Call for national dementia database

- Published

- comments

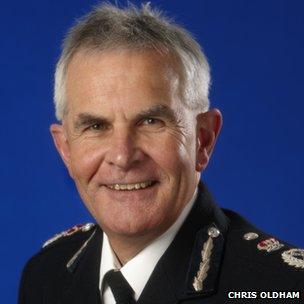

A police chief is calling for a national database holding the details of people suffering from dementia.

Sir Peter Fahy, Chief Constable of Greater Manchester, said it would help emergency services assist people who are either confused or agitated.

"It will enable the caring agencies to give a much better service when we receive a call and decide how to treat it," Sir Peter said.

The Alzheimer's Society said it could cause more problems than it solved.

It is estimated there are 800,000 people in the UK who are suffering from some form of dementia, and that figure is set to rise to more than one million over the next decade.

Many people with dementia live in the community rather than in care homes.

Greater Manchester, one of the largest police forces in England, estimates that the equivalent of 400 of its 7,200 officers each year are deflected from traditional policing roles to deal with people who have mental health issues.

Part of that mental health workload is related to people suffering from dementia.

"It's a growing issue and sometimes it is because people suffering from dementia go missing, sometimes it's because they have fallen at home and they are confused and we need to gain access on behalf of the ambulance service," Sir Peter told BBC Radio 5 live Investigates.

"We have some people with dementia who are ringing us 30 times a day and clearly we have to take every one of those calls seriously," he added.

'Under the radar'

He said the police service needed to look at procedures which would ensure people with dementia get a better service.

"One thing I would like to see is a national database where carers and the families of elderly vulnerable people can put their contact details so if the police or ambulance get a call to that particular address, they can phone that relative and immediately get some background information," Sir Peter said.

"While some might see that as a threat to civil liberties and the state having too much information - in reality it will enable the caring agencies to give a much better service," he added.

But the Alzheimer's Society, which campaigns for improved services for people with dementia, is wary about such a scheme.

"Too many people with dementia currently go under the radar, and lose out on access to the health and social care support they need. Agencies like the police need to be able to identify people with dementia but giving them access to a national database may pose problems," George McNamara, the head of policy at the society said.

"If the police and social services were to simply share existing information more effectively, this could go a significant way towards aiding the police and enabling people with dementia to live independently in their own homes," he added.

Research by the BBC has shown that some police forces have seen an increase in incidents involving people with dementia. Around a quarter of forces across the UK - 14 - were able to provide figures, based on a trawl through their incident logs.

All the forces that responded indicated that these incidents had risen over the last two years.

Sussex Police, for example - which covers the popular retirement towns on the English south coast - saw an increase from 682 in 2010 to 1,815 in 2012.

Complex issue

People with some rarer forms of dementia can exhibit anti-social behaviour and as a result of their symptoms, may be more likely to come into contact with the police.

Angela Potter's husband was diagnosed with fronto-temporal dementia when he was 50. This form of dementia affects people's ability to reason and communicate.

"His character changed and just became less inhibited. He started to shoplift. He saw things that he wanted and he just took them, he didn't understand that you have to pay. He was banned from many shops," she said.

Fortunately her local community police officer in north London was sympathetic.

"He met my husband and understood the situation. He was willing to listen and try and understand and I called him any time I needed to, he was always very helpful," she said.

In Greater Manchester, Sir Peter said dealing with people with dementia and mental health issues can deflect officers from their more traditional roles.

"Sometimes it feels like crime is an ancillary activity for us - and to some extent crime is relatively straightforward. We know what to do with a burglary or a burglar.

"But often you are dealing with a complex issue involving a vulnerable person and you are struggling to get help from a medical person, and that can be a very difficult issue to solve," he added.

"An officer can be tied up for five, six or seven hours at a hospital waiting for a proper assessment to be made or waiting for them to be found a bed - and that clearly is a huge use of police time, it affects police morale and absolutely affects our ability to do our primary job of reducing crime."

In a statement the Department of Health said: "There are no plans to introduce a national database of dementia patients. Any decision to do so would have to be backed up by robust evidence demonstrating that it helps vulnerable people with the condition remain more independent. The choice of being included on such a database must be made by the individual and their family.

"We want to ensure that people with dementia can lead as independent lives as possible. This is why schemes such as Dementia Friends, which help to raise public awareness and understanding of the condition, are so important."

- Published9 September 2013

- Published27 June 2013

- Published18 June 2014