An Earth-sized world that swings around a star in the constellation of Aquarius has become a priority in the search for extraterrestrial life after scientists found that an atmosphere could have enveloped the planet for billions of years.

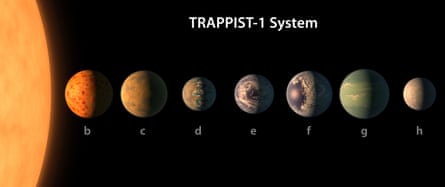

The planet is one of seven circling a small and feeble star called Trappist-1 which astronomers reported in a wave of excitement in February this year. The rocky world lies in the habitable zone around its parent star, where temperatures should allow for free-running water, but that would count for little if the planet has no atmosphere.

“Since the discovery of the seven planets there has been a great deal of interest in using telescopes such as the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope to determine whether these planets have atmospheres, and if so, what their composition is like,” said Manasvi Lingam at Harvard University. “It is fair to say that the presence of an atmosphere is perceived as one of the requirements for the habitability of a planet.”

If Earth serves as a good example, the evolution of complex and ultimately intelligent life calls for an atmosphere that not only contains the right blend of gases, but which persists for hundreds of millions, or preferably billions, of years.

With Nasa’s James Webb Space Telescope not due to launch until late 2018, the scientists turned to computer models to find out whether the Trappist-1 planets could have long-lived atmospheres. From details of the Trappist-1 system, which lies 39 light years distant, they worked out the intensity of the stellar wind – the rush of high energy particles streaming out of the star – and the effect it would have on the seven orbiting planets.

Atmospheres that exist around planets soon after they form can gradually be stripped away if they are battered by a strong stellar wind from their parent star. The model showed that the stellar wind from Trappist-1 was much faster and far more dense than the solar wind that reaches Earth. On Trappist-1b, the first planet from the star, the stellar wind was 1,000 to 10,000 times stronger than the solar wind that strikes Earth.

The intensity of the solar wind destroyed the atmospheres of the inner Trappist-1 planets within millions of years. But planets further out fared better, their atmospheres surviving for billions of years, the models found. According to the scientists, while the seventh planet around the star is considered too cold for liquid water to exist on the surface, the sixth planet, Trappist-1g, appears to be the most likely home for life in the Trappist-1 system.

In a report submitted to a leading journal, the scientists write: “The outer planets of the Trappist-1 system, which are expected to retain their atmospheres for longer periods, may therefore support more complex biospheres eventually.”

Amaury Triaud, an exoplanet researcher at Cambridge University who helped discover the Trappist-1 planets said: “The work is quite optimistic that the planets could retain an atmosphere, which is nice to hear. It prepares us for what we might or might not see. Maybe we’ll find atmospheres that are denser and denser for the outer planets.”

“Having too much of an atmosphere containing a lot of hydrogen would be detrimental for life, but if you strip everything down to the surface, it’s also no longer habitable. The moon is the same distance from the sun as the Earth and it has absolutely no signs of life,” he added.

Astronomers have now detected about 3,600 planets beyond the solar system. The Trappist-1 planets orbit incredibly close to their parent, an ultracool dwarf star the size of Jupiter that shines 2,000 times less brightly than the sun. Mercury, the innermost planet in our solar system, is six times farther from the sun than the outermost seventh planet is from Trappist-1.

All seven of the planets have Earth-like dimensions, ranging from 25% smaller to 10% larger than our home planet. Most, if not all, will be “tidally locked”, meaning they show only one face to their star. Such worlds would be defined by stark divisions, with one half in constant daylight, and the other in permanent darkness.

“We don’t really know how life started,” Triaud said. “Some people say life was born at the bottom of the ocean. If that is the case and there is a lot of water on the Trappist-1 planets, then it’s good news: it doesn’t matter which side it is on, because at the bottom of the ocean you have no light at all.

“But if life is born on the surface then the UV irradiation the planets receive is important. It drives chemical reactions to begin with, but it can become an issue for DNA mutations, and whether they were on the day or the night side would matter. There really are a lot of elements,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion