Killing of Iranian general marks huge gamble by Trump

In ordering the killing of Gen. Qassem Suleimani, one of Iran’s highest-ranking officials, President Trump took one of the biggest gambles of his presidency — a step that appears to lead the U.S. on a path toward escalated warfare and that marked a sharp break from his often-stated desire to pull American forces out of conflicts in the Middle East.

Throughout his presidency, Trump has made fiery statements but has typically resisted dramatic belligerent actions. He has promised his supporters that he would use decisive violence against U.S. enemies, but he also promised to stay out of wars in the Middle East and to bring U.S. troops home.

Outside analysts — and some of Trump’s former advisors — have repeatedly warned that those two pledges could not be reconciled.

Until now, when his goals clashed, Trump has typically pulled back. In June, for example, he gave a last-minute order to stop an airstrike against Iran planned in retaliation for Tehran’s shooting down of an unmanned American drone. Nor did he order a military response to attacks on Saudi oil installations in the fall that U.S. and Saudi officials blamed on Iran.

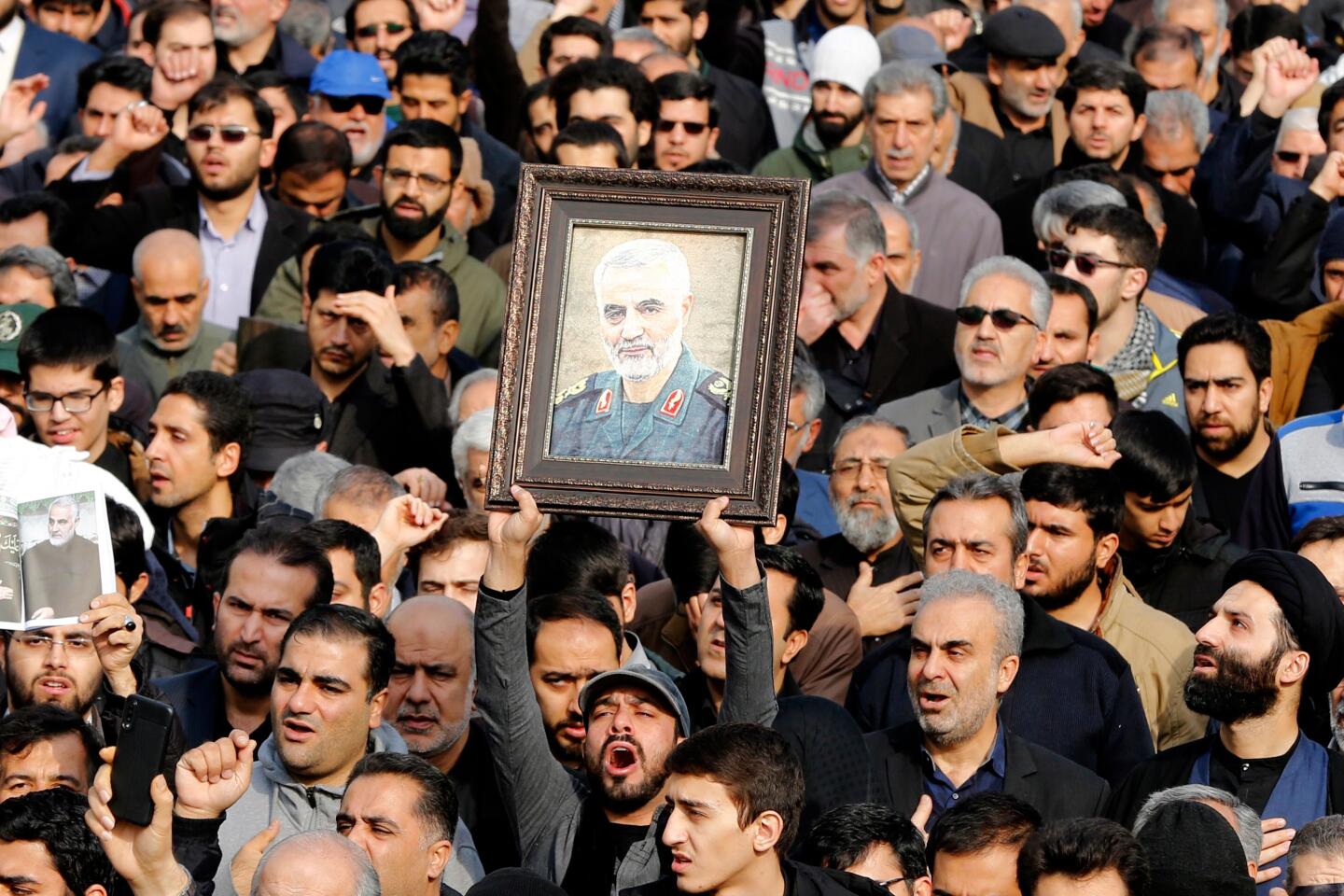

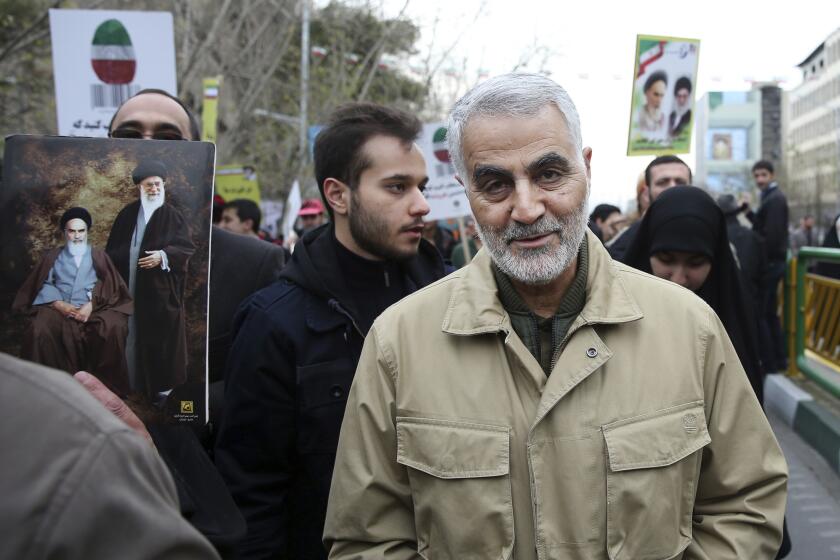

The decision to kill Suleimani, the head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ elite Quds Force, who was sometimes described as the second-most powerful official in Iran, radically shifted Trump’s approach. The decision appeared to reflect a bet that Iran, faced by a decisive U.S. military action, will back down, not escalate.

Iranian Gen. Qassem Suleimani, the head of Iran’s elite Quds Force, has been killed in a U.S. airstrike at Baghdad’s international airport, according to the Pentagon.

Iran will now have to “reexamine the limitations of the violence they can bring to the table,” said one senior congressional Republican official, speaking on condition of anonymity. The official predicted “some face-saving retaliation in Yemen or Lebanon, maybe Afghanistan,” but not more.

Others were deeply skeptical of such assertions. While the U.S. undoubtedly has overwhelming superiority in conventional military power, analysts warned that the Iranians, even without Suleimani, will be able to launch guerrilla-style operations throughout the Middle East and possibly beyond. Previous attacks blamed on Iran or Iranian proxies have spanned the globe from Latin America to South Asia. Cyberattacks targeting U.S. infrastructure or businesses also remain a concern.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said in a statement that “a harsh retaliation is waiting.”

“The U.S. and Iran have been engaged in a dangerous tit-for-tat for months now, but this is a massive walk up the escalation ladder,” said Charles Lister, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute in Washington. “There really is no underestimating the geopolitical ramifications of this.”

Trump’s decision will also be a test for his credibility, which has been worn paper-thin by years of lies, evasions and misstatements in domestic and international affairs.

His administration said Suleimani was killed because he was plotting to kill Americans, but officials have not provided proof of what Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo described as an “imminent attack.”

In addition, critics have warned that Trump has hollowed out Washington’s normal process for analyzing national security issues, making it less likely that officials have considered all the angles and prepared for potential blowback.

U.S. officials have blamed Suleimani for masterminding attacks on American forces in Iraq and Syria for years. Both the Obama and George W. Bush administrations considered killing him but stopped short, judging that the risks of an escalated conflict outweighed the benefits.

“What always kept both Democratic and Republican presidents from targeting Suleimani himself was the simple question: Was the strike worth the likely retaliation, and the potential to pull us into protracted conflict?” said Rep. Elissa Slotkin (D-Mich.), a former CIA analyst and expert on Iraq’s Shiite militias who served in Iraq and as a senior Pentagon official.

“The two administrations I worked for both determined that the ultimate ends didn’t justify the means. The Trump administration has made a different calculation,” Slotkin said.

In brief remarks Friday from his Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida, Trump shed little light on why he had made that choice. He suggested he had authorized the killing of Suleimani after U.S. officials detected a plan for a new attack.

“We caught him in the act,” Trump said. Like other officials, however, he offered no evidence to back up that assertion.

To heighten the political risk, Trump appears to have acted without advance consultation with Congress, breaking with long-standing practice. The lack of any such briefing reduced, if not eliminated, the chance of bipartisan support for such a sensitive operation. Congressional Democrats quickly criticized the president for acting unilaterally.

“The Administration has conducted tonight’s strikes in Iraq targeting high-level Iranian military officials and killing Iranian Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani without an Authorization for Use of Military Force against Iran. Further, this action was taken without the consultation of the Congress,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) said in a statement a few hours after Suleimani’s death was confirmed Thursday night.

“The full Congress must be immediately briefed on this serious situation and on the next steps under consideration by the Administration,” she said. “We cannot put the lives of American service members, diplomats and others further at risk by engaging in provocative and disproportionate actions. Tonight’s airstrike risks provoking further dangerous escalation of violence.”

While U.S. forces have killed leaders of Al Qaeda and other militant groups, targeting high-ranking officials of other governments has been a line that American officials have seldom crossed except during wars.

Not since President Reagan ordered an airstrike against Libya in 1986 that came close to killing that country’s leader at the time, Moammar Kadafi, has the U.S. taken an action comparable to the attack on Suleimani.

In an extraordinary interview on live radio this week, Donald Trump seemed to stumble when he landed in the Middle East.

Suleimani has long directed the actions of Iranian-backed militia groups that have attacked U.S. forces in Iraq and elsewhere, and administration officials said he was planning further attacks on American personnel.

“Gen. Suleimani was actively developing plans to attack American diplomats and service members in Iraq and throughout the region,” Defense Secretary Mark Esper said in a statement. “This strike was aimed at deterring future Iranian attack plans.”

Critics, however, accused Trump of recklessness.

“President Trump just tossed a stick of dynamite into a tinderbox,” former Vice President Joe Biden said in a statement.

“He owes the American people an explanation of the strategy,” added Biden, a leading Democratic presidential candidate.

“No American will mourn Qassem Soleimani’s passing. He deserved to be brought to justice for his crimes against American troops and thousands of innocents throughout the region. He supported terror and sowed chaos,” Biden said.

But, he added, “this is a hugely escalatory move in an already dangerous region.”

The immediate chain of events leading to the strike began late in December when a missile attack against an Iraqi military base killed an American contractor. U.S. officials blamed the attack on Iranian-backed militia groups and responded with airstrikes that killed 25 people.

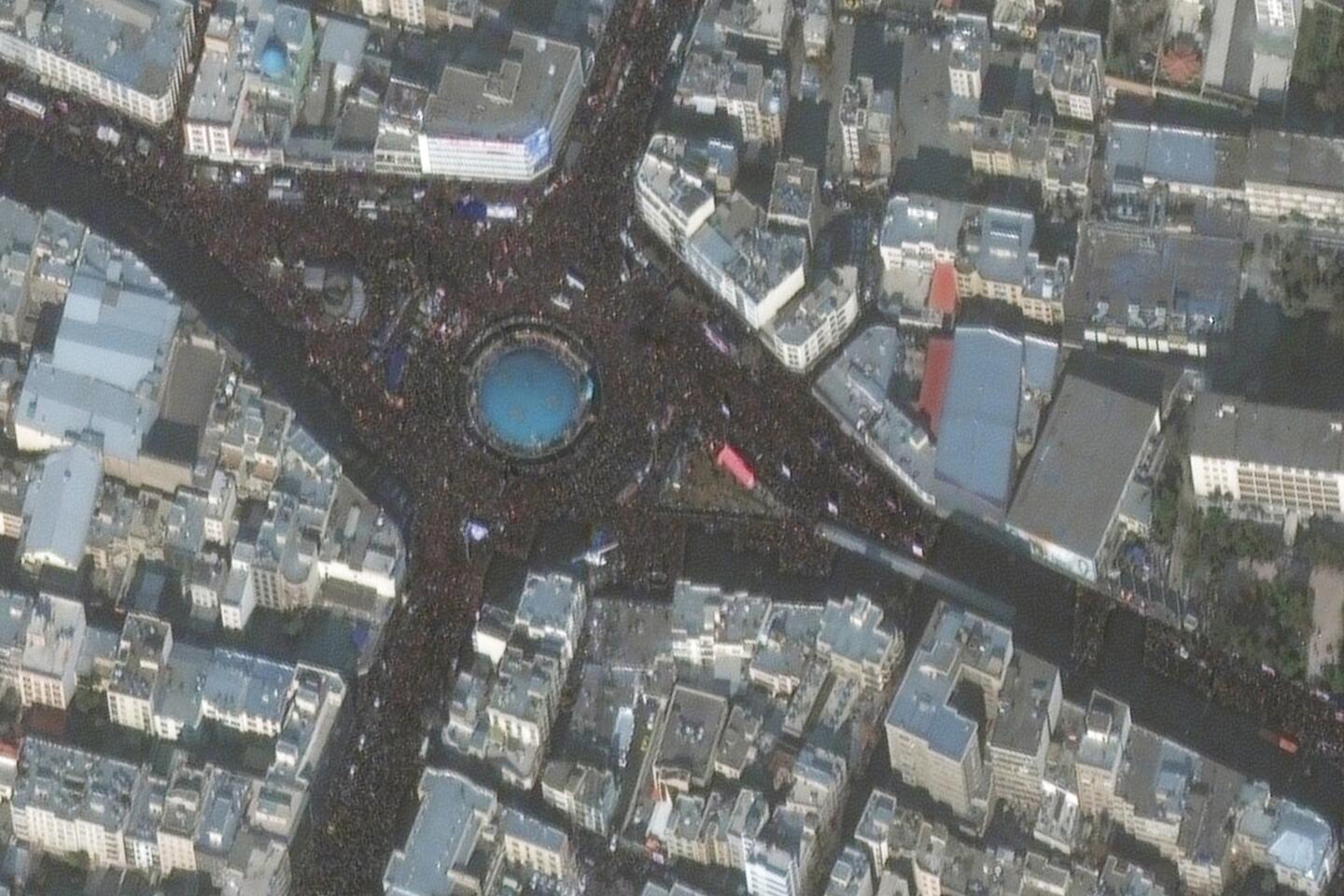

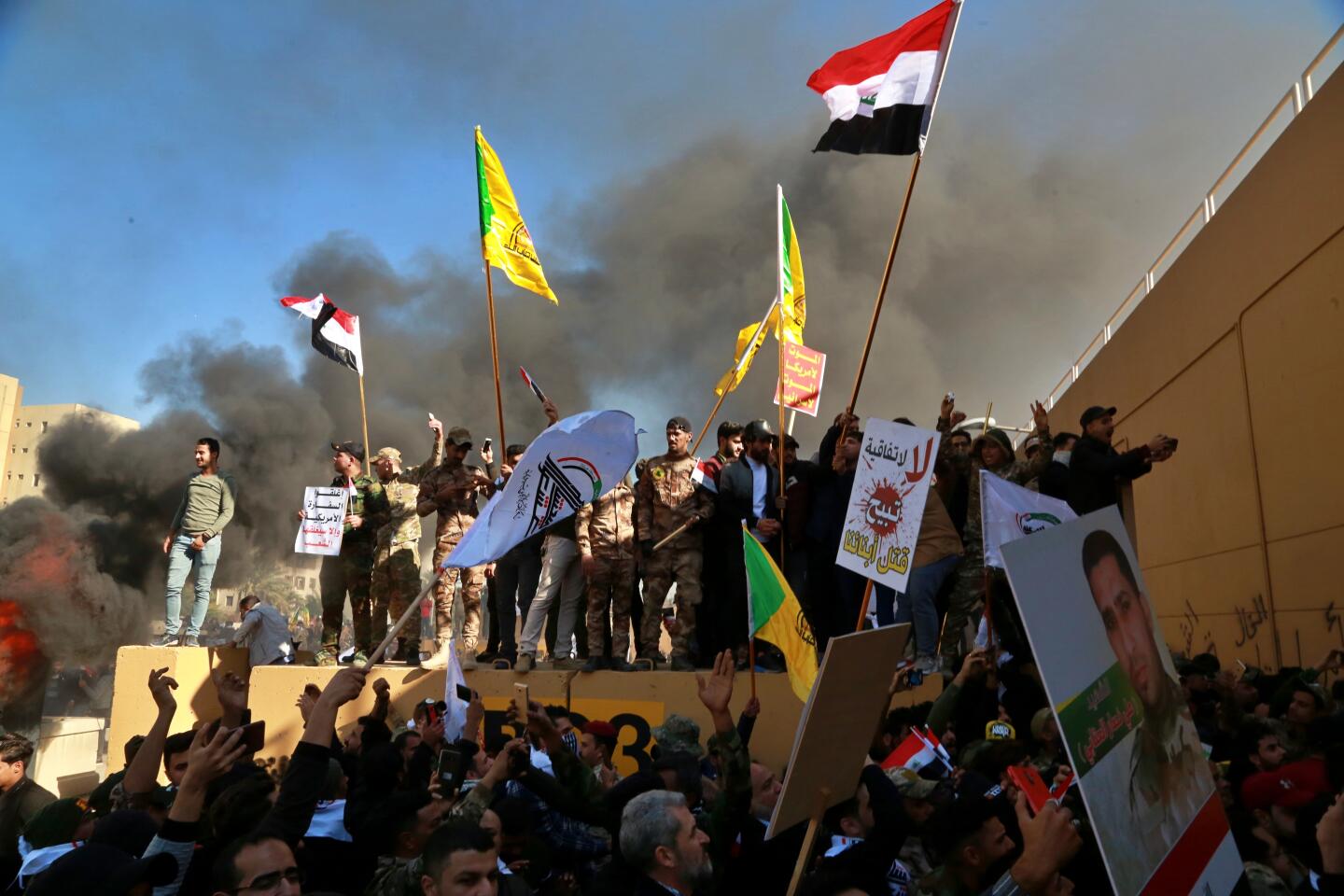

That, in turn, led to the storming this week of the U.S. Embassy compound in Baghdad by pro-Iranian militia members. At that point, a senior administration official said Thursday, the “game has changed.”

Long symbols of American might and influence, embassies and consulates have been vulnerable for decades. Diplomats say Trump’s politicization of the attack hasn’t helped.

Administration supporters said the strike would be a major setback to Iran.

Suleimani’s “death is a huge loss for Iran’s regime and its Iraqi proxies, and a major operational and psychological victory for the United States,” said James Carafano of the conservative Heritage Foundation, which often advises Trump on foreign policy.

Ariane Tabatabai, a Middle East expert at Rand Corp., said the killing of Suleimani sent a strong symbolic message to Iran and its allies, though it won’t lead to the collapse of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps or Iran’s network of non-state allies.

From Afghanistan to Lebanon and Yemen and Syria, he played a key role in building Iran’s network of allied groups across the Middle East, which included Shiite militias in Iraq and groups such as Hezbollah in Syria and Lebanon, she said.

Suleimani was a major figure in the highest levels of Iranian decision making, reporting directly to the supreme leader and overseeing military training and financing as well as weapon sales and transfers. He also took a highly public role as an Iranian symbol, often photographed on regional battlefields to underscore Iran’s support for its allies.

“He would run around the battlefield in Syria and talk to the fighters and try to boost their morale,” Tabatabai said.

One Senate Democrat asks: “Did America just assassinate, without any congressional authorization, the second most powerful person in Iran?”

But though Suleimani has a long history of orchestrating relationships with Iran’s proxy groups, he did not act single-handedly, said Suzanne Maloney, an Iran specialist at the Brookings Institution.

“He is a major figure that earned a reputation as an effective strategist ... but we have to be careful not to suggest that his death would inevitably degrade Iran’s capabilities,” Maloney said.

“This increases chance of violence,” she added. “Shiite militias in Iraq will use it to their own advantage.”

Wilkinson and Megerian reported from Washington and Etehad from Los Angeles. Times staff writers Eli Stokols and Jennifer Haberkorn in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.