Several decades before he became the father of industrial design, Raymond Loewy boarded the SS France in 1919 to sail across the Atlantic from his devastated continent to the United States. The influenza pandemic had taken his mother and father, and his service in the French army was over. At the age of 25, Loewy was looking to start fresh in New York, perhaps, he thought, as an electrical engineer. When he reached Manhattan, his older brother Maximilian picked him up in a taxi. They drove straight to 120 Broadway, one of New York City’s largest neoclassical skyscrapers, with two connected towers that ascended from a shared base like a giant tuning fork. Loewy rode the elevator to the observatory platform, 40 stories up, and looked out across the island.

“New York was throbbing at our feet in the crisp autumn light,” Loewy recalled in his 1951 memoir. “I was fascinated by the murmur of the great city.” But upon closer examination, he was crestfallen. In France, he had imagined an elegant, stylish place, filled with slender and simple shapes. The city that now unfurled beneath him, however, was a grungy product of the machine age—“bulky, noisy, and complicated. It was a disappointment.”

The world below would soon match his dreamy vision. Loewy would do more than almost any person in the 20th century to shape the aesthetic of American culture. His firm designed mid-century icons like the Exxon logo, the Lucky Strike pack, and the Greyhound bus. He designed International Harvester tractors that farmed the Great Plains, merchandise racks at Lucky Stores supermarkets that displayed produce, Frigidaire ovens that cooked meals, and Singer vacuum cleaners that ingested the crumbs of dinner. Loewy’s Starliner Coupé from the early 1950s—nicknamed the “Loewy Coupé”—is still one of the most influential automotive designs of the 20th century. The famous blue nose of Air Force One? That was Loewy’s touch, too. After complaining to his friend, a White House aide, that the commander in chief’s airplane looked “gaudy,” he spent several hours on the floor of the Oval Office cutting up blue-colored paper shapes with President Kennedy before settling on the design that still adorns America’s best-known plane. “Loewy,” wrote Cosmopolitan magazine in 1950, “has probably affected the daily life of more Americans than any man of his time.”

But when he arrived in Manhattan, U.S. companies did not yet worship at the altars of style and elegance. That era’s capitalists were monotheistic: Efficiency was their only god. American factories—with their electricity, assembly lines, and scientifically calibrated workflow—produced an unprecedented supply of cheap goods by the 1920s, and it became clear that factories could make more than consumers naturally wanted. It took executives like Alfred Sloan, the CEO of General Motors, to see that by, say, changing a car’s style and color every year, consumers might be trained to crave new versions of the same product. To sell more stuff, American industrialists needed to work hand in hand with artists to make new products beautiful—even “cool.”

Loewy had an uncanny sense of how to make things fashionable. He believed that consumers are torn between two opposing forces: neophilia, a curiosity about new things; and neophobia, a fear of anything too new. As a result, they gravitate to products that are bold, but instantly comprehensible. Loewy called his grand theory “Most Advanced Yet Acceptable”—maya. He said to sell something surprising, make it familiar; and to sell something familiar, make it surprising.

Why do people like what they like? It is one of the oldest questions of philosophy and aesthetics. Ancient thinkers inclined to mysticism proposed that a “golden ratio”—about 1.62 to 1, as in, for instance, the dimensions of a rectangle—could explain the visual perfection of objects like sunflowers and Greek temples. Other thinkers were deeply skeptical: David Hume, the 18th-century philosopher, considered the search for formulas to be absurd, because the perception of beauty was purely subjective, residing in individuals, not in the fabric of the universe. “To seek the real beauty, or real deformity,” he said, “is as fruitless an enquiry, as to pretend to ascertain the real sweet or real bitter.”

Over time, science took up the mystery. In the 1960s, the psychologist Robert Zajonc conducted a series of experiments where he showed subjects nonsense words, random shapes, and Chinese-like characters and asked them which they preferred. In study after study, people reliably gravitated toward the words and shapes they’d seen the most. Their preference was for familiarity.

This discovery was known as the “mere-exposure effect,” and it is one of the sturdiest findings in modern psychology. Across hundreds of studies and meta-studies, subjects around the world prefer familiar shapes, landscapes, consumer goods, songs, and human voices. People are even partial to the familiar version of the thing they should know best in the world: their own face. Because you and I are used to seeing our countenance in a mirror, studies show, we often prefer this reflection over the face we see in photographs. The preference for familiarity is so universal that some think it must be written into our genetic code. The evolutionary explanation for the mere-exposure effect would be simple: If you recognized an animal or plant, that meant it hadn’t killed you, at least not yet.

But the preference for familiarity has clear limits. People get tired of even their favorite songs and movies. They develop deep skepticism about overfamiliar buzzwords. In mere-exposure studies, the preference for familiar stimuli is attenuated or negated entirely when the participants realize they’re being repeatedly exposed to the same thing. For that reason, the power of familiarity seems to be strongest when a person isn’t expecting it.

The reverse is also true: A surprise seems to work best when it contains some element of familiarity. Consider the experience of Matt Ogle, who, for more than a decade, was obsessed with designing the perfect music-recommendation engine. His philosophy of music was that most people enjoy new songs, but they don’t enjoy the effort it takes to find them. When he joined Spotify, the music-streaming company, he helped build a product called Discover Weekly, a personalized list of 30 songs delivered every Monday to tens of million of users.

The original version of Discover Weekly was supposed to include only songs that users had never listened to before. But in its first internal test at Spotify, a bug in the algorithm let through songs that users had already heard. “Everyone reported it as a bug, and we fixed it so that every single song was totally new,” Ogle told me.

But after Ogle’s team fixed the bug, engagement with the playlist actually fell. “It turns out having a bit of familiarity bred trust, especially for first-time users,” he said. “If we make a new playlist for you and there’s not a single thing for you to hook onto or recognize—to go, ‘Oh yeah, that’s a good call!’—it’s completely intimidating and people don’t engage.” It turned out that the original bug was an essential feature: Discover Weekly was a more appealing product when it had even one familiar band or song.

Several years ago, Paul Hekkert, a professor of industrial design and psychology at Delft University of Technology, in the Netherlands, received a grant to develop a theory of aesthetics and taste. On the one hand, Hekkert told me, humans seek familiarity, because it makes them feel safe. On the other hand, people are charged by the thrill of a challenge, powered by a pioneer lust. This battle between familiarity and discovery affects us “on every level,” Hekkert says—not just our preferences for pictures and songs, but also our preferences for ideas and even people. “When we started [our research], we didn’t even know about Raymond Loewy’s theory,” Hekkert told me. “It was only later that somebody told us that our conclusions had already been reached by a famous industrial designer, and it was called maya.”

Raymond Loewy’s aesthetic was proudly populist. “One should design for the advantage of the largest mass of people,” he said. He understood that this meant designing with a sense of familiarity in mind.

In 1932, Loewy met for the first time with the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Locomotive design at the time hadn’t advanced much beyond Thomas the Tank Engine—pronounced chimneys, round faces, and exposed wheels. Loewy imagined something far sleeker—a single smooth shell, the shape of a bullet. His first designs met with considerable skepticism, but Loewy was undaunted. “I knew it would never be considered,” he later wrote of his bold proposal, “but repeated exposure of railroad people to this kind of advanced, unexpected stuff had a beneficial effect. It gradually conditioned them to accept more progressive designs.”

To acquaint himself with the deficiencies of Pennsylvania Railroad trains, Loewy traveled hundreds of miles on the speeding locomotives. He tested air turbulence with engineers and interviewed crew members about the shortage of toilets. A great industrial designer, it turns out, needs to be an anthropologist first and an artist second: Loewy studied how people lived and how machines worked, and then he offered new, beautiful designs that piggybacked on engineers’ tastes and consumers’ habits.

Soon after his first meeting with the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Loewy helped the company design the GG-1, an electric locomotive covered in a single welded-steel plate. Loewy’s suggestion to cover the chassis in a seamless metallic coat was revolutionary in the 1930s. But he eventually persuaded executives to accept his lean and aerodynamic vision, which soon became the standard design of modern trains. What was once radical had become maya, and what was once maya has today become the unremarkable standard.

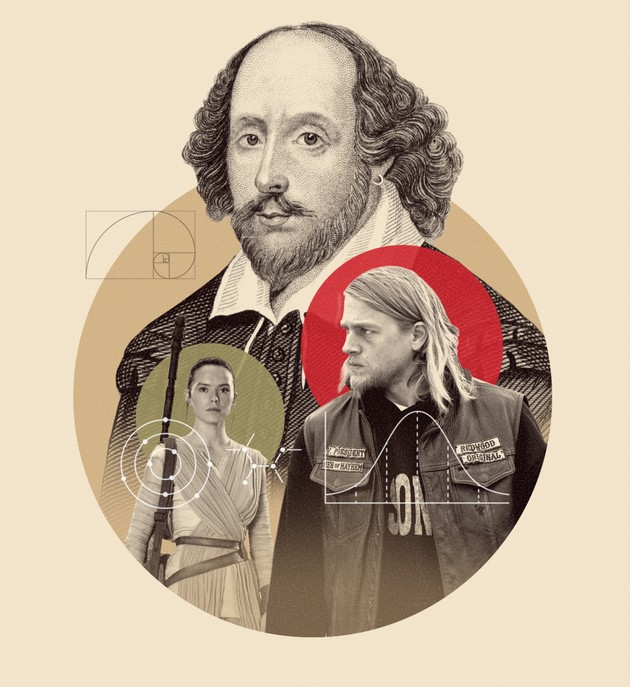

Could Loewy’s MAYA theory double as cultural criticism? A common complaint about modern pop culture is that it has devolved into an orgy of familiarity. In her 2013 memoir cum cultural critique, Sleepless in Hollywood, the producer Lynda Obst mourned what she saw as cult worship of “pre-awareness” in the film and television industry. As the number of movies and television shows being produced each year has grown, risk-averse producers have relied heavily on films with characters and plots that audiences already know. Indeed, in 15 of the past 16 years, the highest-grossing movie in America has been a sequel of a previously successful movie (for example, Star Wars: The Force Awakens) or an adaptation of a previously successful book (The Grinch). The hit-making formula in Hollywood today seems to be built on infinitely recurring, self-sustaining loops of familiarity, like the Marvel comic universe, which thrives by interweaving movie franchises and TV spin-offs.

But perhaps the most maya-esque entertainment strategy can be found on award-winning cable television. In the past decade, the cable network FX has arguably produced the deepest lineup of prestige dramas and critically acclaimed comedies on television, including American Horror Story, The Americans, Sons of Anarchy, and Archer. The ideal FX show is a character-driven journey in which old stories wear new costumes, says Nicole Clemens, the executive vice president for series development at the network. In Sons of Anarchy, the popular drama about an outlaw motorcycle club, “you think it’s this super-über-macho motorcycle show, but it’s also a soap with handsome guys, and the plot is basically Hamlet,” she told me. In The Americans, a series about Soviet agents posing as a married couple in the United States, “the spy genre has been subverted to tell a classic story about marriage.” These are not Marvel’s infinity loops of sequels, which forge new installments of old stories. They are more like narrative Trojan horses, in which new characters are vessels containing classic themes—surprise serving as a doorway to the feeling of familiarity, an aesthetic aha.

The power of these eureka moments isn’t bound to arts and culture. It’s a force in the academic world as well. Scientists and philosophers are exquisitely sensitive to the advantage of ideas that already enjoy broad familiarity. Max Planck, the theoretical physicist who helped lay the groundwork for quantum theory, said that “a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

In 2014, a team of researchers from Harvard University and Northeastern University wanted to know exactly what sorts of proposals were most likely to win funding from prestigious institutions such as the National Institutes of Health—safely familiar proposals, or extremely novel ones? They prepared about 150 research proposals and gave each one a novelty score. Then they recruited 142 world-class scientists to evaluate the projects.

The most-novel proposals got the worst ratings. Exceedingly familiar proposals fared a bit better, but they still received low scores. “Everyone dislikes novelty,” Karim Lakhani, a co-author, explained to me, and “experts tend to be overcritical of proposals in their own domain.” The highest evaluation scores went to submissions that were deemed slightly new. There is an “optimal newness” for ideas, Lakhani said—advanced yet acceptable.

This appetite for “optimal newness” applies to other industries, too. In Silicon Valley, where venture capitalists also sift through a surfeit of proposals, many new ideas are promoted as a fresh spin on familiar successes. The home-rental company Airbnb was once called “eBay for homes.” The on-demand car-service companies Uber and Lyft were once considered “Airbnb for cars.” When Uber took off, new start-ups began branding themselves “Uber for [anything].”

But the preference for “optimal newness” doesn’t apply just to academics and venture capitalists. According to Stanley Lieberson, a sociologist at Harvard, it’s a powerful force in the evolution of our own identities. Take the popularity of baby names. Most parents prefer first names for their children that are common but not too common, optimally differentiated from other children’s names.

This helps explain how names fall in and out of fashion, even though, unlike almost every other cultural product, they are not driven by price or advertising. Samantha was the 26th-most-popular name in the 1980s. This level of popularity was pleasing to so many parents that 224,000 baby girls were named Samantha in the 1990s, making it the decade’s fifth-most-popular name for girls. But at this level of popularity, the name appealed mostly to the minority of adults who actively sought out common names. And so the number of babies named Samantha has collapsed, falling by 80 percent since the 1990s.

Most interesting of all is Lieberson’s analysis of the evolution of popular names for black baby girls starting with the prefix La. Beginning in 1967, eight distinct La names cracked the national top 50, in this sequence: Latonya, Latanya, Latasha, Latoya, Latrice, Lakeisha, Lakisha, and Latisha. The orderliness of this evolution is astonishing. The step between Latonya and Latanya is one different vowel; from Latonya to Latoya is the loss of the n; from Lakeisha to Lakisha is the loss of the e; and from Lakisha to Latisha is one consonant change. It’s a perfect illustration of the principle that people gravitate to new things with familiar roots. This is how culture evolves—in small steps that from afar might seem like giant leaps.

In a popular online video called “4 Chords,” which has more than 30 million views, the musical-comedy group the Axis of Awesome cycles through dozens of songs built on the same chord progression: I–V–vi–IV. It provides the backbone of dozens of classics, including oldies (the Beatles’ “Let It Be”), karaoke-pop songs (Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’ ”), country sing-along anthems (John Denver’s “Take Me Home, Country Roads”), animated-musical ballads (The Lion King’s “Can You Feel the Love Tonight?”), and reggae tunes (Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry”).

Several music critics have used videos like “4 Chords” to argue that pop music is derivative. But I think Raymond Loewy would disagree with this critique, for two reasons. First, it’s simply wrong to say that all I–V–vi–IV songs sound the same. “Don’t Stop Believin’ ” and “No Woman, No Cry” don’t sound anything alike. Second, if the purpose of music is to move people, and people are moved by that which is sneakily familiar, then musicians—like architects, product designers, scholars, and any other creative people who think their ideas deserve an audience—should aspire to a blend of originality and derivation. These songwriters aren’t retracing one another’s steps. They’re more like clever cartographers given an enormous map, each plotting new routes to the same location.

One of Loewy’s final assignments as an industrial designer was to add an element of familiarity to a truly novel invention: nasa’s first space station. Loewy and his firm conducted extensive habitability studies and found subtle ways to make the outer-space living quarters feel more like terrestrial houses—so astronauts “could live more comfortably in more familiar surroundings while in deep space in exotic conditions,” he said. But his most profound contribution to the space station was his insistence that nasa install a viewing portal of Earth. Today, tens of millions of people have seen this small detail in films about astronauts. It is hard to imagine a more perfect manifestation of maya: a window to a new world can also show you home.

This article is adapted from Derek Thompson’s forthcoming book, Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction.