“We fight against the nude in painting, as nauseous and as tedious as adultery in literature,” proclaimed the Italian Futurists in 1910. The nude was dead; the speeding car more thrilling than the female body. Yet by 1919, Modigliani had almost single-handedly resuscitated her. This was not the decorous nakedness of Manet, the woman seen at a distance, wreathed in allegory. Neither was it the mutilating brutality of Picasso, whom Kenneth Clark saw as engaged in “a scarcely resolved struggle between love and hatred”. These were warm, living women, bursting out of the frame towards the viewer; women drifting languorously to sleep or writhing with pleasure. Naked flesh, captured on the canvas, would never be the same again.

For decades, every Modigliani book and exhibition has talked about the “myth” of Modigliani, and the upcoming retrospective at the Tate is no exception. Is the story I’ve just described part of the myth? It may be, but like every myth, it points to a truth: they are different; they did change everything. We couldn’t have the abstracted forms of Alfred Stieglitz or Edward Weston’s nude photographs without the influence of Modigliani. Without him, it might have been years before the nude became so easily erotic.

The other elements of the Modigliani story also remain too enticing to abandon altogether. There is still something compelling about the combination of his early brilliance and his doomed body. He had come down with pleurisy and typhoid by the age of 14, and at 16 he contracted the TB that would eventually kill him. His easy popularity makes him a captivating presence even now. He was the precocious child of Italy who became the darling of Paris. He moved, charming, feckless, from the bed of one woman to another, maddening them with his drinking and his temper, seducing them with his erudition (he knew long sections of Dante by heart), his talent and good looks. “How beautiful he was, my God, how beautiful,” lamented one of his models.

At the same time there were the grim terrors of poverty that beset many of the artists in Montmartre and Montparnasse in these years. And then there was his death in 1920 at the age of 35, which many saw as a kind of Faustian reckoning. “There was something like a curse on this very noble boy,” Cocteau wrote afterwards. So it was only fitting that it should follow the same fairytale pattern as his life. “Bury him like a Prince,” said the poet André Salmon, and they did: every artist in Paris followed his funeral procession to Père Lachaise. And then, to complete the story, his young, pregnant lover, Jeanne Hébuterne, followed him two days later, leaping from her window to join him in paradise.

So how do we go beyond the myth? Each biographer has had a new approach. The most recent, Meryle Secrest, has suggested, rather unconvincingly, that he wasn’t an alcoholic or a drug addict after all. Both the habit and the expression of it were manufactured in order to distract onlookers from the secret of his TB. Exhibitions have focused on elucidating the specifics of his Italian heritage or his social milieu. This new one at the Tate – his biggest retrospective in decades – makes much of his cosmopolitanism, reminding us that he was a Jewish Italian in Paris. It emphasises that he was a sculptor as well as a painter (remarkably, they have assembled nine of his sculptures from around the world) and examines his social and historical context. It sheds light on his relationship with cinema and contemporary fashion and attempts to give agency to his female models, rejecting a narrative of male artists making pictures for male dealers in which the women are merely the passive recipients of the male gaze.

This works well when it comes to Modigliani’s most significant love affairs. He didn’t shy away from falling in love with women with as much personality as he had, and there are three very interesting women to explore. Two of these, the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova and the South African-born British journalist Beatrice Hastings, were at least as professionally successful as he was. He met Akhmatova, who was married at the time, in 1910, and their affair lasted for more than a year. At this point he was a penniless sculptor, haunting the building sites of Paris by night in search of limestone. Of his isolation she recalled: “Everything in Modigliani only sparkled through a kind of darkness … He seemed to me encircled with a dense ring of loneliness.” They walked in the rain and recited Verlaine to each other. He drew her repeatedly and one of the few surviving drawings appears in the Tate exhibition. There is something otherworldly about her, reclining in bed: her hair forms a kind of halo and the sheet around her legs gives her the appearance of a mermaid.

The relationship with Hastings lasted longer, from 1914-16, and resulted in some intriguing paintings. Few letters from Modigliani survive, so Hastings’ columns for a London magazine form a crucial lens onto the artist in this period. These were the years that saw him making his reputation as a painter but also saw him succumbing more seriously to alcohol and drugs, and becoming more unpredictably irascible. After first encountering him, she described “a ravishing villain” dressed in corduroy. Soon she was complaining that he was “a pig and a pearl”: “the spoiled child of the quarter, enfant sometimes terrible but always forgiven”.

A feminist, dedicated to living unconventionally, Hastings smoked in public and matched her lover in his drinking. She also seems to have fought back. The myths about their quarrels still proliferate. There’s an anecdote in which he threw her through a closed window and she bit him in the balls. Certainly it was violent; undoubtedly it was creatively fruitful for him. Perhaps the most striking portrait of her is the one from 1915 where she’s figured as “Madam Pompadour”, an anglicised version of Louis XV’s smart and politically influential mistress. With her exuberant hats, Hastings appears as a woman of the world, her face and neck elongated in Modigliani’s now characteristic way. He had brushed with cubism, with the heavy lines of Toulouse-Lautrec and with the late portraits of Cézanne; he’d followed his Parisian contemporaries in learning what he could from African and Oceanic art. Now he was forging a style that was distinctly his, the lines outlining his figures clear and definite, the human shapes, whether of eyes or faces, echoing the almond-ovals of his sculptures.

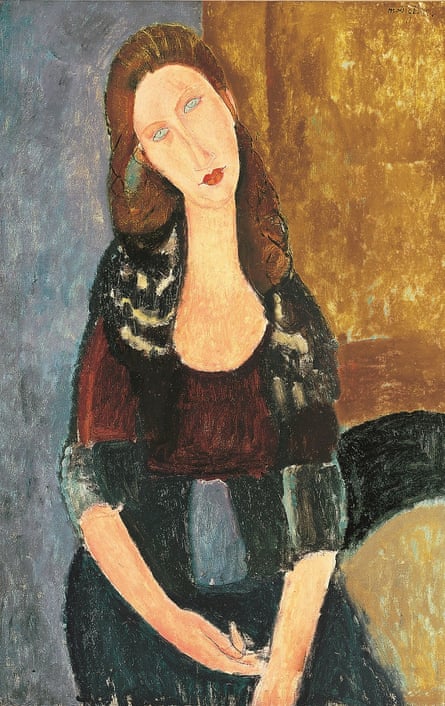

Then there is Jeanne Hébuterne, the most frequently painted of Modigliani’s lovers. They met in 1917 when he was 33 and she 19; she bore his child in 1918 and seems to have committed to him unconditionally even in his darkest times. Jeanne was undoubtedly the meekest of Modigliani’s serious lovers. Though she was a painter in her own right, it’s hard to argue that her career mattered much in years that were dominated by child bearing and curtailed by her willingly sacrificial death. If there’s a case to be made for her independence then it comes through the portraits, which, partly because there were so many of them, display a range of pose and attitude that goes beyond the merely submissive. Pregnant, she is majestic; painted only as a head, she is austere and determined; draped on a chair with her hair up, she has the languid poise of the modern woman.

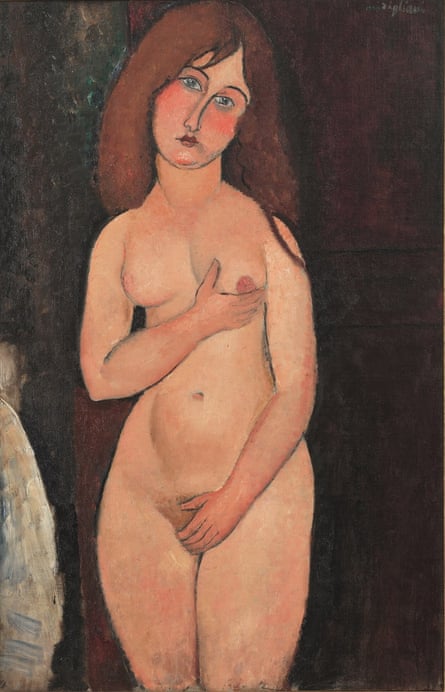

It’s possible, then, to create a narrative in which agency is given to Modigliani’s most significant mistresses. But what of his nude models – surely the paintings that many of the visitors will be there to see. The Tate has collected 17 of the nudes painted between 1916 and 1919, as well as an earlier one made in a darker expressionist style. Though some of the models of these paintings are given first names and are recognisable across several pictures, we don’t know anything about them. And it’s difficult to claim that they had the kind of equal status of Hastings or Akhmatova. Modigliani was typical of his day in refusing to paint nude the lovers he acknowledged in public, though it’s quite possible that he became the lover of his models.

The argument put forward by the exhibition’s curator Nancy Ireson is more complex. She suggests that these models can be identified as “new women” by their hair and make up. They were relatively well paid, earning five francs a day at a time when a female factory worker would earn two or three. And as a result they could participate in the new craze that saw ordinary French women as well as prostitutes buying the increasingly available cosmetics. Their red lips and dark eyes signify not that they were women of the night but that they were triumphantly of their times, influenced by female film stars. Certainly this is rendered convincing by their expressions in the paintings. Modigliani portrays them as erotic subjects in control of their own sexuality, fully able to answer the male gaze with desire of their own.

Visually, there is something unusually satisfying about looking at a Modigliani nude from his final years. It’s perhaps largely a question of form. The only one in Britain – the 1916 Female Nude on loan from the Courtauld – isn’t among the best. The torso is well shaped, the texture of the skin pleasingly wrought in thick strokes of rich orange and pink, but the head seems awkwardly stuck on the body, the angle of the chin unconvincing, the hair overworked. What it does display is the characteristic cropping of the arms and legs – in this case the painting ends just below the thighs – which allows his figures to move beyond the confines of the canvas, as though into the arms of the viewer or, in the case of the horizontal portraits, inviting the viewer in towards them.

A characteristic example is the wonderful Sleeping Nude With Open Arms (1917), where a woman lies, erotically splayed, her legs leading off beyond the edge of the picture. The gaze is drawn rapidly down so that the process of looking, if sustained, becomes a process of repeatedly caressing from head to thigh. Subtle variations in colour show the muscles in her stomach tensed with expectation; this is a woman recently touched and about to be touched again. Her arms, open behind her head in a gesture of deservedly self-satisfied display, seem about to move forward, allowing her to participate more actively in the scene.

Other nudes are more quietly languorous. The Tate show includes two willowy reclining figures from 1919, both apparently asleep, with the lines of the body taking us more slowly from left to right, rather than in that sharp descent. There’s even the occasional gesture of modesty, with a 1917 standing nude somewhat halfheartedly covering a breast and patch of pubic hair with her hands. It was the pubic hair that was the focus for shocked outrage when Modigliani first exhibited the portraits in 1917 (the police removed the nudes from the gallery, though the catalogue informs us that they didn’t close the entire exhibition, as is frequently claimed). According to Ireson, even this is a sign of the women’s modernity as well as the painter’s: this was the era when women began shaping their pubic hair with newly available instruments.

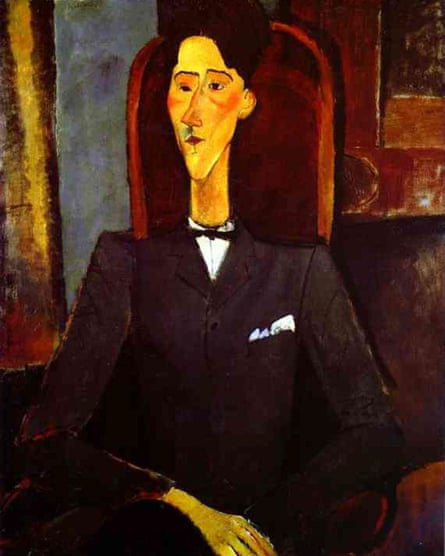

Though the nudes may be a highlight, the show aims to give a sense of his range. There are friends (Cocteau is among the most visually appealing), dealers and ordinary people. The Tate’s own The Little Peasant (1918) and the 1919 The Boy are moving portraits from his final years, where he seems to have returned once more to the influence of Cézanne, this time making the monumentality of his hero’s portraits more comfortably his own. The exhibition ends, as it must, with his haunting final self-portrait from 1919, his cheeks gaunt, his eyes half-shut with sadness and pain, but both the face and body as poised as ever. “Happiness is an angel with a grave face,” Modigliani had written, before painting himself in that role. And so the myth endures.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion