Nairobi, Kenya

Most of what Luo Songxu knew of Africa when he moved there last year came from a 1991 rock ballad by a Hong Kong pop star, Wong Ka Kui. It was called “Amani,” or “peace” in Kiswahili.

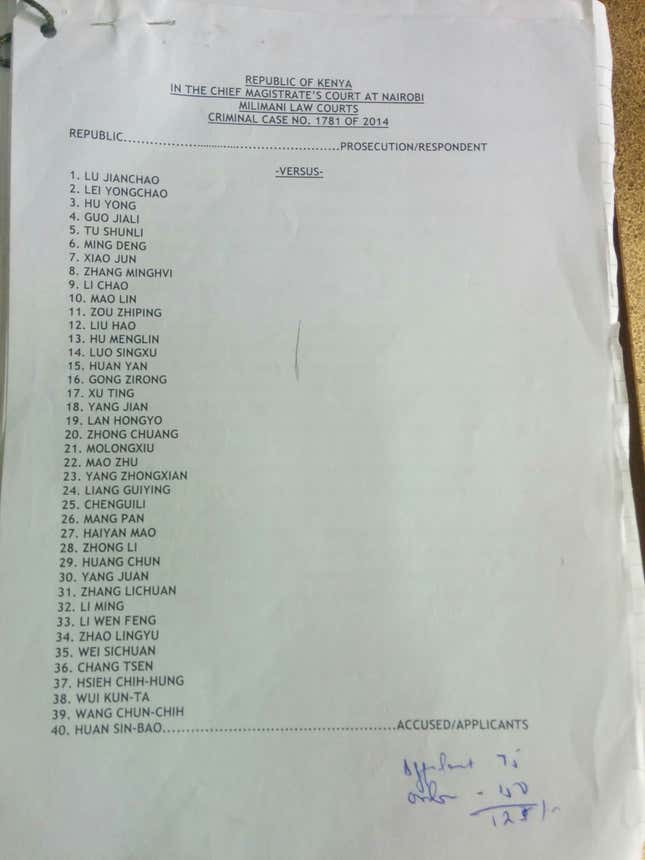

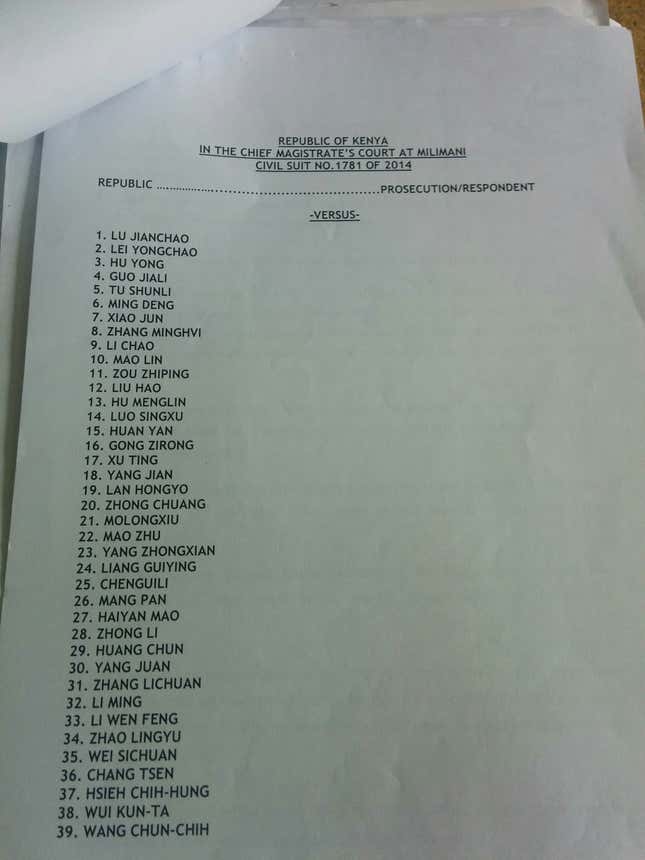

But peace is the last thing the 28-year-old has experienced since he came to Nairobi from his hometown in China’s western Sichuan province. Less than three months after his arrival, Luo and 76 other Chinese were arrested. They have been in jail for nearly a year, accused of running an illegal call center and engaging in or intending to commit cybercrime—charges of which they say they are innocent. If convicted, they face up to 15 years in prison. (Their next hearing is on Nov. 23.)

Luo and his compatriots are the largest group so far of Chinese nationals to be charged in Kenya. They are the other face of China’s economic expansion in Africa—not the well-paid envoys of a colonial power, but migrant workers, people who have more in common with their African counterparts seeking a better life in Europe. Many of them come with almost no knowledge of the region, no contacts, and little support from their own government when things go wrong.

And their arrests are emblematic of a slowly brewing backlash against Chinese immigration to the continent.

“To be honest, I was really naive. I thought going abroad would be fun and that I could also work. I knew Wong’s song and thought there would be more human rights [in Kenya],” Luo tells Quartz, seated on a wooden bench in the basement of the Milimani Court House in Nairobi that says “Advocates only.”

Luo wears a black puffer coat that matches his short black hair. He is slim with an impassive face. The only sign of emotion is a clenched jaw after his lawyer tells him that today’s hearing, when testimony from the last witness for the prosecution was to be heard, has been delayed for the second time in two months. That means more time waiting in prison. “Here, I think we have no rights,” Luo says.

Not your typical colonialists

As Chinese investment in sub-Saharan Africa has increased 40-fold since 2003, the number of immigrants has grown too. Estimates of their numbers are vague, but range from a few hundred thousand to over 1 million.

It’s not many compared to the Chinese populations in Southeast Asia, the US, or Europe, let alone the giant internal migrations within China—expected to reach 290 million (link in Chinese) by 2020. But unlike previous waves of Chinese emigration abroad, which came from three main coastal provinces, the immigrants to Africa come from all across China, from different social classes and professions. There are more women and more people of all ages.

The most visible are often the wealthy Chinese businessmen, or the managers and staff of large state-owned Chinese companies. Less noticed are people like Luo—the traders, cooks, hairdressers, and other holders of odd jobs. Less educated and poorer, they often come from Chinese regions that the country’s economic boom of the 1990s and 2000s never quite reached, or where jobs have become scarcer as the economy has since slowed. They might stay forever or just a few years, working in shops and small-scale import export businesses, living in the same neighborhoods as their hosts.

These people interact with African society differently from other foreigners. “They engage at a more grassroots level, in small retail businesses, in small towns and rural outposts. It really is a sort of globalization from below,” says Yoon Jung Park, a senior research associate at Rhodes University in South Africa as well as an adjunct professor at Georgetown University.

Economic opportunities aren’t the only thing drawing them to Africa. It can be a welcome break from China’s polluted, overcrowded cities. It may be an escape from the censure and lack of political freedoms at home. A more often cited reason is that places like Kenya offer a break from China’s rat race—the competition to get into a good school or job, the search for a husband or wife, or the difficulty of earning enough to buy a home or car.

Luo fits this mold. He studied machine automation after graduating high school, but had spent most of his adult life working as a cook, driver, and general handyman to support his family. The economy wasn’t bad in his hometown of Zigong, a city of two million people, small by Chinese standards, but the idea of adventure appealed to him. When he saw a flier advertising a job in Kenya that included airfare, room and board, and a salary, he thought about China’s flourishing relationship with the African continent and the song by Wong Ka Kui, extolling peace and love inspired by the Kenyan people.

“They stay not just because they want to make money but because they love Kenya,” says Wayne Wong, a Malaysian-Chinese pastor who works on promoting cultural ties between the Chinese community and locals in Nairobi and has been translating for the group during court hearings. “There’s less competition, more space, better quality of life.” He quotes a friend of his, a Chinese hotelier that has just settled down in Nairobi, “Once you get the Chinese to Africa, they never leave.”

“In the wrong place at the wrong time”

Luo arrived in September, expecting to be assigned work as a driver. His group—many from the same town, Zigong, in Sichuan province—were mostly in their 20s, with only a middle-school education. They were put in a house in Runda Estate, a spacious suburb protected by guards and security fences in northeast Nairobi. Twenty-seven are from Taiwan, and one is from Thailand. According to Luo, once they arrived they were told to stay inside the house. “We weren’t doing anything. After we got here, all we did was sleep and eat. We never saw the boss,” he says.

On Dec. 2, Luo and a few others were playing poker at the house when plainclothes policemen stormed it. The police ordered them outside, and rifled through their things, seizing cellphones and laptops. Bewildered, someone in the group managed just one word in English—”Why?”—before they were pushed into a van and taken to a nearby police station.

Local media have reported that the group was running a “command center” for hacking, money laundering, and eventually attacking Kenya’s financial and communications system. But the evidence looks thin.

“At the time of the arrest, the police seized powerful telecommunications equipment,” the investigating officer said in an affidavit two weeks after the group’s arrest, according to court files. That equipment consisted of a handful of routers and laptops, two iPads, and 42 mobile phones—one for each person, according to Kibera Maina, the defense lawyer for Luo’s house—and there wasn’t even an internet connection set up. A forensics report on the phones and laptops recovered was inconclusive, making allegations of money laundering and other cyber scams unlikely.

The trial has dragged on in confused fits and starts. Hearings have been delayed by things like a lack of a translator and a witness that failed to show up. Luo and his peers know almost no one in Kenya, and, unable to speak English or Kiswahili, they can’t follow the court proceedings; only weeks after they were arrested did they even understand the charges. “I see them as victims themselves,” says Irene Wong, the pastor’s wife, who has been visiting the 12 women of the group in jail.

Concern in Nairobi’s Chinatown

It’s hard not to see the arrest of the 77 as part of a backlash against Kenya’s growing Chinese community.

For most Chinese living in Kenya, life has been easy. Nairobi is home to a network of Chinese-run restaurants, shops, churches, hotels, car garages, and more. The Chinese have mostly blended into the fabric of the city—a mixed group of shop owners, families, young professionals, recent graduates from some of China’s top universities, volunteers, and entrepreneurs, as well as the many staff of large state-owned Chinese firms.

Most Nairobians can point out the city’s major Chinese-built infrastructure: a ring of highways to lessen the notorious traffic, skyscrapers that will be some of Africa’s tallest, and the football stadium that president Barack Obama spoke from when he visited in July. Chinese companies are building everything from a standard-gauge railway between Nairobi and the port city of Mombasa—the country’s largest infrastructure project since the 1960s—to the capital city’s most expensive apartment complex. As much as a quarter of Kenya’s merchandise imports come from China, and China’s embassy in Nairobi is the largest Chinese embassy in Africa.

But as more Chinese move to Kenya, more Kenyans are unsure of their presence. “The Chinese are in this in-between place between ‘migrants’… and ‘expats’. They occupy this middle space both in terms of social standing and duration of stay,” says Hannah Postel, a migration researcher with the Center for Global Development, who previously studied Chinese migrants in Zambia. “My sense is that the locals don’t know where to place them in the hierarchy.”

Chinese companies have been criticized for breaking local labor laws, unfairly outcompeting Kenyan businesses, and contributing to crime in the country. In 2012, Kenyan traders protested what they called “the infiltration” of Chinese hawkers, chanting during a rally, ”Chinese go home.” A year later, Kenya’s National Intelligence Service wrote that “improved ties with China” might worsen unemployment, as Chinese immigrants took jobs that “should be preserved for Kenyans” like small-scale retail and the hospitality business.

The arrest of the 77 Chinese alleged hackers also came amid several recent cases of Chinese behaving badly in Kenya. Earlier this year, a Chinese restaurant owner came under fire for barring African patrons after 5pm. There have been several cases of Chinese nationals smuggling ivory, and Chinese workers have been credited with a surge in prostitution.

The Chinese are also seen as complicit with the corruption that pervades the Kenyan bureaucracy: two managers at the state-owned China Road and Bridge Group are being investigated for allegedly bribing highway officials to get around fines on overloaded trucks. Even the disappearance of stray dogs has been blamed on the Chinese and their dietary habits.

Across the continent, there have been other cases of growing mistrust toward the Chinese. Clashes between Zambian workers and Chinese managers have been documented for years—in October, three Chinese nationals working for a Chinese company in Kitwe were killed by unknown attackers. In Ghana, about 200 Chinese miners were attacked and deported last year.

No help from China

Since their arrest, Luo and his fellow prisoners have been pretty much abandoned by their compatriots. No Chinese diplomats or residents in Kenya—apart from a few local Chinese businessmen—have rallied to their side. Nor have international NGOs. They rely on family members at home to send money for legal fees and food. The Chinese embassy sends a representative and lawyer to each hearing, but has not gotten involved, aside from requesting that they be sent back to China once the verdict is made.

At home, what little attention the case has elicited has been negative. “The reason why Chinese people don’t have respect or status around the world is because of garbage like these guys,” a blogger commented in response to news of their arrest last December. “These Chinese have disgraced their country. They should get the death penalty,” another said.

The 77 may well, in fact, have been the victims of other Chinese. According to Chinese media, a Taiwanese syndicate responsible for scams targeting mainland Chinese may have recruited the group to work in Africa. The head of the operation is believed to have quickly left Kenya after their arrest.

Such cases are becoming increasingly common as the lure of Africa grows. Chinese workers are recruited to come over, but once they arrive, their passports are taken and they find themselves working illegally, without pay or for far less than they were promised. The embassy knows about such cases, but has few resources to police them. ”The Chinese government is not experienced enough in governing those overseas,” says Li Anshan, a professor of Chinese relations with Africa and the Middle East at Peking University.

The Chinese authorities’ reticence may also be because the case has become a test of how equal China and Kenya are in their newfound friendship. Last year, a Kenyan woman was sentenced to death in China for possessing a kilogram of cocaine. Pleas from her family and a social media campaign were ineffectual and turned attention on the Kenyan government’s dependence on China.

Prosecutors say that politics has nothing to do with the case. “They have broken our laws and need to be charged. It’s not just setting an example. It would be the same if they were Kenyans. It’s because there is evidence,” says Daniel Karuri, head prosecutor of the case. The Chinese embassy did not respond to requests from Quartz for official comment but emailed a statement they made last year. “It has been our consistent stand to protect lawful rights of Chinese citizens overseas, keep reminding them to strictly abide by local laws and regulations, while taking firm attitude on not being indulgent toward their illegal activities,” it said.

In the Chinese community in Kenya, people worry cases like this will make them more of a target. The manager of a Sichuanese restaurant in the Nairobi neighborhood of Westlands says that she suffered a big drop in business after the incident of another restaurant banning Kenyan diners. Already, some feel the police harass them for bribes. Others complain that visas have become harder to get.

In prison, the women spend their days writing letters to their boyfriends and husbands in the other detention center. The men buy sweatshirts and sweaters from locals to send to the women to keep them warm.

Luo says some of them have learned a little bit of English. He is impatient to go home and see his wife and son, who just turned two. His goals are simple now. “To go home as soon as possible, find a good job, raise the kids, and care for my parents,” he says. How has his impression of Kenya and Kenyan people changed since this experience? “I didn’t get a chance to meet many of them, so I don’t know.”