A new monograph dedicated to the late photographer’s avant-garde oeuvre cements her status as much more than Edward Weston’s muse, Diego Rivera’s lover and Frida Kahlo’s best friend

In 1930, the Italian photographer Tina Modotti found herself behind bars. Authorities believed she was the culprit behind the attempted assassination of Pascual Ortiz Rubio – the soon-to-be-elected president of Mexico. After 13 days in prison, the artist and prominent member of the Mexican Communist Party was eventually released and deported – a decisive moment that brought about the end of her photographic career.

A new monograph, eponymously titled Tina Modotti, re-situates her in the history of photography. It shines a light on rarely-seen works produced in 1920s Mexico, before she had become an enemy of the state. Published by La Fabrica, the photo book assembles over 400 black-and-white works created during a formative and experimental chapter in her life. Like other Europeans who journeyed to Mexico – when it represented a fertile breeding ground for radical art and politics – Modotti rubbed shoulders with avant-garde creatives, from her lover (and celebrated photographer) Edward Weston, to the artists Jean Charlot, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Such circles – sometimes known as Rivera’s ‘La Familia’ – met regularly, and their ideas shaped her artistic and political vision.

Born in 1896 in Udine Italy, Modotti came from humble origins; her father was a mechanic and her mother a seamstress. She followed her father to New York in 1913 and later to the West Coast, where she had a brief career as an actress in San Francisco. By the age of 26, she had become a minor celebrity in the Italian community of San Francisco, starring in films such as The Mission Play about the history of Franciscan missions in California. She would go on to work in Hollywood, where she became acquainted with Weston in 1921. An intense relationship quickly ensued – Modotti becoming his lover, muse and apprentice. In 1923 they moved to Mexico together where, encouraged by Weston, she decided to take up the camera herself.

Although inspired by Weston, she developed her own vision, one responding to the post-revolutionary Mexican Stridentist movement, explaining why industrial themes and motifs often appear in her work: telegraph cables, bridges, stadiums and tanks. The streets became a rich source of inspiration: “Mexico reminds me of Italy”.

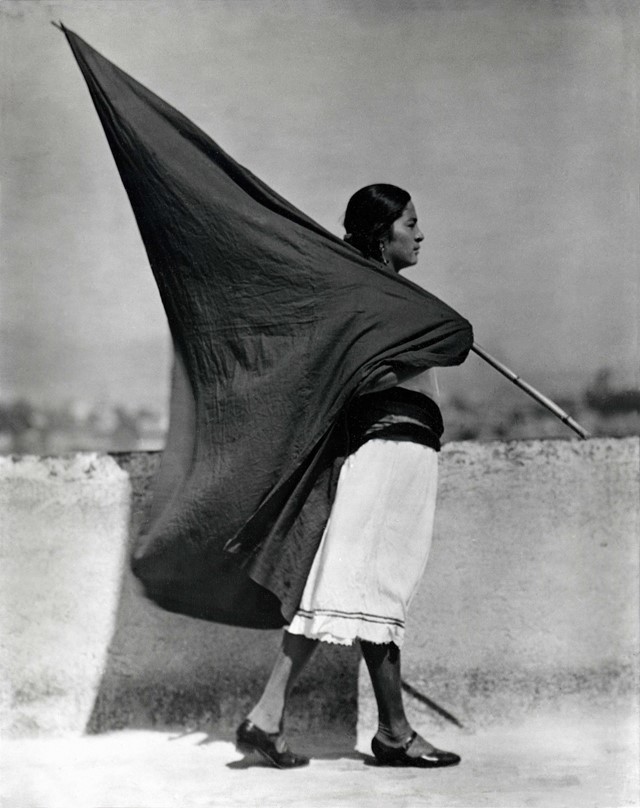

In the spirit of her left-wing politics, she used the camera to compassionately document and give dignity to the working classes, as seen in works like Workers Parade (1926) and Woman from Tehuantepec (1929). Like her contemporary Imogen Cunningham, Modotti turned her lens towards botanical subjects. According to the authors of Tina Modotti, this allowed her to play “with the compositional possibilities of lines.”

Until recently, Modotti’s legacy – like many women artists of that era – has not been adequately documented or preserved. Unjustly, she is often referred to as Weston’s muse, Rivera’s lover or as Kahlo’s best friend (and sometimes lesbian lover – a rumour further cemented by the Miramax film Frida). Ironically, though she has become an obscure figure today, Modotti wielded exceptional artistic and political influence in her lifetime, stretching across the Americas as well as Europe (some even believe she was a Soviet spy). She lived independently and courageously, once remarking: “I don’t believe in marriage. I think at worst it’s a hostile political act, a way for small-minded men to keep women in the house and out of the way, wrapped up in the guise of tradition and conservative religious nonsense.”

Modotti’s life never ceased to be tumultuous. In 1929, no longer with Weston, she fell in love with the revolutionary, Julio Antonio Mella – a founder of the Cuban Communist Party. Tragically, their relationship was short-lived; Mella was assassinated while walking home with Modotti from the offices of Red Aid (the Communist social service organisation). Modotti’s close-up portrait of the deceased Mella features in the publication – his face surprisingly serene despite his violent end.

In a state of exile after 1930, Modotti arrived in Berlin with no possessions and only $400 to her name. She lived precariously and was allegedly trailed by Mussolini’s secret police. She departed Germany for Spain – without documentation – and later voyaged to Moscow, Paris and Spain during the Civil War. Throughout this decade she contributed towards the Communist cause, holding clandestine meetings across Europe and organising anti-fascist action. In 1939, she finally returned to her beloved Mexico, entering illegally under the name Carmen Ruiz Sánchez. And finally, she died at the age of 46, in 1942 while in a taxi on the way to the poet Pablo Neruda's house, in what is still considered to be suspicious circumstances.

Tina Modotti is published by La Fábrica Essentials.