In his native Detroit, Jack White—White Stripes frontman and one of the most active and influential musicians of the last twenty years—has built a beautiful, efficient, and fully staffed record manufacturing plant. Why? Because records are better.

FRIDAY

Outside the Third Man Records storefront on Detroit's long, lonely Cass Corridor, a line of tents, sleeping bags, and lawn chairs stretches fifty yards. Many of the people who crawl in and out of the tents and who sit in the lawn chairs wear shirts bearing the logo of Third Man Records, the independent label founded by Jack White, frontman of The White Stripes, the band that emerged from this very neighborhood. The men have hip beards and the women wear flannel and beanies—it's cold, Detroit in February. Some rub sleep from their eyes even though it's three in the afternoon. The reason they're here is that Third Man is opening a new venture: Third Man Pressing, a record factory. The opening will include concerts, and tours, and special colored editions of albums that will never be available again. But the opening is on Saturday, and this is Friday afternoon, and it is cold, and a storm is rolling in.

Inside, on a wall in the back office, is a yellow and black map of the world. The labels on it are not the usual labels. Where it ought to say "United States," it says "Concrete." Northern Africa says "Sand." The Pacific Ocean: "Water." The Southern Ocean: "Colder Water." A legend in the southwest corner explains: "We have avoided most political and cultural names and labels since they change frequently throughout history: i.e., if a location has sand, it will probably have sand longer than this map will exist, but how long will a place be called 'Russia,' for instance?"

If you could zoom in on the Detroit of forty years ago, it would have said "Autos." Now, who knows? Later tonight, Jack White will plant a flag in this corner of his hometown, and the flag will read "Vinyl."

"I think a lot of people think, oh, you're a Luddite, or you live in the past, or this is nostalgia or golden-age thinking, all that," White says of his plans for Third Man Pressing. He's on a couch under the map, wearing a yellow jacket and black shoes. His black hair is parted down the middle, longer in front than in back, and he occasionally reaches up to do the opposite of smoothing. "I disagree. I like to take what's beautiful about what's already been proven—what works—and ask, how can we marriage that with what's happening right now? And what can we do with that tomorrow?"

Tomorrow is the grand opening for the public, but tonight is the VIP party for the industry. Third Man has invited executives from every other record plant in the country. As vinyl has made its comeback over the past few years, pressing plants have tried to keep up with old equipment held together with salvaged parts and tinkering. But Third Man found a company making new presses, and they bought eight of them—enough to make five thousand records in an eight-hour shift. Tonight as those executives gather—with friends and family of Third Man, music-business people, and Detroit people—the new presses will be running.

White says Third Man is entering the lineage of what he calls "ancient technology," pointing out that records were originally made of shellac, a substance humans have been using for thousands of years. "You gotta understand," he says. "When you're a musician and you started entering the late '90s and the early 2000s, things became more and more digital, and it started to seem like—whether it was blues, jazz, or rock and roll, whatever genre you were involved in—you kind of felt like the world around you was dying in a big way."

Records are analog, meaning the mechanisms that make sound exactly mimic the original recording. Digital sound files are actually collections of discrete sounds that, played in sequence, approximate music, like a flipbook for the ear. On an average CD, there are 44,100 of these individual sounds in every second of a song. That is a lot, but it also means there are 44,099 gaps. There's something missing.

To Jack White, this is an acute condition. Technologies come and they go, replaced by something cheaper and faster. But what if the old technology—the slower, more expensive one—is better? What if it's worth preserving, even if preserving it won't stop the forward march of the new stuff? What if it's still relevant? You can complain about the new technology, and you can reminisce about the old. You could write an op-ed. But is there anything a person can do to stop, or at least slow, a cultural shift? If you're a person who cares, and who has means, and, in this case, who has some fame, what exactly can you do to maintain quality in a world that seems to care about it less and less?

Around 8 p.m., guests begin to arrive, come to witness the latest proof that you can still make things in Detroit. It's colder and a little wet out, and the tent city is now fronted by a valet kiosk, and the guests are dressed semiformal. Tonight Third Man Records welcomes Third Man Pressing. Inside, you first walk through the record store. Then you worm through the thick crowd near the concert stage where the Craig Brown Band is playing. Finally you find yourself in the factory itself, where, amidst high-tops and bottomless craft cocktails, workers in black and yellow jumpsuits man the presses. The point White seems to be making is this: Music is made and sold by people, yet the transformation of music into vinyl—the step of making the invisible visible—is done by people who have been made largely invisible. This thing Jack White is talking about, about things dying, or disappearing, is not just about music.

And then there is Jack White himself! Now in a black suit and a yellow tie, he makes a toast to craftsmen: "Thanks to everyone here. The carpenters, the plumbers, everyone who worked on every pipe. Every painter. Everyone who worked on every inch of this place . . ." Clapping, heartily, everyone. The older men—must be record executives or scions of the city—wearing suits that have never been in style; the middle-aged rockers who are still more stylish than the average non-cool person; and the younger musicians, who will always be the coolest people in the room. Well, except maybe for the people actually running the presses because, hot damn, they're making records, the ones you can buy right now if you want—something White pointed out earlier has never been done before: records coming off the presses and being made available straightaway to music fans.

The party is all drinking and revelry until rumor spreads around midnight that someone has been struck by lightning. Paramedics appear. The crowd coils up tight like a mainspring. Even White is caught up. "I think someone was struck by lightning!" he says. Then, ever the host, "Hey—meet my brother Eddie!" It's all a blur. No one can tell if someone was actually struck by lightning, or if it's the affair itself, the fact that, yup, there are sudden fissures opening up the sky and letting out the rain and everyone has had a few too many drinks and the band is hot and the floor in the plant is yellow like the fissures. But this much is certain: What midnight means is that the folks outside are now less than twelve hours from their own celebration, and they are wet and tired but no less electrified than anybody else.

SATURDAY

Now the people are lined up around the side of the building. Not out front, but beside the pizza place next door, past the painted Willys-Overland badge—the ur-Jeeps were once made in this building—outside the loading dock. Inside, Third Man employees—black button-downs and yellow ties for the men, yellow and black dresses for the women—let them in in groups. Tour groups.

The factory workers are on display again, running their vinyl presses and extruders, the latter of which look something like hot-glue guns sized up for a Pink Floyd concert stage. There's one extruder and two presses for every worker. The worker scoops vinyl pellets from a fifty-five-gallon drum and dumps them into a hopper on the extruder. The extruder melts them down and pushes a snake of hot vinyl out the nozzle and into a receptacle that coils it into a puck. The open jaws of the press hold a stamper plate for each side of the record, musical negatives that bear instead of grooves a spiraling mountain range of music. A worker deposits A-side and B-side labels into its maw, throws in the puck—at 300 degrees Fahrenheit—and the jaws clamp down and retract into the body of the machine, where a cycle of hot and cold makes the vinyl alternately pliable and rigid, until it is a record. Eddie Gillis—one of White's six brothers—and Brandon Chrzanowski, the plastics expert Third Man brought in to help run the plant, call the production of a perfect plastic disc a war against heat and time.

Third Man's artillery is made by a small German company of music industry veterans who used to make records but, like everyone else, gave it up as CDs and MP3s took over. Their company is called Newbilt because the machines are a modern take on a classic press called Finebilt that was manufactured in Los Angeles in the 1950s and '60s. They've got electronic controls and sophisticated hydraulics, but in one notable way, the machines are old- fashioned: They're manual. There is a worker at every one pulling pucks into presses and turning out records. A few other companies have recently started making presses, and some are robotic. Third Man wanted manual machines. They wanted to create jobs—Third Man Pressing has created twenty jobs—and they valued creativity. (Over the last decade they've released a liquid-filled record, a twelve-inch single with a seven-inch single hidden inside it, and launched a record player into space while it played a vinyl of music from Carl Sagan's "Cosmos." In 2014, White released his last solo album, Lazaretto. Third Man called the release an Ultra LP, which means that they'd crammed every possible version of vinyl sound reproduction onto one record: songs played at three different speeds, songs were hidden underneath the labels. One song had an acoustic or electric opening depending where you dropped the needle.)

In a little room off the factory floor and off the tour, there's a massive mixing board and a giant lathe that cuts acetates, the original documents from which records are made. This lathe and this mixing board are tied to the concert stage in the record store, right now playing host to a band called The Mummies. The little room lets live shows be cut directly to acetate, only a few hundred feet away.

The tour groups don't see all of this, but what they do see, what Third Man makes sure they see, are the possibilities. A display in front of the presses shows different colors of vinyl pellets, sitting like Nerds candy in ramekins, and the records they could become. One, pieced together with quadrants of four different pucks, has come out looking like the game Simon. Another, yellow, with red pellets thrown in at the last minute, has an ethereal haze of red over its cheery face, something like a solar flare, or the finish on a sunburst Telecaster.

SUNDAY

9 A.M. Eddie is draining hot purple vinyl from an extruder. The purple is from a special-edition Destroy All Monsters/Xanadu split LP they were making on opening night, but now Eddie prepares to load black record seeds into its hopper.

"When we had all the people here from the major plants the other night, if a bomb had gone off, it would have really put a dent in the pressing business," Eddie says.

At 10 a.m. four guys in Third Man Pressing jumpsuits walk in. Someone turns on Detroit Gospel Reissue Project #2, a record they've just started to press. It's a sleepy morning. Two guys sit down in the quality-control area, where they pull records off spindles one at a time to examine them for defects. The other two head to pressing stations.

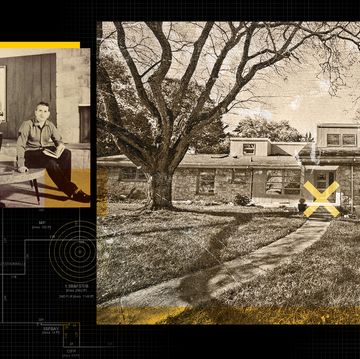

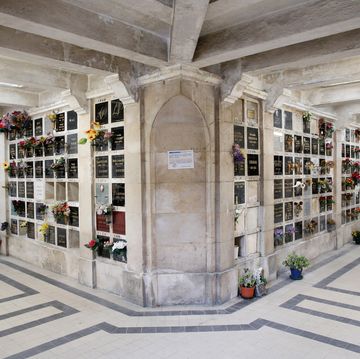

When Third Man bought the plant in 2015, it was a disused parking garage with a few fluorescent lights, a leaky roof, and a lot of rust. Third Man has since made a sizeable investment in its transformation. Third Man brought in gas. Third Man brought in electric. Third Man brought in sewer. Then White applied a color scheme. The concrete floor is a spit-shined sunflower yellow. The structural support pillars and ductwork are red. There's a tool chest against one wall: yellow DeWalt. Here and there are green accents: doors, cabinetry, and wheeled carts that hold the black metal drums of vinyl pellets, which have "Record Seeds" stenciled on their sides in white.

This is what you do when you want to preserve a technology you believe is still relevant. You build a temple to it, and you paint it bright, and you invite everybody.

Jack White wears black pants, a black shirt, a black Cass Corridor letterman jacket. He is having his picture taken. He's brought his mother—eighty-six, and word was she was at the after-party on Friday until 3 a.m.—and Stephen, another brother.

As the presses fall into a rhythm, somebody changes the music. Cabbage Alley, by The Meters. The tempo picks up. Eddie shifts to QC, where he holds records up to the light like hundred-dollar bills and looks them down sidelong like a hustler checking a pool cue. Someone changes the music again. Wild Horses Rock Steady, Johnny Hammond. A jazz album.

White admires the operation, basks in it, puts it through its paces for the shoot. First there are shots before the stamper library, a ceiling-height green bookcase where Third Man stores plates off the presses for reference. Then to the boiler room, where water for the presses' heat cycle is warmed. Then to the listening station, where the QC team has a guy listen to new records to make sure they sound pristine and warm to the ears.

White talks to the guys on the presses, walks the floors. His mother asks if he smiled in the pictures, for once. Behind a black curtain, through a large glass window, are the people. The people who've been here all weekend, and who will keep coming, in part to look through this window. It was White's idea to give the public a view. Some of the guys here have taken to calling it the aquarium. Every day, as the record store opens and fills, faces appear and swim behind it. Young Detroiters. A balding middle-aged guy in a Bob Seger System baseball tee. Women old enough to make you wonder if maybe they were on the Cass Corridor years ago and used to catch The White Stripes at the Gold Dollar.

FRIDAY

Before the party, White says something that foreshadows the Sunday-morning march of the tourists. He grabs a yellow notebook and a black pen and draws a long, straight line. "This is analog, you know? A pencil goes on a paper and it drags. This is analog, whether it's tape or vinyl," he says. Then he resets the pen atop the paper and draws a parallel dotted line. "And this is digital. No matter how good your sample rate, you've got breaks." He looks at the two lines. "And this"—here he points at the solid line, and stutters out a laugh—"This is, kind of: real life. No breaks. No empty spaces in between."

Some of the workers were worried they'd feel like monkeys at the zoo with the window, but they haven't. Because while they are ostensibly the ones inside the aquarium, from their vantage point they have the rare gift of being able to discern something profound in the faces of the people through the glass, whose brows furrow in consideration, whose eyes gleam in recognition that the presses are not far removed from the preschool impulse to jam Play-Doh against a zipper so you can see the imprint, whose mouths hang open and drip joy at the Technicolored reveries of a man who makes music made real. It is written on those faces: In real life, where there are no breaks, and no empty spaces, you are fortunate indeed that the fruit of your labor is something beautiful.

This story appears in the July/August 2017 issue.

Kevin is a writer and editor living in Brooklyn. In past lives he’s been an economist, computer salesman, mathematician, barista, and college football equipment manager.