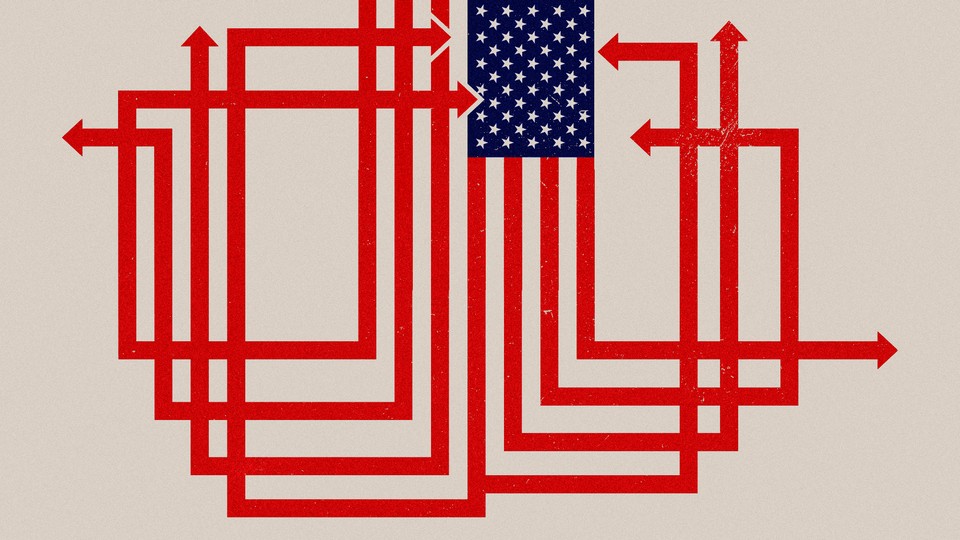

How Russian Trolls Imitate American Political Dysfunction

When it comes to sowing discord, U.S. politicians and pundits have had plenty of practice.

Suppose you were a vast global conspiracy plotting to foster discord among Americans. How would you approach your task?

You might try to spread some salacious but dubious accusations—say, that a politician is a “devotee of Bigfoot erotica.” But that particular charge would feel kind of stale, since a Democratic congressional candidate already lobbed it at her rival this summer.

Maybe you could think bigger, and make a video that tries to red-bait a candidate by linking him loosely to George Soros and, from there, even more loosely to “antifa.” But that would be superfluous because the National Republican Congressional Committee already funded such an ad.

You could always signal-boost some evidence-free conspiracy theory—perhaps the idea that “unknown Middle Easterners” have infiltrated the caravan of immigrants marching toward the Mexican border. But you’d be wasting your patrons’ money: That theory already got an enormous signal boost when the president of the United States endorsed it on Monday.

It’s enough to make you feel a little pity for Elena Alekseevna Khusyaynova, a Russian woman who stands accused of plotting against the United States. Last week, the feds charged her with what CNN is calling a “conspiracy to hurt American democracy,” but her alleged activities look a lot like … American democracy. What’s a subversive got to do to actually have an impact around here?

The criminal complaint against Khusyaynova claims that she and her co-conspirators aimed “to sow division and discord in the U.S. political system” by “creating social and political polarization.” To that end, it says, they adopted false online identities and used them to “inflame passions on a wide variety of topics, including immigration, gun control and the Second Amendment, the Confederate flag, race relations, LGBT issues, the Women’s March, and the NFL national anthem debate.”

In other words, they mimicked a bunch of all-American politicians and pundits, many of whom spend the home stretch of every election trying to polarize us and inflame our passions, often by invoking those very issues. And then the Russians added a little more shouting to the din.

Not that their disguises were flawless. The FBI agent’s affidavit against Khusyaynova claims that her conspiracy started an anti-immigration Facebook group called “Stop A.I.” This, the agent informs us, was an abbreviation for “Stop All Invaders.” The page no longer exists, so I don’t know how many people joined it looking to put the brakes on artificial intelligence.

It would be nice if we could stick to debating the Khusyaynova charges on their own terms. Reporters could probe how true the accusations are; lawyers could argue about whether the activities rise to the level of illegal fraud; civil libertarians could question whether the government should police what ultimately amount to acts of speech. We could have a normal news cycle about a single set of accusations.

But in 2018, this story inevitably flows into a much larger narrative. Over the past two years, there’s been a steady drumbeat of reports about Russians spreading fake news, creating fake social-media accounts, and forming fake groups that try to organize real demonstrations on U.S. soil. The reporters frequently add the appropriate caveats and cautions, but even then, many of their stories are framed in ways that scapegoat Moscow for America’s domestic political divides. (When The New York Times runs a headline like “How Russia Harvested American Rage to Reshape U.S. Politics,” note how it puts the Russians, not the raging Americans, in the driver’s seat.) This country has a long history of blaming its problems on alien infections, and it’s easy to insert these Facebook pod people into that old legend.

So it surely matters that these stories tend to feature far more examples of Russians imitating Americans than influencing Americans. Even what at first glance might seem like a big success—the time Russian poseurs drew thousands of protesters to an anti–Donald Trump march in New York City—looks less impressive when you realize how they did it: by scheduling it at a time and place that was already seeing constant marches against Trump. Senator Angus King of Maine once said that Moscow wants to “take a crack in our society and turn it into a chasm.” These folks found a chasm that was already there, and they used it as camouflage.

More often, they take a crack and don’t turn it into anything larger at all. We learned a few months ago that a rally for Texas secession organized covertly by Russians could attract a “few dozen” supporters. If that sounds impressive, remember that the same cause could draw a “few hundred” to an event in the 1990s, when Moscow and Washington’s post–Cold War relationship had not yet ruptured.

Any country that contains competing interests is going to be divided in many ways, and elections are precisely the time when you should expect passions to be inflamed around those divisions. That is not in itself a bad thing. The problem with that Soros-antifa ad isn’t that it talks about divisive issues; it’s that it’s a guilt-by-loose-chain-of-association smear. The best defense against messages like it is to learn how to recognize a bad argument or a poorly sourced story, and to put the word out when it’s been debunked. That’s an enormous task, but it’s no more enormous than trying to block people from spreading such smears in the first place. And it does have the advantage of working just as well whether the smears come from Russians or Americans or anyone else.

None of this means we should simply dismiss the Khusyaynova story and others like it. The activities outlined in this affidavit may not be the hidden explanation for the battle lines in American society, but they’re a useful window into the world of online fakery.

That world contains much, much more than Russia. Foreign powers ranging from China to Saudi Arabia have troll armies, and the U.S. itself has invested military money in an “online persona-management service” that “will allow 10 personas per user, replete with background, history, supporting details, and cyber presences that are technically, culturally and geographically consistent.” For that matter, it’s not just governments that do this sort of thing. It’s domestic political campaigns. And apolitical viral marketers. And alternate-reality games. And catfishers. And pranksters. And every business that’s ever produced a fake Yelp review. Pull back from that vast-foreign-conspiracy frame and you’ll see a bigger and messier tangle of deceptions and identity games online.

The Russia focus can obscure just how large and long-standing this global masquerade ball is. One recent New York Times piece, for example, includes a pro forma statement that “politics has always involved shadings of the truth via whisper campaigns, direct-mail operations and negative ads bordering on untrue.” But it also declares that things are “different this time” because “domestic sites are emulating the Russian strategy of 2016 by aggressively creating networks of Facebook pages and accounts—many of them fake—that make it appear as if the ideas they are promoting enjoy widespread popularity.”

A claim like that depends on an astounding amount of amnesia. The adaptation of such a strategy to Facebook may be relatively new, but the use of internet tools (and pre-internet tools) to create an illusion of widespread popularity is not. A decade ago, online disinformation campaigns involved comment threads and email forwards; now it’s tweets and Facebook memes. The technological landscape may be different, but anyone who’s seen a horde of suspiciously similar blog comments promoting a candidate or cause can tell you that the process has been around for a while. When it comes to sowing our own discord, Americans have had plenty of practice.