the halls of the hospital; 12 years ago, my son was hospitalized at Sinai when he had appendicitis. Much has changed in those 12 years, but what surprised me more is what hasn't.

I've spent a lot of time in the hospital over the past few weeks and have become all too well acquainted with the technology there. I've covered health IT in the past, but there's a big difference between talking with people about what's happening in the health industry with technology as a whole and experiencing it from the chair next to a hospital bed.

Don't get me wrong—I have nothing but praise for the people who treated Paula during her stay. Sinai is not just another hospital, it's the flagship of one of Baltimore's biggest healthcare systems and, while it doesn't have the sheer industrial size of Johns Hopkins, it's a major teaching hospital in its own right. And Sinai's emergency room is one of the best in the city, handling a huge volume of walk-ins and ambulance-delivered patients. But what I found is that medical IT remains a patchwork quilt of Star Trek and steampunk—one that seems to work almost despite itself.

Day 1: Back to the future

When we arrive just after noon, we fly through the ER's triage—apparently so fast that the receptionist checks off a box in my wife's electronic registration indicating she is uninsured. Despite other people taking the information four more times, the insurance information doesn't take until I talk to accounting later.

That is a minor annoyance; a larger one is not knowing what is going on. It's a busy Sunday, and once they give Paula a painkiller and sedative, we see the ER doctor a few times in passing. Having been in an emergency room frequently over the past decade thanks to kids' extracurricular mishaps, I know the drill. But in this case, the only hint at where the diagnosis is going is which test Paula is getting rolled off for next: ultrasound, CT scan, and multiple blood draws.

So I start to poke around, trying to decipher what I can from the tech around me—mostly to keep myself occupied as Paula's sedation and painkillers lull her to sleep. The first thing I notice is that everything but the bed and chairs in the room is wirelessly networked—the Computer On Wheels (COW) workstation, the IV infusion pumps, the machine taking Paula's vitals. And there's a full Wi-Fi signal on my iPhone—the network is accessible with a guest login.

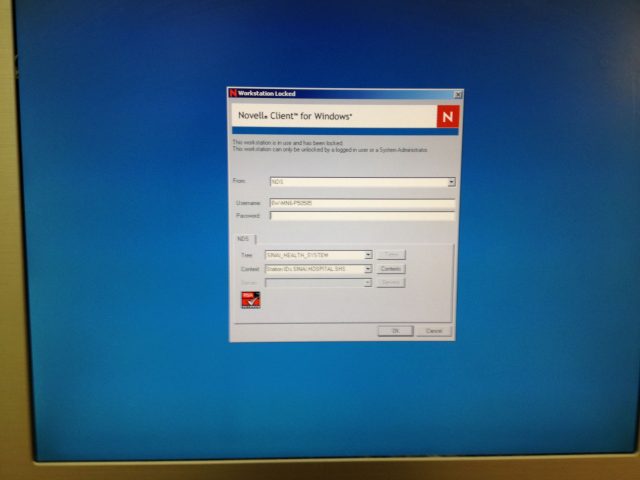

While the wireless network is modern, the computing infrastructure is less so. The roll-around COW workstation the nurses use to enter data—like every other computer I will encounter during the next three weeks—is running Windows XP and a NetWare for Windows network client.

Hospitals are notoriously conservative about operating system upgrades, both for financial reasons and because the medical software industry has been slow to certify their applications for newer versions of the Windows OS; the infusion pump management software for the IVs in my wife's room is still available only for Windows 2000 and XP, for example, and the data connector to manage the system's software requires a nine-pin serial port.

The throwback nature of the computing infrastructure applies to the COW PCs and all the other workstations in the hospital as well—nearly every one I look at is a vintage 2006 HP/Compaq small form factor system, and some still have the Compaq OEM Windows XP wallpaper.

Three hours pass. Paula wakes up and asks me what's taking so long, so I go out to try to find an answer. Out in the bullpen of desks at the center of the cluster of ER beds we're in, there's a flat-screen display with a spreadsheet-like status chart for each patient. I deduce from the data on it that Paula is being admitted—a room number pops up next to her name.

But it seems like more hours passed before we see the ER doctor and get the diagnosis: the phrases "big-time pancreatitis" and "worst I've ever seen" are dropped casually.

I pull out my phone to Google "acute pancreatitis." It's not pleasant reading. I call home and tell our kids what's going on as a transport technician arrives to roll Paula off to the elevator.

Bring your own, or wheel it in

Twelve years ago, the general ward of the hospital enforced a cell phone ban. But now, it seems like everyone is carrying one—even the patients. I bring Paula her iPad and set up Netflix so she has some other entertainment beside the basic TV service in her room. (Unfortunately, Netflix was blocked by the hospital's network).

While the hospital staff isn't bringing their own devices to work, the physicians from Paula's primary care provider's practice are. The gastroenterologist, surgeon, and "patient care coordinator" are constantly texting each other with the latest information on the case; the iPhone seems to be their tool of choice.

As of Monday morning, it's looking fairly routine, though the surgeon says Paula's pancreas looks "scary." For now, though, Paula is just under observation, and everything we hear indicates she'll be better soon, aside from needing her gallbladder removed. I begin to dig in for the wait, bringing my laptop to the hospital to try to work while I keep her company.

The Wi-Fi network for guests is isolated from the hospital's general network at the access points—at least the hospital has done a good job of hiding the SSIDs for its internal network. It also has content filtering in place, as I find out when searching for an image for a story I'm writing, and it blocks Flickr as "pornography." I quickly defeat the filter by switching on a VPN connection.

I try again the next day and find that using a VPN connection going to an IP address in Sweden has apparently caused some security concerns, and I'm blocked. (My apologies to any network administrators at Sinai who may have thought Anonymous had infiltrated their network.)

The nurses push COWs into the room to record each round of medication and vital signs measurement, scanning Paula's wristband each time; there's a consistent problem with the barcode reader, and the technicians doing blood pressure and temperature roll their eyes as if this is a common problem.

For all this electronic medical record technology, a surprising amount of paper still gets handled. Every time I see one of Paula's doctors on the case, they're working with a paper chart in a binder, hand-noting instructions—since they're not hospital staff, they likely don't get access to the hospital's EMR system.

There's also some confusion about what exactly the instructions are. On November 30, Paula is told she can start to get clear liquids. But her surgeon quickly reverses that—just after Paula orders up some jello.

Throughout all this, there's not a whole lot of information to work with on our end. Paula is starting to get stir-crazy. The night of December 2, she goes for a CAT scan, posting to Facebook from her phone afterward, "No actual cats are involved in a cat scan. :(" She jokes that Guy Fiere could redeem himself if he came up with a better execution of the barium contrast drink.

The next morning, I am driving my son and daughter to school when my phone plays my wife's designated ringtone. My son picks it up for me: "Hi…he's driving. Oh? OK, I'll tell him. Bye." He hangs up, and puts the phone down casually. "They're moving her to the ICU, she said."

It turns out that there's been much more damage to the pancreas, and some of it has necrotized. Paula's surgeon transfers her case to another doctor who can write orders at the hospital—a young Lebanese surgeon who is an expert in robotic surgery and who has experience in pancreatic surgery. He is also Sinai's "intensiveist" for the week. The move to the ICU is to monitor Paula's condition more closely and bring as much attention and technology to bear on the issue as possible.

reader comments

92