After years of jubilant hiring sprees, luxurious benefits, and florid rhetoric about the value of the people behind the curtain of innovation, the tech industry spent the last eighteen months laying off more than 350,000 of its workers—with more layoffs yet to come. From the outside, this vibe shift may seem abrupt, but workers on the inside have been watching a slow souring of the once outrageous promises the industry offered—both to consumers and to its employees. As internal pushback and unionization have snowballed, tech workers are waking up to the recognition that despite a white collar costume, tech labor is still labor, only at scale. And in the time-honored tradition of American labor, they’re writing about it.

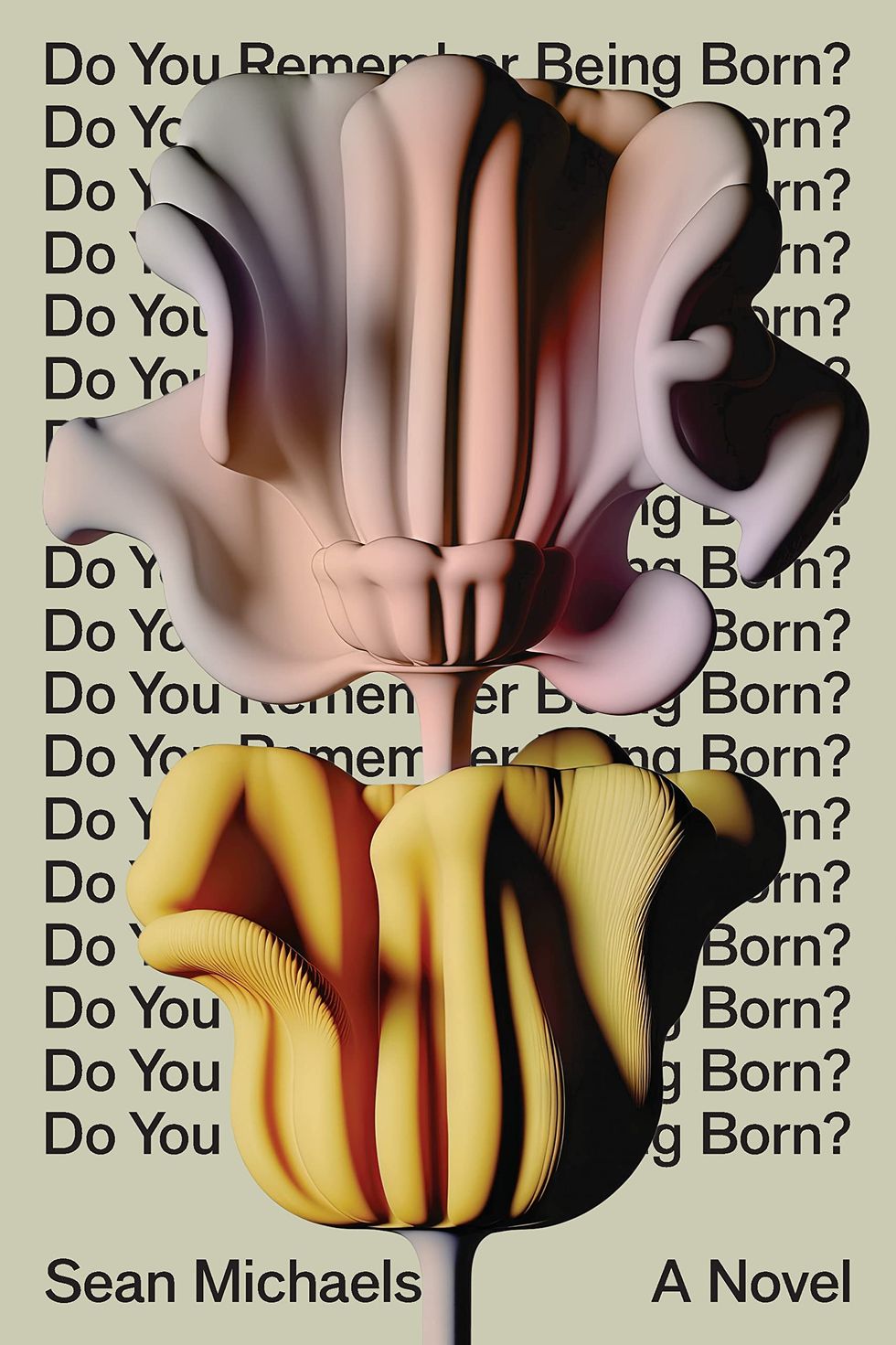

In the last two years, novels from the perspective of tech workers have been popping up like app notifications, many written by former and even current employees. In Sarah Rose Etter’s new novel, Ripe, Cassie is a marketing writer coming to grips with the cruelty of her role at unicorn startup Voyager. In Claire Stanford’s Happy for You, Evelyn is an academic escapee/UX researcher conflicted about building a system to quantify happiness. In Colin Winnette’s Users, Miles has invented an eerie new VR game with unintended consequences, while in Josh Riedel’s Please Report Your Bug Here, Ethan has found a portal in his employer’s photo app that transports a user anywhere and nowhere at once. In Akil Kumarasamy’s Meet Us By the Roaring Sea, a young woman trains an AI called Bogey; in Sean Michaels’ Do You Remember Being Born, a 75-year-old poet wrangles one named Charlotte.

More subtle and internal than the tales of moustache-twirling (or turtleneck-wearing) founders appearing in journalistic profiles and documentaries, these narratives detail the personal crises of individuals clinging to paychecks and praise from their employers while struggling to square the promise of their work with the nagging truth of it. These stories, while fictional, ask a very real question about technology and labor today, against a backdrop of economic precarity and social isolation: how many of our values can we sacrifice for a shot at a secure life? In these novels, the conclusion is dramatically clear: to escape their untenable binds, protagonists launch themselves out of the industry, into parenthood, and across alternate dimensions.

The new crop of tech worker novels all tell a coming-of-age story, with protagonists seeking security and purpose as they move toward ever less attainable milestones of adulthood: first jobs, parenthood, financial independence, and the pursuit of happiness. Ethan, the main character of Please Report Your Bug Here, has left college with a mountain of student loan debt and a desire to make a positive impact on the world—as did the book’s author Josh Riedel, who became the first employee at Instagram. “In the 2010s, there wasn’t as much criticism of the tech industry,” Riedel tells Esquire. As a young person seeking a new identity, “It was really easy to fall into the idea of ‘we’re changing the world.’”

Evelyn, the protagonist of Claire Stanford’s Happy for You, makes a similar step towards idealized independence, although at a slightly later life stage. A struggling PhD candidate, Evelyn decides to take a contract tech job for health insurance and the chance to make a positive impact with her work. “The company is tempting for a number of reasons,” Stanford says. “The obvious one is greater financial security, both coming from being a PhD student and reaching a certain point in her life where she wants financial security that increasingly fewer options in the Bay Area are offering.” But like Ethan, Evelyn is also drawn to the work’s potential. Her employer is building an app to quantify and improve happiness, and Evelyn wonders if it could make her happier too.

Promises like these tempt more than just the young. At 75, Marian Ffarmer [sic] in Do You Remember Being Born worries that her choices haven’t added up to a life that can provide for her, let alone for her grown son. Despite her accomplishments as a poet, she accepts a job at The Company after taking stock of her finances and coming up empty. “No poet has savings,” the character laments, “unless they are born to wealth.” Marian is highly skeptical of The Company, but in addition to the money, she’s intrigued by the gig’s promise to paint a new sheen of relevance across her quiet life.

Money and meaning pull strongly on these tech workers because they are already lacking—Ethan, Evelyn, and other protagonists all long for the sense of wholeness that they understand to be a hallmark of adulthood. In Ripe, Cassie walks around with what she describes as a literal black hole inside her, pulling her toward self-destruction and depression. In Users, Miles hears accusatory ghosts in the walls and worries that he isn’t able to be a proper husband or father. When Evelyn interviews for her tech job in Happy for You, she tries to make herself look like “a real person”—someone she knows herself not yet to be.

The tech workers in these novels are suffering from the infantilization that this moment in late-stage capitalism forces on so many real-life workers—even tech workers, despite outsized salaries and benefits. “Many of the young workers in the industry have large student debt and are living in cities with very high housing costs, with multiple roommates,” says Ben Tarnoff, co-editor of Voices from the Valley, an anonymized collection of tech workers’ accounts of their experiences working in the industry. “It may sound ridiculous, but even those who are earning relatively high salaries may find it difficult to imagine themselves securing a stable foothold in the middle class.”

In fact, all across the globe, far fewer millennials have been able to make it to the middle class than previous generations, while Gen Z is facing an even steeper challenge. Earnings have stagnated—especially in creative fields where many of these fictional protagonists (and their authors) began—while housing prices and costs of living have soared. As she was writing her novel, Stanford thought about how the trail to stable adulthood has gotten steeper, especially for people of color like Evelyn in Happy for You. “A lot of my friends and I are grappling with these feelings of how to achieve independence and, quote unquote, adulthood, when so many systems are stacked up against us,” she says. “How does that ripple out into decisions that folks have to make?” In real life as in fiction, the first step towards tech is about the basics, like healthcare and a steady paycheck, as often as it is the golden handcuffs, like catered lunches and stock options.

Etter, the author of Ripe, notes that when she arrived on the job market without a family-funded safety net, the tech industry looked like one of the most stable options out there—if not the only one she was qualified for. “It's very easy to make jokes about tech workers,” she says. But since the 1990s, tech has been one the few growing U.S. industries. Even now, with layoffs and strategic pivots, tech businesses remain relatively strong. “If we want to talk in real terms about financial stability—especially [for] women and people of color—I don't think it’s that funny of a joke,” Etter says. She sees her novel, a dark meditation on the pain we all carry as we travel through life, as “a way of gesturing towards the powerlessness that I think most of us feel when we think of the economy collapsing and the jobs that we end up in.” She still works in the tech industry, now as a Senior Manager of Content Design.

Like most coming-of-age stories, these novels chart a path from naiveté to self knowledge, crashing against the rocks of complicity along the way. In Meet Us by the Roaring Sea, the unnamed protagonist begins with a logistical decision to work in “only a partially exploitative system, with health insurance benefits,” and ends up wrestling with technology’s impact on humanity. In Ripe, little by little, Cassie takes steps toward an actively manipulative role at the company, plotting to destroy a competitor and hiring a contractor under false pretenses. Then, she must struggle with who she has become. In Users, Miles also faces his own complicity when his game turns out to be a comfortable home for abusive community behavior. In Please Report Your Bug Here, Ethan moves back and forth between separating and aligning himself with his employer. He responds to a friend’s text with copypasta from PR boilerplate, and refers to the company itself as “we” before finally breaking away.

In writing Users, Winnette wanted to dive into questions of complicity through Miles—a character who is part of a system, not the creator of it. We’ve all seen the stark headlines of founders who lied and schemed to push their own agendas. But what about the employees behind the scenes? “If you partake in a system that is flawed, to what degree are you complicit? And to what degree are you just surviving day to day?” Winnette says. “Sometimes I look at Miles and see a total monster.” But other times, Winnette doesn’t know what else the character would do in the situation where his family depends on him. Ultimately, “his problem is his inability to accept responsibility for his own actions,” Winnette argues. Eventually, that drags Miles away from his family, further inside his own pain and the VR machine he’s contributed to.

Other protagonists choose to act in their better (or at least more messy and human) natures. In Happy for You, Evelyn decides to have a baby and return to her PhD program, a complicated path without the binary clarity of the happiness app she’s working on. “For her to regain individual agency in that way and decide to leave the tech company, despite all of its comforts and security, and go back out into a world of uncertainty and complexity, it’s a big move,” Stanford says. The unnamed protagonist of Meet Us by the Roaring Sea becomes pregnant too, and while the novel doesn’t clarify whether or not she will keep the baby, that may ultimately be the point. The character finds peace in partnership with her friend and lover, Sal, and imagines the child living with them, unsure of the future but comfortable with the complexity of the present. Please Report Your Bug Here is framed as Ethan’s own NDA-breaking public accounting of his employer’s grave missteps, which left at least one person lost forever in another dimension. Like Evelyn, he too leaves tech for a more human and humane way of existing in the world, grounding himself in the physical surroundings of San Francisco rather than rushing past his home on a chartered bus towards a technological future.

But are there escape hatches for concerned tech workers that don’t require birthing another human or leaning into epiphany? The word “less” comes to mind when reading these stories: once they got a foot in the door, could the characters want less, give less, expect less from work? Can any of us choose less in the hyper-capitalistic culture that equates productivity with morality, and that seems to have learned so little from the recent years of collective illness and isolation?

Journalist Simone Stolzoff, a former tech worker himself, suggests that doing less could inoculate workers from the unique alchemy of temptation and torture that the tech industry has helped mold into a defining feature of the modern workplace. “‘Good enough’ is an invitation to choose what sufficiency means—to define your relationship to your work without letting it define you,” Stolzoff writes in The Good Enough Job, his examination of how America arrived at this work culture and how we get ourselves out. The protagonists in this batch of tech worker literature are “workists,” by Stolzoff’s definition, conflating the success of their projects with their own moral ascendance. Discovering that employers are less-than-perfect is an inevitable plot point in any career. But for these fictional tech workers, it is a crisis that demands a choice beyond quitting or staying. To feel satisfied, safe, and maybe even happy, they must excise the capitalist more-monger inside them. And for some, like Miles and Cassie (who takes a desperate leap into an ending that is nearly impossible not to spoil), that surgery proves impossible to elect. But there’s still time for real-life tech workers to make their own choices.

Although many of these authors drew on their lived experiences in the industry, fiction allowed them to tell emotionally true stories about this critical moment for tech work culture. Riedel, for his part, sought to capture the feeling of working in tech, not the facts. “There had been nonfiction books that explained a company’s trajectory, but I didn't feel like there were a lot of books that captured the emotional experience of working in Silicon Valley,” Riedel says.

Winnette also drew from an emotional place to capture the anxiety of a man torn between work, family, and his own desire to be loved as the consequences of his efforts spiral out. “The surreal stylistic decisions in the book are meant to evoke that feeling of living in a reality that feels more porous and shifting than it once did,” Winette tells Esquire. “And the alienation, majesty, and horrors of it are beautiful and terrifying at the same time.” Kumarasamy also dabbles in surrealism, fragmenting the narrative in Meet Us By the Roaring Sea across different timelines and voices. The effect is a simultaneous speeding up and slowing down, a collapsing of multiple worlds into one space—not unlike the way technology is uniquely capable of exposing us to everything, everywhere, all at once.

Fiction also allows writers to balance the record, spotlighting tech workers rather than founders, and complex personalities rather than clichés. “A lot of the stories about tech in the media are so founder-focused, and so obsessed with money,” says Riedel. “At least in the past, there wasn’t a lot of discussion of what it was actually like for the majority of people in that industry.” In Ripe, Etter wanted to talk about the nuances of tech work beyond the judgment she often felt from her friends in other industries. “[Fiction] gives you a chance to look beyond the stereotype of the industry,” she says.

Within those nuances is where Winnette finds one of the most beautiful qualities of fiction: the fact that a novel is always a leaky boat, with holes of logic or background that “leave room for the reader to shade the act of communication.” Tech workers are not the only individuals experiencing the impacts of tech work or workism, and fictional stories gracefully extend these deeply personal narratives toward the conflicting and confusing ways that technology and labor have become enmeshed in the world we all inhabit.

Dystopian narratives in particular can offer the opportunity to imagine a better way forward. “When different structures that rule us fall apart, what's new that can emerge?” Kumarasamy says. “Dystopian fiction asks us to uncover who we really are, questioning how we engage with the people and things around us.” In their brutal depictions of worlds driven by ruthless pursuits of profit and uncontrollable tech, this collection of tech worker novels asks us to consider, “Where do we go from here?”

Publishing cycles are long, meaning that the novels hitting shelves now were born during the height of the pushback against tech in 2016, when labor organizers mobilized at big giants like Google and Amazon, and tech work saw the bloom come off the rose both within and without the industry. These novels are intimate and moving examinations of the possibilities for a single worker, struggling to gain a sense of belonging and self-possession within a culture that pushes towards easy answers, even when they’re not the right answers.

The next group of narratives from the tech trenches may look very different. From the Great Resignation to quiet quitting to the layoffs of the last two years, tech workers are making different decisions—and having decisions made for them, too. “There’s a consciousness within large segments of the rank and file within the industry that’s different from a decade ago,” says Tarnoff. “I think that has to do with the residue left by the organizing efforts of the big firms and the mood of the so-called techlash. It has changed how many tech workers think about their work in a permanent way.” Today’s tech work is not veiled by glossy promises and comfortable benefits, and the workers who choose to stay or join the industry are fighting for collective power as well as individual agency, with their eyes wide open. Perhaps the era of workism is waning.

The writers may be different too, as more voices push against ongoing bias in both the tech and publishing industries. “I certainly would like to see more BIPOC tech stories,” says Stanford, who is biracial herself. “It’s very shocking how few there actually are when everyone's body and mind are on the line in this discussion.” Riedel hopes to see new professional perspectives represented in fiction, as well—the kinds of roles that are not usually highlighted within tech, like warehouse workers and cafeteria chefs. “Who drives the Google streetview car around?” he wants to know. “And what’s it like to get flipped off all day long?”

But the uncertain and stratified world in which the tech industry has thrived continues to march forward toward ever-later-stage capitalism. Amid ongoing labor strikes, hyper-accelerating AI development, and an economy locked into a will-they-or-won’t-they storyline with a recession, any happy path for worker security remains blocked by existential compromise. “We exist in a place where, without your own hunger to take care of yourself and the people in your life, there isn’t a lot to rely on,” says Winnette. “The country is not providing for you; you’re on your own.” However, these tech worker novels make clear that piling good intentions into the shape of financial security may only make the problem worse. “The more you accumulate, the more you start to fear absence,” says Winnette. However tempting its pitch, more labor cannot keep us safe.