In 2016, William Gibson was a third of the way through his new novel when Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. “I woke up the day after that and I looked at the manuscript and the world in which the novel was set – a contemporary novel set in San Francisco – and I realised that that world no longer existed. That the characters’ emotional basis made no sense; that no one’s behaviour made any sense. Something of this tremendous enormity had just happened and I felt really lost – and sort of mournful. I was losing this book.”

The great chronicler of the future had been overtaken by events. This had happened once before. Gibson had been 100 pages into Pattern Recognition – the first of his novels set in a near contemporary version of reality – when the Twin Towers fell, forcing him to rewrite that novel’s world and the backstories of its characters. His future had to catch up with the present.

That said, Gibson’s futures have always got a little tangled up with the present. Probably the most influential living writer of speculative fiction, his best known aphorism is “the future’s already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed”. Two or three generations of readers have now seen the futures he envisaged in his three trilogies of novels coming dismayingly into being around them. Virtual digital spaces, artificial intelligence, corporations superseding nation states, extreme body modification, and the insane metastasis of the marketing and branding industries ... Gibson was on to all these things when Black Mirror’s Charlie Brooker was still in short trousers. And his influence endures. Just last week, Dominic Cummings – a fan – referenced Gibson’s character Hubertus Bigend in a Downing Street job advert.

This latest twist in reality – Trump’s election – meant Gibson had to go to back to the drawing board with the new book, just as he had with Pattern Recognition. For a long time he didn’t think the book that was to become Agency could be salvaged. He went through “at least two hard publishing deadlines” as he tried to find a way of bringing it back to life. He had his heroine, Verity, and her encounter with Eunice – the AI entity around whom much of the novel’s plot revolves. But how could he make them fit into a post-Trump world?

“I thought, you know, this is never going to happen. And it really threw me – for about six months. All I could do was read the news feed and feel worse about that. But eventually I realised that I wanted to believe I was living in a stub. That something had split off and that things weren’t supposed to be this way. It wasn’t supposed to be as dire. And having had that passing thought, I thought – wait a minute! Verity is in a stub. And suddenly it worked. I had a framework that was coming together.”

He retconned, in other words, what was originally intended to be a standalone work into something that is now more straightforwardly a sequel than anything else in his canon. Agency reprises the setup and many of the characters of his last book, The Peripheral. That novel – which, fans of Gibson’s strangely little-filmed canon will be pleased to hear, is about to be adapted for Amazon Prime by the team that made Westworld – is set between a London of the early 22nd century, after an unspecified apocalypse called the Jackpot has wiped out 80% of the population, and a near future town in rural America. As we discover, the latter is a “stub”: an alternative timeline in which technologists (and, more tellingly, hobbyists) of the future are able to meddle. Agency is set between that far future London and another stub – a present day San Francisco where Hillary Clinton won the 2016 election – and describes its protagonist Verity’s relationship with the dizzyingly powerful Eunice as they attempt to avert that stub’s version of the civilisation-ending Jackpot.

“My specific time travel gimmick in these books,” Gibson says, “is that it’s impossible to physically visit the past, so you have to do it digitally. But immediately on contacting the past you create a stub, because that contact didn’t happen in your past so you create an alternate history. And that spares me all of that tedious paradoxical stuff that bogs down time travel stories.” He pinched a version of the idea, he’s generous enough to acknowledge, from Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner’s 1985 short story “Mozart in Mirrorshades”.

As a Canadian writer who initially marked his territory in a future Japan, what attracted him to setting his post-Jackpot world in London? He doesn’t see it as so much of a jump. “On my first three or four visits to Japan I immediately thought that Tokyo had more in common with London than with any other city,” he says. “These disproportionately large sites of former empires, huge concentrated populations, recent wartime trauma, lots of fatalities. They’re capitals of island nations. But also cultural things: the fanatical attention paid to specific individual classes of objects. In London you could probably find a speciality shop for almost anything. And you certainly could in Tokyo. All these parallels. I’m curious that I’ve almost never seen it mentioned anywhere.”

In a way Gibson came to fiction late. Born in South Carolina, steeped in William Burroughs and Henry Miller, he dropped out of high school and spent his late teens and early 20s travelling and experimenting with drugs and the counterculture. When he “washed up” in Canada in the 1960s – initially, he claimed to have been dodging the Vietnam draft – he ran Toronto’s first “head shop”. In the mid 70s, having started a family, he went to university to study English literature – and what he learned there helped to rekindle his childhood interest in writing science fiction, which was properly kickstarted when he fell in with John Shirley, Shiner and Sterling.

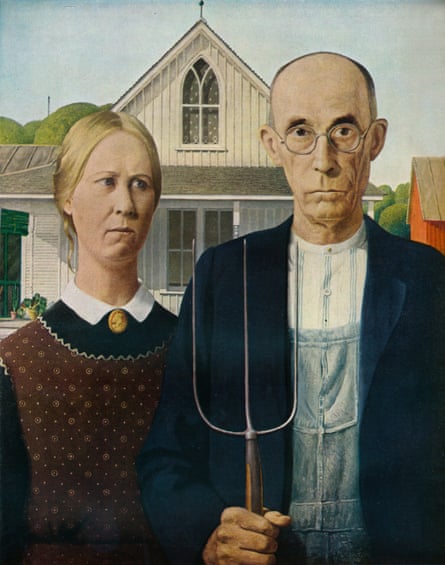

It’s a happy accident that, at 71, Gibson looks like a more benign version of the pitchfork-toting male figure in Grant Wood’s painting American Gothic. His 1982 short story “Burning Chrome” is credited with popularising the term “cyberspace” (“A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts ... A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding”). His 1981 short story “Johnny Mnemonic” was made into a film starring Keanu Reeves in 1995, but Gibson’s breakthrough only came with 1984’s Neuromancer. He famously wrote this rip-roaring, noir-inflected fantasy of burned out hackers and technologically augmented ninjas – which gave birth to the whole “cyberpunk” genre – on a manual typewriter, and he freely talks of himself as a late adopter. So maybe the poetic, rather than technological, turn in that description of cyberspace is the way to read him. He magpies futuristic sounding stuff.

“I was actually able to write Neuromancer because I didn’t know anything about computers,” he says. “I knew literally nothing. What I did was deconstruct the poetics of the language of people who were already working in the field. I’d stand in the hotel bar at the Seattle science fiction convention listening to these guys who were the first computer programmers I ever saw talk about their work. I had no idea what they were talking about, but that was the first time that I ever heard the word ‘interface’ used as a verb. And I swooned. Wow, that’s a verb. Seriously, poetically that was wonderful.

“So I was listening to it as an English honours student. I would take it back out, deconstruct it poetically, and build a world from those bricks. Consequently there are other things in Neuromancer that make no sense. When the going gets really tough in cyberspace, what does Case do? He sends out for a modem. He does! He says: ‘Get me a modem! I’m in deep shit!’ I didn’t know what one was, but I had just heard the word. And I thought: man, it’s sexy. That really sounds like it could be bad news. And I didn’t have anybody to read it and … I couldn’t Google it.”

Actually, he acknowledges later, “I think Google’s changed my writing a bit. I now realise that anyone who’s seriously into the text is going to be Googling everything as they go along – or anything that strikes their eye. It actually adds a different level of responsibility. I can’t be quite as random now.” He has to ensure that the made up stuff is definitely and securely made up, and that the real, Googleable stuffis accurate.

Gibson is active on Twitter as @greatdismal, though joining it wasn’t an obvious Gibson move. He initially expected to spend five minutes or so on the site, hence the odd handle: he happened to have been reading a history of the Great Dismal Swamp, near his childhood home in Virginia, when he created a temporary account.

“I’m sort of glad though that I didn’t have @realwilliamgibson or something,” he says, “because it doesn’t get me what I’m interested in. It’s nice to see people react to one’s work but what I want is information that I wouldn’t be able to get anywhere else. Back when I was writing the early books I’d go to this wonderful shop in Vancouver where I’d buy $300-worth of foreign magazines – like Japanese fashion magazines – and cart it all home and pile it beside my desk. What I was paying all that money for was a stack of curated novelty from global sources. And as soon as I had Twitter I had more curated global novelty than I could ever access.

“Pretty soon the newsstand closed – not because I wasn’t supporting it, but that had something to do with it. When you had to buy an actual hard copy of Gothic & Lolita Bible to find out about the Gothic Lolita subculture, it’s really something. It felt really special because, you know, your next door neighbour wasn’t going to find it on Twitter.”

Gibson has said in the past that he’s more interested in writing about the human reaction to technology than technology itself. And what started him writing SF as an adult was that missing human element: “What the science fiction of my youth generally seemed to lack was … everything that made literary naturalism a radical proposition.” In his early teens he’d devoured mid-century American SF such as Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov. When he got older – in distaste for the reactionary politics and “its assumption of a world that’s basically entirely American, a whole universe that’s entirely American” – he turned his back on that, reading British new wave (JG Ballard, M John Harrison) and getting his American “science fiction vitamins”, as he puts it, from Thomas Pynchon and Kurt Vonnegut.

So when he returned to SF at college, “It was as though I had been present at the birth of Nashville swing and gone back looking for it and found the Nashville of the early 70s,” he says. The disappointment was galvanising. “It helped to form the idea that, you know, maybe I could actually do that.”

Thus, as much as his books are populated with nanotech assemblers, haptic recon commandos, gunpacked ceramic Michikoids and all that sort of malarkey (he admits to being “loosey goosey” with the science), they aren’t weightless fantasies. His characters eat, and have love lives and in some cases have kids and spend most of the novel looking after them. Wilf – a principal protagonist in the future London of The Peripheral – spends most of Agency babysitting: “As the narrative went on I realised that what he mostly needed to do was mind the baby – otherwise he’s going to have to leave it with the nanotech pandas. And, you know, that’s the naturalistic part of it. That’s life.”

One character suffers something we’ll all recognise – a “momentary pang of phonelessness”. And, hilariously, Agency prominently features a kickass combat drone – like a sort of R2D2-size Swiss Army deathknife, but the heroes have to spend the whole time lugging its battery pack and charger around after it. “That’s a part of my kit as well,” says Gibson, patting the smartphone resting on a spare battery pack by his coffee. “I don’t want people to forget about the charger. You’re lugging it around. You’d be lost without it.”

The lazy shorthand with which he’s sometimes described is as a prophet. How does he feel about that? An albatross around the neck, an encouraging compliment – or just part of the job? “It’s actually ... It seems to be a thing. But I’ve been discounting it actively throughout my entire career. I don’t think you could find a single interview with me in which I don’t make the point that I’ve got it wrong easily as often as I’ve got it sort of right.”

He certainly gets it right in one respect in Agency: the flashpoint crisis in the book’s contemporary timeline concerns a Turkish invasion of northern Syria, complicated by Russian interference, after the US pulls out. The book would have been at the proof stage by the time Trump announced his withdrawal from the region last year.

“The person who designed that crisis,” Gibson says, “is someone with a job in government in the United States. He’s been a very good friend for quite a while, and given his professional background, I knew that he could give me something. I didn’t specify that part of the world. I just said I need a Cuban missile crisis-like event that could happen now. He came up with that one almost immediately. What’s been very eerie for me is seeing the actual place names I used on the news. I wrote to him immediately. He said: ‘Well why do you think I put it in there? If that sort of thing happens it’s going to happen there.’” Subcontracting crisis design, it bears noticing, is an extremely William Gibson thing to do.

Does it matter to try to get it right, though? “Every fiction about the future is like an ice-cream cone,” he says, “melting as it moves into the future. It’s acquiring archaism by the second. And I’m sure that Neuromancer, for instance, will ultimately be read for what it tells the future about the past. That’s ultimately all we can get from old science fiction. That’s the fate of antique science fiction. All science fiction eventually becomes vintage – mine included. But I knew that. I knew that before I even started writing it. And I’ve always found it delightful. It’s a delightful thought, as I’m working, that one day this will all just be completely archaic and hokey. But it’s my job to make that take quite a while.” A 13-year-old reader of Neuromancer now, he points out, might well guess: “This is about what happened to all the cellphones. This cyberspace thing exists because something happened to the cellphones.”

And, indeed, Gibson stopped setting his novels mainly in the far future around the turn of the millennium. He changed mode. “Since Pattern Recognition I’ve been writing novels of the recent past. They’ve tended to be published in the year after they actually take place. After the publication of All Tomorrow’s Parties [1999] I had a feeling that my game was sagging a bit. Not that there’s anything particularly wrong with that book – but I felt that I was losing a sense of how weird the real world around me was. Because I was busy writing novels and whatever, and I’d sort of glance out of the window at the day’s reality and I’d go: ‘Whoah! That was really strange.’ Then I’d look back down at my page and realise that that was stranger than my page, and I began to feel … uneasy.”

So he cast around contemporary culture “for the elements of things that I had found sufficiently weird to feel that I was still doing what I had done before”. When readers don’t notice that these books are set in the present day, he says, “This is a good sign. This is what I wanted.”

He adds: “The really scary thing about actual futurity, for me, is the newsfeed of the present day. It’s something I could never have imagined. If it had been pitched to a Hollywood producer a decade ago they’d say: ‘Get outta here, never darken my door. This is ridiculous!’ If I had a little window into 2019 back in 1981, instead of saying, here’s some made up future shit, but what they’re actually showing me is all of this – I’d say some of this is so stupid. I cannot use this clownish, ludicrous behaviour by these ridiculous politicians who are beyond parody. I mean, in 1984 if someone claiming to be from the future had shown me Boris Johnson I’d have told him to fuck off and quit pretending to be from the future.”

The Peripheral and Agency, Gibson says, will definitely be joined by a third novel to form a trilogy. This mechanism for opening an infinite branching universe of possible “stubs”, after all, gives him maximal room for manoeuvre. “I couldn’t prove this, but this is my hunch,” he says. “I think this is what my creative unconscious was doing with Agency and part of why it took so long – to design a sort of universal flexible joint between The Peripheral and an even more actual sequel to it.

“Agency is a sort of connector. It’s universal because it’s designed to cope with anything – whatever is happening in the next few years short of complete nuclear destruction – in which case it won’t matter. For me it’s open-ended in a lot of ways so I’m hoping that what I’ve designed will prevent me from having a repeat of that experience I had on 9 November. That’s what I’ve been trying to build.”

Something future proof?

“Heh, yes. Future proof. But that seems like, you know ... hubris. Major hubris.”