The ambiance of the luxury suite on the 14th floor of the Wynn Hotel is at once both sybaritic—the remains of a generous lunch are visible piled on a large tray as I enter the door—and clinical, with an array of wires, patches, electrodes in evidence scattered on tables and other flat surfaces. It sets the tone pretty effectively for the demo I’m about to engage in: A sneak peek at Thync, a new technology that promises to help its users “conquer life” by allowing them to tweak and torque their mood on demand.

That puts Thync at the intersection of fantasy and science fiction. We’d all love quick and effective ways of amping up or chilling out, and of course, there are plenty of pharmaceutical methods to get that done. But they come with unintended consequences: Soar-and-crash rebound, nasty side effects and of course, the threat of addiction.

Though currently shy of FDA approval—the company expects to receive it by end of 2015—Thync claims that its tech has none of that baggage. And I and my colleague Andrew Hawn are about to find out how true that claim is for ourselves.

We’re ushered into a side room of the suite with a floor-to-ceiling picture window facing the surreal landscape of Vegas and seated in a pair of comfortable leather chairs. Shortly thereafter, we’re joined by Thync’s cofounders, CEO Isy Goldwasser, and Dr. Jamie Tyler, the startup’s chief scientific officer. They seat themselves on the bed and explain Thync’s story.

“We came here because we wanted people to experience the technology, but we’re not ready with a product and won’t be until sometime later in 2015,” explains Goldwasser. “But the tech is real. It’s rooted in real science. And we’ve done tests—thousands of tests—comparing what we’re doing with Thync to placebos, and three of four people have a definitely noticeable effect. And we’re still optimizing it to improve that ratio.”

Thync’s technology involves calculated stimulation—at present, via contact electrodes placed along the orbital ridge and the base of the neck—of cranial nerves, that is to say, nerves that travel directly into the brain as opposed to the spinal cord. The stimulus is currently applied through electricity; the company initially used ultrasound (which is capable of greater precision, “down to an area the size of an M&M,” says Goldwasser, and deeper travel—“directly into the brain itself”), but the unwieldy size of the technology made it impractical for how they imagined it being used. Which is to say, regularly and everywhere.

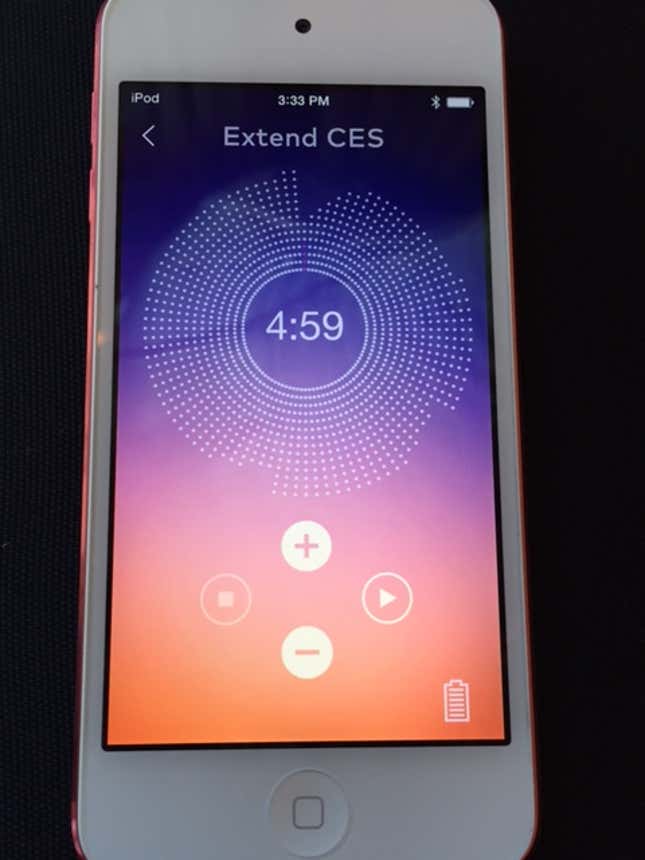

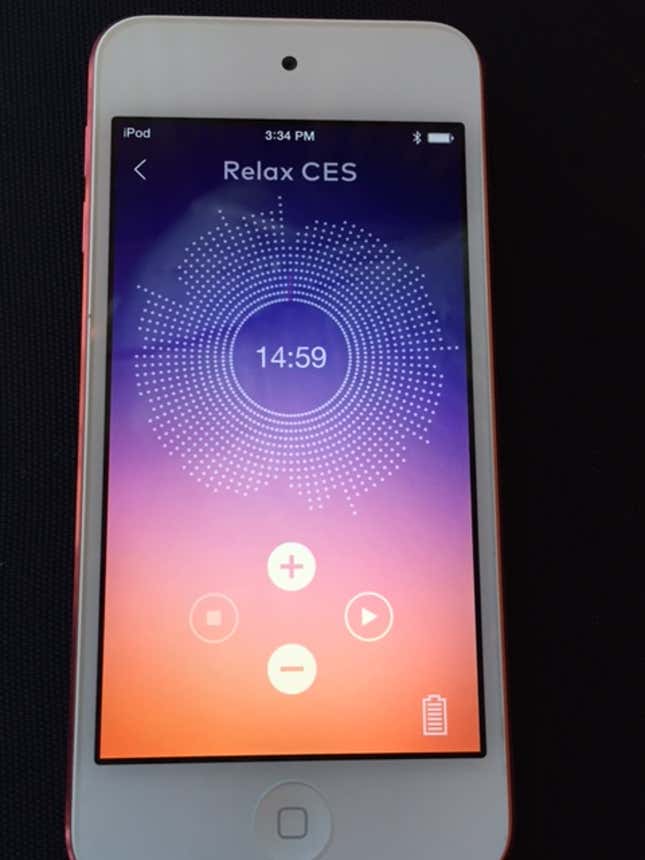

Because Thync is a wearable—perhaps the first wearable technology that actively does something to you rather than track what you’re doing to yourself. It sticks to your temple, a shaped, rounded triangle of plastic with a replaceable strip of flat printed-circuitry plastic that navigates the side of your head down to the base of your skull. The forehead and the neck piece generate impulses, controlled by the program you’ve loaded via a companion smartphone app, that actively jolt the neurons in those two sensitive areas; these programs generate mood shifts that Thync calls “Vibes.” At present, there are two sets of Vibes available: One designed to produce relaxation, and another designed to produce alertness.

Andrew is a chill Californian and I’m a hyper New Yorker. Naturally, he picks the “Calm” Vibe and I pick the “Energy” Vibe. By this time, Goldwasser and Tyler have left the room, replaced by staff researchers Jonathan Charlesworth and Alyssa Boasso, who fit us with our electrodes, and help us crank up our apps. Charlesworth jovially notes that the apps are set at 70% of full capacity, but that we have the freedom to manually crank up the setting to 100% with a swipe of our thumbs. “I’d get used to what 70% feels like first, but once you do, go for it,” he says.

I barely wait before jacking the setting to 100. There’s no point in experiencing something unless you’re doing it to the max. (Rock and roll!)

At 70, the sensation the device produces is like ants crawling on the surface of your skin. At 100, the ants are on the inside of your skin and dancing a wild myrmecoid folk dance.

Seeing me flinch involuntarily, Charlesworth points out the buttons that allow momentary “boosting” of the impulse on demand. I thumb a button and the ants suddenly seem to be attempting to make a beachhead on my prefrontal cortex. But the feeling quickly ebbs as my nerves adjust to the stimulus. It’s distracting, but readily bearable.

“We’ve capped it at what we think people will generally feel comfortable,” says Charlesworth, grinning. “To be fully honest, though, I do it at 120% every day.”

He’s not the only one. The Thync team eats its own dog food, from top to bottom. They’re true believers in the technology. So are investors like Khosla Ventures, who’ve backed it to the tune of a cool $13 million—indeed, one of their VCs happens to be hanging out at the suite at the same time we are, getting a de-stress Vibe to wind down from CES’s overcrowded excess. “How long have I been doing this?” he says, popping his head into the room, the electrodes still attached. “Man, I fell asleep.”

The answer: About half an hour. “We let you go long,” says Charlesworth. “Looked like you needed it.”

The 20 minutes are up sooner than I imagined. I peel the device from my forehead, remove the underlying disposable electrodes, replace my glasses. The difference, I must admit, is palpable: Everything seems more finely etched, crisper. I notice more details in the world around me, and the sense of dullness that three days spent listening to press pitches from moribund industry giants has draped over my brain seems to have been peeled away. Andrew’s experience is less dramatic—he says he definitely feels more relaxed, but you can’t get less anxiety than zero. The up elevator, meanwhile, doesn’t have the same ceiling.

Goldwasser is back. “How is it?” he asks. I tell him that I feel “overclocked,” and he laughs.

“There’s a whole biometric suite that we use to track people’s response to Thync, heartrate, galvanic response, and so on, but nothing so far has been as reliable as their actual experience,” he says. “How they describe it, how they rate it—that’s where we’re seeing the real results.”

Scientists accept that Thync’s effects are legit. “Thync has produced a technology considered impossible only a few years ago,” says City College of New York professor Dr. Marom Bikson, a leading expert in neural engineering and medical device design. “This platform shows tremendous promise.”

This promise was previewed in a 2011 segment on NPR’s terrific science show Radiolab, “Nine-Volt Nirvana,” in which New Scientist editor Sally Adee undergoes transcranial direct current stimulation—essentially the phenomenon Thync is utilizing—as an experiment in improving the capacity to learn. During the segment, in which Adee is subjected to TDCS under the auspices of DARPA-funded research, she is handed an M4 assault rifle and goes through a sniper exercise in which she has to pick off enemy targets while avoiding the harming of hostages. Before the volt jolt, she proves herself comically inept. Afterwards, she becomes a killing machine.

“We don’t yet have a commercially available ‘thinking cap’ but we will soon,” she notes in a blog post afterwards—written well before the introduction of Thync. “The research community has begun to ask: What are the ethics of battery-operated cognitive enhancement?… Is brain boosting a fair addition to the cognitive enhancement arms race? Will it create a Morlock/Eloi-like social divide where the rich can afford to be smarter and leave everyone else behind? Will Tiger Moms force their lazy kids to strap on a zappity helmet during piano practice?”

All good questions. And yet, at the end of her post, Adee notes that her experience with TDCS was so potent that, like the protagonist in the classic book Flowers for Algernon, as the effects wore off, she mourned the loss of the clarity and focus it gave her—with no evident downsides. “I hope you can sympathize with me when I tell you that the thing I wanted most acutely for the weeks following my experience was to go back and strap on those electrodes,” she wrote. “What would a world look like in which we all wore little tDCS headbands that would keep us in a primed, confident state, free of all doubts and fears? Wouldn’t you wear the shit out of that cap? I certainly would. I’d wear one at all times and have two in my backpack ready in case something happened to the first one.”

And that, in summation, is Thync: The first product to deliver TDCS to the masses, at a price they promise will be “affordable” and in a form-factor designed to be retail consumer friendly.

For about an hour after my 20-minute session—the Vibes are designed to last 60 to 90 minutes—I walk the floor without the irritation and sullenness that comes from dealing with CES’s massive herds of suits, neatly sidestepping people barreling at me while texting. I conduct an interview with an unnamed major smartphone brand that nearly turns into a consulting session, with them asking me more questions on the insights I’d had about their products than I asked them. I speak at a faster clip—but without slurring or slipping.

The feeling of sharpness and lucidity is one that I quickly miss. I have misgivings—the very fact that you long to be “up” once you’re down is a little scary, leading to fears that the product, though not physiologically addictive, might produce psychological addiction.

I already drink three cups of java a day—buckets really; at a friend’s place, I once mistook a white ceramic flower pot for a coffee mug and used it all morning before she pointed it out. Would Thync make me a wirehead, eager to feed sweet current into my brain to keep that sense of being “overclocked”?

In a post-session phone interview, Goldwasser is quick to challenge my fears. “Sure, we can come up with a lot of scenarios,” he says. “But we guide all our research by the goal of building products that allow people to do something positive for themselves. If it’s useful and beneficial, we develop it. If it’s unethical or dangerous, we don’t. You want to get focused, sleep more, socialize better, destress in a safe way? We’re here to help. If there’s a grey zone, we won’t go there.”

And given the world’s dependence on pharmacological means to get the same results, Thync is actually both safer and smarter.

“The potential for the technology is open ended,” he says. “Once we get this on the market, we’ll be able to keep adding Vibes over time—programs you can download to expand the product’s usefulness.”

Moods on demand. Pushbutton brain-boosts. Relaxation at the touch of a finger. As I head to the airport, I learn from my Twitter feed that Thync has won the Best at CES Award for “Cool Tech.” I also get a message from Thync reminding me that the next generation of the device should be ready in about a month—and that it will be vastly improved.

My neurons will be there when you are, Thync. To paraphrase the great Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard: I’m ready for my brain-up.