Honest Writing Is Funny Writing

Memoirist Sean Wilsey says he knows he's finished with a story when it makes him laugh.

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Claire Messud, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Literature at its most serious is almost always funny. It’s hard to name an authentic great—Dickens, Faulkner, Zadie Smith—who’s not a gifted comic, too. In our conversation for this series, Sean Wilsey, author of the essay collection More Curious, made his case for why literature needs laughter—though he suggested that successful humor requires way more than punchlines and good timing. With help from a line by the classic Italian memoirist Casanova, Wilsey explained why good writing asks us to do a tricky thing: Let go of what we hold most sacred, and poke fun at ourselves.

More Curious expands 12 essays originally published in venues like The New York Times Magazine, GQ, and Vanity Fair. In the introduction, Wilsey cites as his heroes the novelist Thomas Pynchon and the great New Yorker profile writer Joseph Mitchell—here, the madcap, meta-textual antics of the former blend with the latter’s brand of photographic portraiture. In an array of playful essays with serious hearts—there are pieces on NASA and skateboarding, New York City’s rats and Shake Shacks, the World Cup and U.S. road trips—Wilsey explores the tension between staying home and finding an escape.

Formerly an editor-at-large for McSweeney’s and New Yorker staff writer, Sean Wilsey lives in Marfa, Texas—the remote town and artist’s enclave that he chronicles at length in the book. (The essay describes one of the odd souls who was his neighbor for a spell—a novelist named David Foster Wallace.) Wilsey’s memoir, The Glory of It All, was a New York Times bestseller. He spoke to me by phone.

Sean Wilsey: Years ago, I came across a book called Casanova’s Women, a feminist reinvestigation of Casanova and his work. The writer, Judith Summers, went back to study the women Casanova seduced and wrote about. What were their lives like, and how did these seductions affect them? In his writings, at least, Casanova made a huge point of humanizing the people he got involved with sexually. He claims he treated them—certainly by the standards of his day—with tenderness and respect. But Summers’s book, which is very good, is skeptical of his account, and shows how often women’s lives were ruined by sleeping with men before they were successfully married.

I found myself intrigued. I’d never read Casanova before, which suddenly seemed like an oversight. I’m working on a memoir largely set in Italy, part of which concerns my experience as an apprentice gondolier in Venice. Casanova was a Venetian, and one of the greats of Italian literature. I realized I had to know him.

The memoir itself is enormous, written in 12 volumes that average maybe 350 pages each. It can be an imposing work: Though the books are written in clear prose, many passages bog down into period mores. There are lengthy explanations and rationalizations of what he was doing within the context of values of his time—values that no longer exist, and aren’t especially interesting when discussed ad nauseum. In spite of this, Casanova’s History of My Life is one of the most amazing things I’ve ever read.

The seductions are fascinating, even if they have a repetitive quality. All his affairs seem to progress according to a fixed pattern. First, he falls in love—or claims to fall in love. He never has any assignation that isn’t full of every feeling that you could possibly have for someone; they’re rarely just animalistic couplings. (Though there is one scene I can think of where he literally manages to screw somebody through the bars of a prison.) Eventually, though, there comes a point where “every favor has been granted,” to put it in the language of Casanova. At that point, he gets bored and moves on. After a while, you want to scream—you idiot! He misses out on so much of life by never allowing these relationships to go beyond the initial attraction. But the pattern continues.

By the end of his life, Casanova found himself in greatly reduced circumstances. He worked as a librarian for a nobleman in Bohemia, and was considered a ridiculous, comical figure. And you have to admit: He blew it! There were moments when Casanova was on top of the world. He invented the French lottery—and as one of the guys who ran it, made buckets of money. He was very happy after he escaped Italian prison for Paris, and had plenty of opportunities to settle down. But he never did. And so he came to the end of his life—isolated, aging, and alone.

You know how Rebecca West says that half of us wants to be in the house, surrounded by our contented offspring and grandchildren—but the other half wants to burn that house to the ground? Well, Casanova just fully burned the house to the ground.

Still, as an old man, he cranked out these memoirs. In one of his letters, he wrote a line explaining the experience and what it meant to him:

"I am writing my life to laugh at myself, and I am succeeding."

I like the word “succeeding,” here, because it suggests a new maturity in Casanova. You might think he’d have a worldly definition of success—he was obsessed with status in a status-obsessed time. He was from a humble background, an actor’s child, and for most of his life he badly wanted to be viewed on equal footing with the nobility and the ruling class. To me, this line shows he actually grew as person—in a way that the memoirs don’t, quite. It shows that, by the end, he could finally laugh at his gambling and his social striving and his endless affairs. Something about this line deepens the whole project for me.

I also think this line contains crucial insight about the process of writing one’s own life. Writing memoir, after all, is usually a decision to engage with the most painful, fraught, or embarrassing portions of your experience. Memoirs, like most narratives, are about conflict and drama and pain. When life is good—or even more than good, when life makes sense—I really don’t feel any desire to write about it. Only when life becomes painful, when I’m suffering, do I feel like I’ve got the material to work on the page.

But just writing down one’s troubles isn’t enough. You have to bring new perspective and insight to your suffering. For me, there’s a sure sign I’ll be able to muster the maturity to it takes to make art out of my life: When I’m finally able to laugh at a younger version of myself.

The things we can’t laugh about are the things we haven’t grown out of yet. Not laughing is, in some ways, a failure to grow beyond things that are still too close, too present, too hurtful. Laughter is a release from all that. It shows we’ve moved on. I don’t think I’m ever ready to write about an experience or period of my life until I have distance from it—the kind of distance laughter signifies.

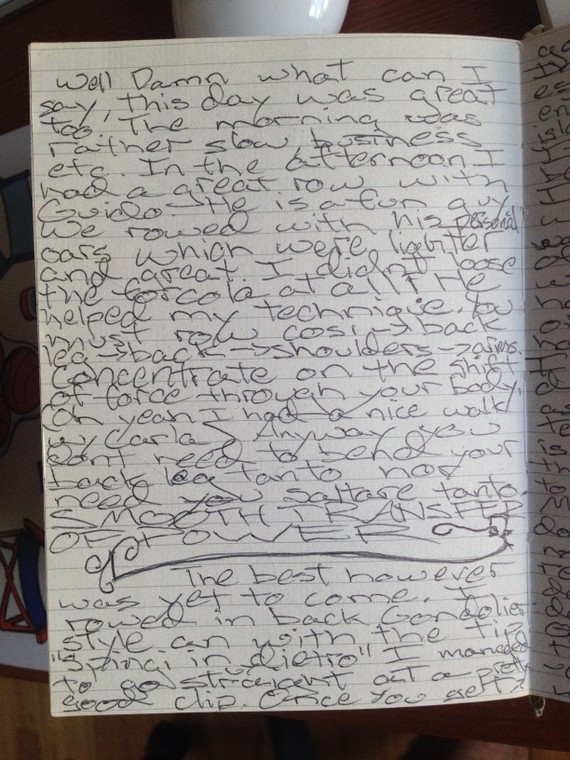

I’ve kept a journal on and off for the last 25 years—since my early 20s—and when I look at that stuff, it’s agonizing. I have this churlish, aggrieved tone that would be totally unsuited to any piece of published writing. This writing is useful for remembering what happened when, and in what order, but I can’t use any of the writing itself. I hadn’t digested those experiences yet, or they mattered too much to me then.

An excerpt from my journal, written when I was 18:

I will never be quite the same after Venice because it has shown me that man can create true beauty and that I believe is Man’s purpose.

On its own, this is so pretentious and self-important. Horrible! I cringe to think of writing these words—a sign that my perceptions, thank god, have deepened since then. Had I written these words just last year, I might want to burn them or hide them in a drawer. But because I have enough distance from who I was when I was 18, I don’t have to feel ashamed of what I did or said or wrote. I can laugh.

That’s beautiful thing: As life goes on, everything that once seemed important eventually doesn’t seem that way anymore. The things that felt so serious, so crucial and agonizing, lose urgency with time; what’s left is the comedy of it. Not that laughter takes away the seriousness of one’s original experiences, of course. Important or troubling experiences stay with us—but, with time, they begin to contain humor within them, too. I think there’s something dishonest about writing that isn’t funny. I can’t engage with a piece of work without an element of humor to it. Laughter and levity are important aspects of human life, even at its darkest, and writing that lacks those qualities denies the full richness of experience.

Besides, there’s nothing funnier than looking back on a poor, pitiful version of yourself. There’s a section in the book—a little bit of it was in the New Yorker last year—about being an apprentice gondolier. As part of this section, I had an extended episode where I stowed away on the Mayor of Venice’s private boat. I interviewed him, and had a crazy conversation that I recorded the whole thing. This mayor was a slippery individual. He’s currently under house arrest for embezzlement. It was clear how crooked he was when I interviewed him, and it was a tense and strange conversation. And I could not listen to the tape. I just couldn’t listen to it for a long time, when I did it was just pure agony. But, ultimately, I realized that the whole exchange was hilarious.

As a memoirist, you have to be willing to see yourself as a little bit absurd. And it’s much easier to see yourself 20 years ago as absurd. With stuff that’s well in the past, it’s as though you become one of your characters. I’m far enough away from “Sean Wilsey” in the memoirs that I see him sort of as a journalistic subject—yet one I have deep, insider knowledge of, because I used to be him. Still, I feel very little as though he’s still me. (And that’s a relief.)

I think there would be something really sad if you continued to take yourself seriously throughout your life. It would mean you hadn’t changed at all, and the idea that you haven’t changed is a deeply tragic one. That kind of stasis is certainly a dangerous quality in an artist. If you’re just going to keep doing the same thing over and over again, how interesting is that?

Being able to grow in this way—to sustain the kind of growth that ultimately allows laughter—is a crucial skill for writers, because it allows you to move past your initial, limited conception of a project. When creative projects refuse to follow our plans for them, that’s a good thing. In my journalism, I’m surprised by how often I end up saying the very opposite of what I thought or hoped to say when I began a piece. If I think I’m going to attack on an idea or person, say, I’ll end up having a more nuanced view, perhaps even a kind of respect for what I once had hoped to skewer. That’s the definition of growth.

(This isn’t true for all subjects, of course. You know that Donald Trump is just an execrable human being, and no amount of time spent with him is going to change that.)

It happens, too, when you write about the people in your life. There are people whom I’ve known for decades now, and I’m constantly understanding new things about them as I work with them on the page. I come to new conclusions about who they are, and why they did the things that they did—especially with people who were adults when I was a child. Now that I’m raising kids of my own, I end up having totally different insight into how certain decisions end up getting made.

So, you have to be able to laugh at the scope of your ideas when you began, and let go of the ideas you thought you had before you began the work. The essay in the collection that was the was the hardest and most agonizing for me is a piece about driving across the country called “Travels with Death.” It’s an embarrassing thing to admit, but I really felt like: “I’m writing this piece because I’m going to explain America.” Of course, that wasn’t possible—I had to learn to let it go.

I love the way Casanova locates his idea of “succeeding” not in amount of acclaim or size of readership—but in how well he can laugh. Well, I feel good about something when I’m at peace with it. For me, the one-word definition of success is peace. And I only feel at peace with something—like I can put it away, that I’ve understood it and am done with it—when I get to the point where I feel like I can laugh about it. There’s a funny thing that happens as I work. When I start revising, I just spend draft after draft thinking how much it sucks. Maybe there are bright spots here and there, but most of the time it’s big slash marks through every page. But, then, an amazing thing happens—as I get closer to the final copy, the prose starts to be funny. It gets to the point where it’s finally clipping along, and it becomes fun—the humor only really comes through at that moment. Suddenly, there’s this built-in amnesia where you forget how hard it was until that point—and it all becomes a pleasure. Laughter is the sign that I’m done.

I think comedy is the deepest form of release. We’re prisoners of the things that we’ve done and the circumstances we’ve lived through, and we can never change our pasts. But there’s a key that can let you out of all that, that tells you you’ve come to understand something and are at peace with it. You know when you’re holding the key—because you can laugh.