London is without question the most popular city for investors,” says Gavin Sung of the international property agents Savills. “There is a trust factor. It has a strong government, a great legal system, the currency is relatively safe. It has a really nice lifestyle, there is the West End, diversity of food, it’s multicultural.” We are in his office in a block in the centre of Singapore and he is explaining why people from that city-state are keen to buy residential property in London.

He’s right – London has all these qualities. It has parks, museums and nice houses. Its arts of hedonism are reaching unprecedented levels: its restaurants get better or at least more ambitious and its bars offer cocktails previously unknown to man (coconut seviche, for example, where, as its makers put it, “coconut gin is swizzled through crushed ice with yuzu, passion fruit and a dark chocolate liqueur, and served long with an accompanying ‘shot’ of tuna seviche with a tamarind ponzu”). In some ways, the city has never been better. It has a buzz. Its population keeps growing and investment keeps pouring in, both signs of its desirability. As its mayor likes to boast: “London is to the billionaire as the jungles of Sumatra are to the orangutans. It is their natural habitat.”

At the same time, to use a commonly heard phrase, the city is eating itself. Most obviously, its provision of housing is failing to keep up with its popularity, with effects on price that breed bizarre reactions at the top end of the market and misery at the bottom. Thousands are being forced to leave London because their local authorities can’t find them homes and people on middle incomes can’t acquire a place where anyone would want to raise a family.

There are also effects beyond housing, although often driven by residential property prices. The spaces for work that are an essential part of the city’s economy are being squeezed, its high streets diminished, its pubs and other everyday places closing. It is suffering a form of entropy whereby the distinctive or special is converted into property values. Its essential qualities, which are that it was not polarised on the basis of income, and that its best places were common property, are being eroded. It is becoming the case that delights and beauties are available only at a high price.

This would matter less if the city were making new places with the qualities of those now packaged up and commodified – if the supply of good stuff were expanding – but it is not. Although the cranes swing, much of the new living zones now being created range from the ho-hum to the outright catastrophic. The skyline is being plundered for profit, but without creating towers to be proud of or making new neighbourhoods with any positive qualities whatsoever. If London is an enormous party, millions of people are on the wrong side of its velvet rope.

In the rest of Britain, a common view of London is that it is a parasitic monster or, as Alex Salmond put it, quoting Tony Travers of the London School of Economics: “The dark star of the economy, inexorably sucking in resources, people and energy. Nobody quite knows how to control it.” Both the SNP and Ukip can be seen as anti-London parties, as expressions of a feeling that national decisions are made in the capital, by the capital, for the capital. Those Scots who want independence are less concerned about being part of the same country as Middlesbrough or Ipswich than they are about London. But these views overlook the extent to which the city is feeding on its own. And, dear readers outside London, who may be reasonably wondering what all this has to do with you, consider that the city is one-seventh of the country as a whole and that what happens there may well, in some form, also come to a place near you.

Take, for example, a row of railway arches in Atlantic Road and Brixton Station Road, Brixton, south-west London, where shops serve the various needs of the area’s communities: fish, Afro-Caribbean hair products, budget carpets, a pawnbroker, a Mediterranean delicatessen that still has the awning installed in the 1970s, when it was Greek-run, but which serves just as well the current management, which is of Portuguese descent. It is run by José Cardoso, whose father took over the shop in 1990. “The fishmongers are in their third generation,” he says. “Some of the businesses have been here for 20, 30 or 40 years.”

His shop, he says, serves everyone “from the white middle class buying Parma ham and olives” to “immigrants getting day-to-day stuff and green coffee”. Yet, like the others in the arches, he has been given notice to quit by Network Rail so that it can renovate them, a process that it says will take a year or more, with the offer of £7,000 compensation and no right to return. The arches don’t obviously need renovation, apart from some repairs to the external brickwork. Cardoso’s shop works just fine as it is. There is every reason to think that the plan is to turf out the existing tenants so that higher-paying businesses can move in: chains and more pretentious and exclusive shops.

Cardoso doesn’t know where he will go. He is thinking of becoming a taxi driver. If he manages to find another place, the rent will be much higher. “We would have to go upmarket,” he says. “It would exclude a whole section of our customers and force them to buy in the chain supermarkets.” His and his staff’s livelihood, a piece of the area’s social fabric and a shop that sells extremely good products without the flummery and expense that accompanies many high-end delis will, together with the other vital businesses in the arches, disappear.

Meanwhile, in Hackney Wick, east London, in the zone uplifted by the Olympic Games of blessed memory, a number of successful industries are facing the prospect of removal to places unknown or possibly nonexistent. The old London brand of Truman’s beer, which, as its sign announces, was founded in 1666, closed in 1989 and re-established in 2010, would like to expand into adjoining buildings but, instead, will have to leave altogether, to make way for a residential development. Dalston Cola, which makes fizzy drinks with low-sugar content and relatively subtle flavour, also clings precariously to its modest space. Again, Armageddon will come in the form of blocks of expensive flats.

Industry is the forgotten part of London’s economy, denigrated and overlooked since the years of Margaret Thatcher, assumed to belong to a lost 1970s world of flat caps and powerful trade unions, its premises labelled “brownfield” and therefore considered ripe for redevelopment, the noun “industries” routinely prefixed with “failing”. Yet it still accounts for 11% of the capital’s economy. It provides essential services. “There is a vast diversity of smaller businesses,” says Mark Brearley of the Cass Cities unit at London Metropolitan University, “that is unstoppably, entrepreneurially driven. It is so fascinating to watch the refreshing of industry in London: things that people had written off are reviving and growing.”

It creates employment and of a certain social value. “The jobs that I provide,” says the founder of Dalston Cola, Duncan O’Brien, “don’t require a university education, but they are skilled and provide career progression. We are not call centres. They are jobs with futures. They establish long-term relationships with local communities. But you can’t do that if you are always being pinged around the city, from one place to the next.”

Industry in London is thriving as best it can. It includes niche makers of food and drink, tech industries, skilled clothing manufacture, glass makers, steel fabrication and vehicle repair. Yet the space it is allowed is contracting. In Tottenham, and along the valley of the river Lea, the places where people can make things are giving way to flats and more flats. As Brearley puts it: “There is a shortage of capacity for economic and cultural life; the city is much less able to nurture entrepreneurialism.”

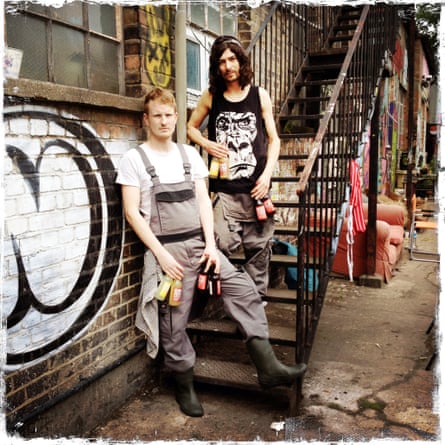

It is a similar story with artists’ studios. “There is a pretty hellish pressure,” says Anna Harding of Space studios, which has been providing workspace to artists since the 1970s. “I don’t know how we can continue.” Because Space owns rather than rents some of its properties, it can cushion some of the shock that comes from rent increases of 100% or more and asks its tenants for no more than an extra 20%. But it is still “a stress for tenants. How can they find the extra?”

Duncan Smith, artistic director of another studio provider, Acava, says that the “situation is becoming critical. In the 12 months starting from six months ago we will have lost 200 studios. Traditionally, we rented premises for five-, 10- or 15-year terms, but suddenly they are all disappearing at once.” Eighty of these are in an Acava-managed block in Cremer Street, east London, where the artists were asked by the building’s owner to sign a letter in which they agreed not to oppose its redevelopment as flats, in return for which they will be evicted later rather than sooner. Mostly, they agreed, as “they have no legal basis to protest” and because “they have very few places to go. As “art is a profession and people have professional obligations”, they would rather stay put for as long as possible.

For Harding, artists are part of “the whole ecosystem that makes the city functional”. Smith points out that they come with networks of associated skills – “web designers, advertising people, film-makers and all the rest”. London has been selling itself on its creative reputation for at least 20 years. “There’s great talent,” says Harding, and “it would be really foolish for the whole city economy to kick it out”. Might it not be a good thing if artists took their regenerative stardust out of the capital to other parts of the country that would really benefit? Acava, indeed, is opening studios in Essex and Stoke-on-Trent. “But”, says Harding, “London works because there’s a market there. Collectors fly into London and want to visit studios. Galleries need to see them.” There are the technicians who support the art, many of them also artists, “people earning ten grand a year. The museums need them. The idea that you can devolve it all is nuts.”

Then there are the pubs, those quintessences of British culture that also have the ability to give space and identity to a city’s multiple communities. These might be places such as Canterbury Arms in Brixton, described by one who knew it as “a social hub for so many years”, now “flattened and turned into flats”. They might be LGBTQ pubs such as the Black Cap in Camden or the Joiners Arms in Shoreditch, both also closed, though a version of the latter has now reopened in Sitges, Spain. There is uncertainty about the future of south London’s Royal Vauxhall Tavern, the gay landmark into which legend has it Princess Diana was once smuggled, dressed as a man, with the help of Freddie Mercury and Kenny Everett.

All of which is laid on top of the losses already suffered in public services because of cuts, such as the closure of six libraries in the borough of Brent, and the rebuilding of a seventh, in Willesden Green, beneath a block of flats and without a much-loved bookshop that had previously been there. It has fallen to local community groups to try to reopen at least some of these, but for now they all remain shut. In Camden there are plans, still under discussion, to close day centres for people with learning difficulties, dementia and other mental health problems, and replace them with a single centre. Objectors say that people with very different needs will be put together in a “warehouse”, and will lose the intimacy of their current centres.

Most of the time these shrinkages are for the same reason, which is that there is no more profitable use for land than residential development. If a landowner can convert a factory, an artists’ studio building, a pub or library into flats, colossal windfalls can be made. Because London is seen to suffer from a housing shortage, planning policy tends to look favourably on such conversions. Harding says that there has long been pressure to convert the sort of industrial spaces that artists occupy into loft apartments, but “now it is in hyperinflation mode. Owners can knock them down and put up 42-storey towers and make a fortune”. The consequences, says Brearley, are what are in effect “steroidal suburbs” – monocultural developments that, like the worst of postwar housing estates, only serve one function.

According to Vince McCartney of Holborn Studios, “there will be a corridor of steel and glass from King’s Cross to Limehouse” – a distance of about five miles along the Regent’s Canal – as waterside spaces are made into flats. This could include his studios, a centre of photography that Helmut Newton described as the “Abbey Road” of the art. Its buildings, arranged around a sociable courtyard and a slice of towpath, also nourish a community of businesses that sustain between 250 and 300 jobs, all of which could go if the site’s new owner, Galliard Homes, has its way. “The whole thing is greed-driven,” says MacCartney. “It’s time to say enough. How much development can it stand?”

When properties don’t change as a direct result of conversion to housing, as with the Brixton railway arches, they do so through an indirect consequence: the raising of house prices in an area can mean that there is more money to made from eateries and speciality retail, which pushes out the places that serve the communities already there.

At the same time, the housing market is doing violence to itself by demolishing ideas of what a home might be. It has generated such headline-christened phenomena as iceberg houses, lights-out London, social cleansing and beds in sheds. There are also what Peter Rees, who spent 29 years as the City of London Corporation’s chief planning officer, calls “safety-deposit boxes in the sky” – towers of flats whose main purpose is not to make homes or communities, but units of investment.

If you walk through Knightsbridge in the evening, at a time when people in well-adjusted cities might be having dinner with their families and friends, or at least watching TV with their kids, you will see a wall of black, punctuated by the odd square of illumination. This is One Hyde Park, the housing block of notorious expense that was designed by the practice of the left-leaning architect Richard Rogers and pushed through by the socialist mayor Ken Livingstone against objections to its impact on the miraculous slice of nature that is Hyde Park. It was essential, in Livingstone’s view, to keep welcoming the global wealth that buys such places, the billionaires who would later delight his successor, Johnson. Whoever bought these flats (oligarchs and sheikhs is the usual assumption), don’t find reason to be there very much, hence the blackness.

If you tour other luxury areas, you will find two contradictory tendencies. On the one hand, they are enervated, depleted, losing energy, as shops and restaurants find that their businesses can’t be sustained by the occasional populations of these neighbourhoods. The other is expressed in flurries of construction activity – dust, noise, machines, workers, trucks carting off piles of mud – as if mining companies were extracting something precious from beneath the well-tended stucco of the Victorian terraces. Which is exactly what they are doing, the precious stuff being thousands of cubic metres of additional prime property. These are iceberg houses, with basements larger than the historic bauble perched on top, to be filled with private cinemas, bowling alleys, swimming pools, gyms, spas, whatever takes the owners’ fancy. It is expensive to make such basements, but the increase in value more than pays for them.

More and more space is being formed, in other words, and it is getting emptier and emptier. Meanwhile, if you fly in a helicopter over suburban boroughs such as Hounslow or Newham, as council enforcers sometimes do, you will see ramshackle structures in back gardens, some of which will be housing uncounted numbers of migrants. Whereas iceberg houses are permitted by loopholes in the planning system (which some local authorities are now trying to close), these are unauthorised and try to evade detection. A Brazilian architect once asked me why there were no favelas in London. They are coming now – sheds in back gardens, small flats and houses appallingly overcrowded.

The contrast between legal iceberg houses and illegal beds in sheds is striking because of the spectacular difference in their respective ratios of number of inhabitants to available volume. What they have in common, along with lights-out London and safety-deposit boxes in the sky, is the abandonment of any kind of domestic or neighbourly ideal. The concept of home as a place of delight and nurture, or of a neighbourhood as enriching and social, is obliterated by the logic of exploitation. The “nice lifestyle” of which Gavin Sung speaks and on the basis of which London is sold abroad gets forgotten.

The notion that a home might shelter your dreams and identity, and be something you could take pride in, is also unavailable to the millions who cannot afford to buy or to rent on reasonable terms. For some, the possibility that you might stay in your locality, close to your networks of family and friends, your children’s schools or your place of work, is being taken away. According to the Independent, more than 50,000 families have been moved out of their boroughs in the past three years. Some go to other parts of London, usually to outer and more disadvantaged places, which adds to the pressure they are already feeling. Some, says the report, are shipped to places such as “Manchester, Bradford, Hastings, Pembrokeshire, Dover and Plymouth”.

More of these people could stay put if it were not for the destructive examples of “estate renewal”. At its best, this is the process by which run-down old council estates are repaired and upgraded. At worst, it sees the demolition of thousands of homes, the eviction of people who, in some cases, might have been there for decades and the building of new homes mostly for sale at market rates, with a much smaller number at rents that the former residents could afford. According to the website mappinglondonshousingstruggles, at least 70 estates are being made over in this way, affecting 160,000 people.

An early version of this was the Heygate estate in Elephant and Castle, south London, where 1,194 council flats were demolished to make way for a new development of 2,500 homes, of which a mere 79 will be available as “social rented” units, which is the modern term for what a council home once was. A further 506 will be available at less generous levels of affordability. To achieve this reduction required the expenditure of some millions by the local authority, Southwark, the handing over of 25 acres of valuable land to the private sector, the uprooting of existing communities and 15 years of argument and broken promises.

It might not therefore be considered a triumph for the public good, yet it turns out to have been a prototype for similar operations across the capital – on the West Hendon estate in the borough of Barnet, for example, and on the Aylesbury, the vast estate near the Heygate, south London. The creation of new homes by obliterating old council estates had also been backed by both the Labour peer Lord Adonis and the Conservative housing minister, Brandon Lewis, who announced to a recent gathering of property professionals that the government had set aside £150m to “kickstart” the regeneration of “those inner-city estates that are dominated by the high-rise blocks of the 1960s and 70s”.

“By far the largest source of publicly owned land suitable for new housing,” says Adonis, “is existing council housing estates.” As many of these were built to low densities, he argues they can be rebuilt with larger numbers of homes. He says that “redevelopment of estates is sometimes assumed to mean that existing tenants and residents will be displaced by wealthier incomers. This need not, nor should it be, the case.” Sometimes, indeed, such equitable redevelopment can and has been achieved. The problem is that on the Heygate and elsewhere it has not. The Adonis/Lewis view also tends to set at zero the value of existing networks of community and friendship, people’s attachment to their homes or the architectural qualities that, despite their popular reputation, such estates often have. They are considered in effect as brownfield sites, even though they often have a lot of green. Sometimes, their open spaces and gardens are the first parts to go, in the name of densification and efficient land use.

The borough of Lambeth, an enthusiastic builder of social housing in the 1960s and 70s, is now an equally enthusiastic ripper-up of its own legacy. In particular, there are the estates created under the leadership of the borough’s chief architect, Ted Hollamby – humane, rich, complex places, which learned from mistakes of the over-rigid and systematised projects that gave postwar council housing a bad name. There is, I’m told, a Ted Hollamby Society in Germany, so esteemed is his work there, but on his home turf, as the campaign group Architects for Social Housing has highlighted, almost everything he created is under threat.

In Crystal Palace, for example, on the edge of Lambeth’s territory, the council has plans, so far undisclosed, to “regenerate” the Central Hill estate, 470 homes draped beautifully around a hilly terrain, with an astonishing variety of courts and gardens, mature trees interspersed with buildings, terraces turned to face magnificent views and extensive car-free areas where children play happily and neighbours meet. The homes are well planned, using limited space well and catching light from different directions. Recent form suggests that “regeneration” will mean demolition. Council tenants will have the right to replacement dwellings, but this does not include such things as retaining the amount of garden space they already have or compensating for the associations, friendships and personal histories that will be ruptured.

Something you hear again and again from those displaced from jobs, home or social life by residential development is the acknowledgment that “of course London needs new homes”. They usually add “but not the homes that are actually being built”. Most of the time, these are designed as units of speculation, for both British and overseas investors, often sold off-plan in property fairs in Asia. The requirement to provide affordable housing is usually negotiated down by developers to as low a figure as they can get away with.

Asian buyers are entitled to invest in British property and nobody knows how many properties acquired by them or anyone else will remain empty. “I am sat here [Singapore] and I don’t believe it,” says Sung of the “concept of Asians doing nothing with their property”. “Chinese culture and history is to get a return for your money.” Those that will be rented out will in some way answer an aspect of demand. But, empty or not, such units will not be best suited to meeting the needs of most Londoners, nor creating sustainable new communities.

In Brixton, I meet Alex Holland, a former Labour councillor who with others successfully campaigned to save Brixton Market from redevelopment as flats. The market, in two halves on either side of Atlantic Road, is a place where adjectives such as “vibrant” and “diverse” still have meaning; also “useful”, as in serving people’s everyday needs. As he concedes, however, neither he nor anyone else can halt the process by which the Latin and Caribbean fruit and vegetable shops, the Sierra Leone groceries, the sellers of fish, wholesale meat, hardware and wigs gradually make way to outlets such as Champagne + Fromage, the “shop and bistro” that “brings rustic fare and fizz to London, served the French way”. A more than usually blatant agent of de-Brixtonisation, its opening attracted protests.

“But,” says Holland, “don’t hate the players, hate the game.” Duncan Smith says something similar of the property owners who want to make artists’ studios into blocks of flats: “We cannot protest at what a landlord is entitled to do.” The point is that these people are doing what most people in their position would do, because the system encourages them. The same goes for Singaporean investors to whom Gavin Sung sells.

In this case, the game is one constructed by property values, local government finance and the planning system, as modified by recent government policies. In particular, there was the relaxation by the then communities secretary, Eric Pickles, in the days of the coalition, of the restrictions that previously prevented the conversion of industrial and commercial space into residential. In some places, local authorities have won the right to retain these controls, but where they have not it is a no-brainer for landowners to make many millions by turning their workplaces into units of residential investment.

Even when the planning system protects, for example, the use of a location as a shop or restaurant, it has few ways of defining what sort of place that might be. It cannot tell the difference between a shop such as José Cardoso’s and an Asda, or between a gay pub with decades of social history and glass-walled retail unit at the bottom of a new tower of flats. Places can now be designated “assets of community value”, which gives local groups the opportunity to come up with bids for such sites, but it does not seem to be making much real difference. Efforts to insist on retaining some workspace in Hackney Wick are unlikely to provide space of the type and price that local businesses need.

At the same time, local authorities have had their budgets assaulted, which puts pressure on them to come up with money in any way they can, which helps explain why boroughs such as Lambeth want to make as much as they can out of the property they own in places such as Central Hill. It is also the reason why libraries and day-care centres have closed or are threatened.

Which brings us to an outrageous inequality in the government’s attitude to austerity. The deregulation of the restrictions on conversion of sites from other uses to residential is in effect a colossal gift to those lucky enough to own them; a jackpot, a shower of golden coins from a vast, state-owned slot machine. At the same time, local authorities are bullied and squeezed into surrendering their assets, at whatever cost to their residents and tenants, just to keep financially afloat.

Beyond this inconsistent generosity is the failure by national government and London’s mayor to face up to the scale of the issues involved. London’s population is expected to reach 10 million by 2031, which would be 150% of its mid-1980s level, within the constraints on expanding sideways set by the green belt. This is a vast challenge that is about more than counting bedrooms. “Of course there’s a housing crisis,” says Harding, “but there’s also an employment space crisis. It includes highly professional artists and creative businesses, the self-employed and sole traders that are the future of employment.”

“Just when you thought you had one giant unsolvable problem, in housing”, says Brearley, “you find you also have number two.”

Serious consideration of both giant problems should include such options, ideologically difficult for the current administration, as publicly led building on publicly owned land, and (with good planning and a high degree of caution) building on those parts of the green belt that are not actually significant natural or agricultural assets. Instead, the only approaches that this government knows are to deregulate and incentivise the private sector, in the belief that, ultimately, it will meet the city’s housing needs unaided. Which it has not, for many decades, done, if ever. The result is that the weak spots, in market terms, are cannibalised. What goes is the soft but essential tissue that makes the city worth inhabiting and that, ultimately, makes it desirable to those outside investors.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion