In the old days, the Internet was famous for being able to survive an outage—a downed data center here, a severed undersea fiber optic cable there—without people losing access to most of the network. But a series of questionable decisions by some of the world’s most important internet companies has changed that equation. Now, the web is rife with a growing number of single points of failure—glitches that can affect a significant portion of the web all at once.

Last night’s “Facebook outage” typifies the new, more vulnerable web. For up to an hour, visitors to some of the web’s most popular sites were re-directed to Facebook.com and confronted with an error message like this.

Almost all of the sites affected were media outlets, including CNN, NBC News, the Washington Post and the Gawker network, but the outage also affected sites like Yelp. Ominously, New Yorkers trying to prepare themselves for a “historic” blizzard couldn’t access Weather.com.

How could a single bug at Facebook affect so many sites? Facebook has yet to comment beyond saying the issue “was quickly resolved, and Login with Facebook is now working as usual.” (We’ve reached out to Facebook for more.) It seems that the problem was with the Facebook Login feature, which, as you can probably guess, is the Facebook-based login system that other sites use to register users. (If you’ve ever been offered the opportunity to log in to a site using your Facebook identity, you’ve seen it.)

Because of the ubiquity of Facebook Login—and, hence, the user-tracking system that powers it—a single problem with Facebook Login was able to affect every site that used it. Thus, what was likely the error of a single programmer blocked access for tens of millions of people.

Parallel issues at Amazon

Amazon Web Services hosts data and websites for a substantial portion of Silicon Valley startups. Normally a back-end affair that no one but developers would know of, it’s become famous because whenever AWS loses a data center, millions of people can’t stream movies from Netflix. (The most recent Netflix outage was Christmas Eve of 2012.) Amazon itself is affected by these outages, and the company lost an estimated $4 million in sales during a single 49-minute outage in January 2013.

Amazon’s hosting service is cheap, which is one reason that so many companies use it. By doing so, however, they accept that outages are inevitable. Unlike the old web, when outages generally only affected a handful of sites, AWS has become so popular that when it goes down, half the web can go with it.

Expediency and profit over robustness

Why are some of the world’s most popular web sites and services tolerating this new, less robust internet? The simple answer is that it’s integral to how they control costs or (if they’re mature) turn a profit. Facebook Login, for example, has exploded in popularity with publishers because, like the related Facebook Connect service—that’s what powers all those “Like” buttons—it drives traffic to their sites.

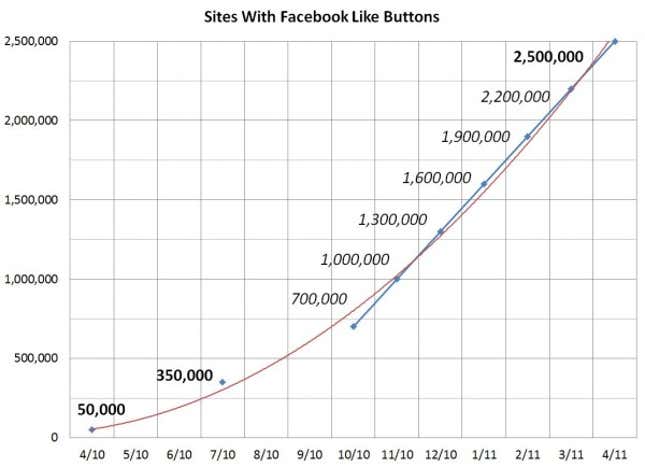

Here’s a graph from Danny Sullivan at Search Engine Land showing the explosive growth in the number of sites with Facebook Connect since its launch:

Integrating Facebook’s services can triple social referral traffic to their sites. So what if it means that Facebook now has the power to take them down entirely?

Amazon has led to similarly short-sighted thinking among customers. While the company strives to make AWS as robust as possible, it’s mostly up to their customers—i.e., CTOs and developers at sites like Netflix—to create backup and contingency plans should AWS lose a data center or have other issues. In order to keep costs low, these backup plans might not be as bulletproof as they would be for, say, a large bank.

Is a shakier Internet the price of convenience?

Both Facebook and Amazon have been unique enablers of young startups. Without the boost from Facebook’s app ecosystem and new ad placements—as well as the cheap hosting and other services offered by Amazon—many would have had much more trouble getting off the ground. The problem is that even as startups mature, they continue to rely on these services. As Amazon becomes more dominant as a services provider, and Facebook’s Login feature becomes the default standard for identity on the web, these problems will only worsen. There are two solutions: Facebook and Amazon could own up to their centrality in the new web, or startups and mature online businesses could deliberately make themselves less dependent on them.

The big unknown, however, is what other web-wide vulnerabilities are out there. No one anticipated the Facebook Outage of 2013 until it happened, and it seems likely that other black swans lurk in the web’s future.