This splendid book by a young American Jewish scholar is the product of an early emotional and intellectual transformation.

Seth Anziska was “raised with a strong attachment to Zionism” and sent to a yeshiva in Gush Etzion when he was 18. Gush Etzion was the site of a kibbutz founded before the Israeli war of independence. In 1948 it fell under Jordanian control, and it remained part of the Hashemite Kingdom until Israel conquered the West Bank in the six-day war of 1967.

Anziska’s arrival in 2001 coincided with the height of the second intifada. The image he had cultivated of biblical Israel from the distance of New York City was shattered by bus rides through the West Bank.

“With the overwhelming obsession over the land of Israel,” he writes, “no one seemed to take much notice of the non-Jewish inhabitants living there. How could we not have seen them? Why were Palestinians unable to move freely, in the very same space where I, a US citizen, could come and go as I pleased? It seemed to me that the only difference was based on religion or ethnicity, one system for Jews and another for Arabs.”

In the years since, Anziska has encountered many other American Jews who have felt the same “incongruence and even self-deception that lies at the heart of discovering certain uncomfortable truths about the relationship between Israel and the Palestinians”.

For Anziska, these revelations led to a years-long investigation of the Camp David accords of 1978, the endless on-again, off-again negotiations that followed, and the Oslo accords of 1993. His combination of original research and personal fearlessness has produced one of the most compelling works of political and diplomatic history I have ever read.

Though he never mentions the organization, Anziska’s sensibility is very much that of J Street, “the political home of pro-Israel, pro-peace Americans” who believe in a two-state solution. But his judgments are so careful and nuanced that his book always reads like history, never propaganda.

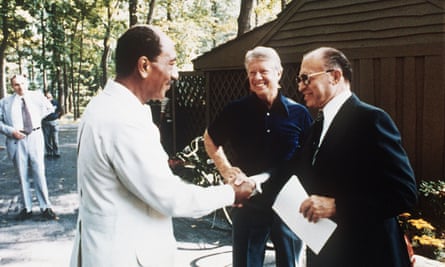

Preventing Palestine’s core argument is focused on the Camp David accords presided over by Jimmy Carter in 1978, which led the Israeli prime minister, Menachem Begin, to agree to relinquish the Sinai to Egypt, in exchange for Egyptian president Anwar al-Sadat’s promise to end the state of war and recognize the state of Israel.

This was widely seen as both a great triumph for Carter and the single greatest leap toward peace in the Middle East since the end of the six-day war.

Anziska has a different view. He finds the roots of the decades-long standoff that followed Camp David in Sadat’s preoccupation with regaining the Sinai, which allowed Begin to accelerate the settlements of the West Bank, a process which has continued unabated. He thinks the Egyptian president’s willingness to negotiate over the amorphous goal of Palestinian “autonomy” is at the heart of the stalemate which has prevailed.

He writes: “The very idiom in which early negotiations were rooted – autonomy not sovereignty, limited self-rule – exacerbated conditions on the ground and dismantled the political mechanisms for a just resolution of the Palestinian question.”

Sadat’s trip to Jerusalem was viewed in the US as a huge gamble for peace. But Anziska believes it was also the beginning of the end for Palestinian independence. Begin’s determination to build more settlements “would have been impossible without the concessions” of Sadat, he writes, and the settlements became “the mirror and negation … to the possibility of Palestinian sovereignty”. In 1977, there were about 4,000 Jewish settlers in the West Bank and Gaza. By 1992, on the eve of Oslo, there were more than 100,000.

A particularly important section of the book deals with the Israeli invasion of Lebanon 1982 and its catastrophic consequences. The defense minister, Ariel Sharon, believed “the lack of a diplomatic solution to the Palestinian question after the Camp David Accords invited a display of force that would somehow defeat Palestinians in their Lebanese stronghold”. He thought he could “destroy the PLO military infrastructure throughout Lebanon and undermine the organization as a political entity, in order to ‘break the backbone of Palestinian nationalism’ and facilitate the absorption of the West Bank by Israel”.

Anziska found proof in the notebooks of the state department official Charles Hill that the secretary of state, Alexander Haig, effectively gave Sharon the green light: “We can’t tell you not to defend your interests. But we are living with perception. Must be a recognizable provocation.”

The invasion led to the Sabra and Shatila massacre by Christian Phalange militiamen who “raped, killed and dismembered at least 800 women, children and elderly men while Israeli flares illuminated the camps’ narrow and darkened alleyways”.

To Anziska, the invasion was “both a moral stain and a strategic disaster, undercutting US influence in the region and precipitating further military involvement in the Lebanese civil war”. A document he discovered, he wrote this week in the New York Review of Books, “demonstrated how the slaughter of civilians in the Palestinian refugee camps of south Beirut was prolonged” by Morris Draper, an American diplomat who acquiesced in “Sharon’s “deceptive claim of ‘terrorists’ remaining behind”.

Anziska quotes the Israeli intellectual Amos Oz: “After Lebanon, we can no longer ignore the monster, even when it is dormant, or half-asleep, or when it peers out from behind the lunatic fringe … It dwells, drowsing, virtually everywhere … even in our soul-melodies.”

Anziska has made a major contribution to the history of this conflict. As the Trump administration repeats the errors of so many predecessors, with moves to delegitimize and defund the PLO, Anziska reminds us that America has always shared responsibility for the lopsided competition between Israel and the Palestinians.

“The contest,” he writes, “… was generally resolved in favor of the side that could better withstand its own Pyrrhic victory at any given moment.”

That side has almost always been Israel. The US has been complicit in far too many of those useless “victories”.