In the summer of 1860, the Harvard botanist Asa Gray published in The Atlantic a sympathetic, though tentative, defense of Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species,” which was then provoking anxiety among theologians and scientists alike.

“The Darwinian theory, once getting a foothold,” Gray wrote, “marches boldly on, follows the supposed near ancestors of our present species farther and yet farther back into the dim past, and ends with an analogical inference which ‘makes the whole world kin.’”

The geologist Louis Agassiz, Gray’s Harvard colleague—and, soon enough, Atlantic colleague as well (the magazine’s masthead at the time being more or less coterminous with Harvard’s faculty roster)—was by then publicly denouncing Darwin. Gray and Agassiz would debate natural selection over the next decade. The Atlantic published Agassiz’s anti-Darwin manifesto, “Evolution and the Permanence of Type,” in January 1874, a month after the geologist’s death. “His concise and effective phrases,” Agassiz wrote, “have the weight of aphorisms and pass … for principles, when they may be only unfounded assertions. Such is ‘the survival of the fittest.’”

Agassiz lost his debate with Gray, of course, and he would lose his reputation as well (he had a distressing tendency to advance theories of racial supremacy and creationism). Gray, who was open to the new, is, in my self-interested opinion, more the Atlantic type than Agassiz, even though Agassiz contributed tens of thousands of words to our magazine, most of them on matters relating to rocks.

Here is one of my favorite passages from Gray’s earth-shaking review—my favorite passage despite (or perhaps because of) its black-hole-density construction:

Wherefore, in Galileo’s time, we might have helped to proscribe, or to burn had he been stubborn enough to warrant cremation—even the great pioneer of inductive research; although, when we had fairly recovered our composure, and had leisurely excogitated the matter, we might have come to conclude that the new doctrine was better than the old one, after all, at least for those who had nothing to unlearn.

Excogitated! Just imagine an Atlantic writer today trying to slip a word like that past our watchful copy editors! The argument embedded in this passage, however—the importance of maintaining intellectual and analytic composure in the face of emotion, obscurantist belief, public pressure, and recalcitrant tradition—represents our magazine at its best.

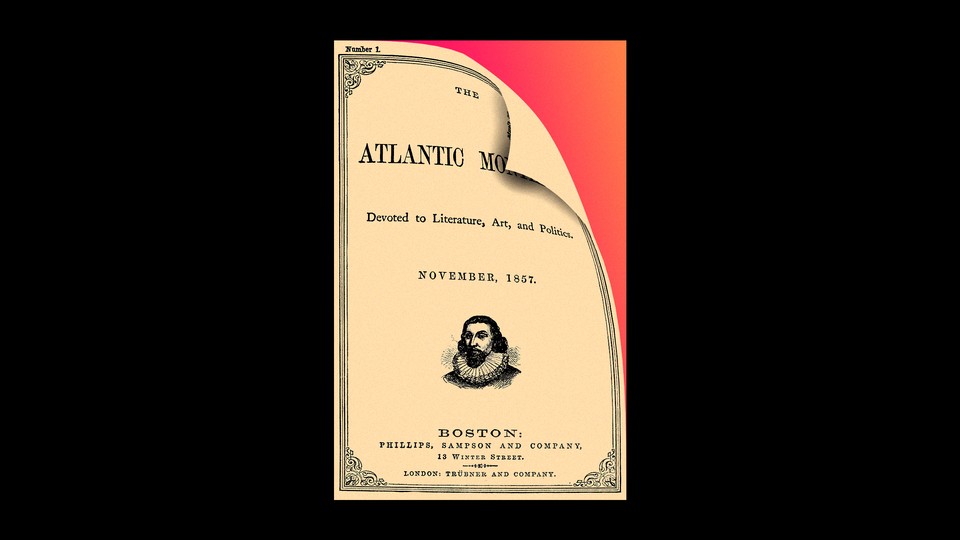

One of my great joys as a journalist here is to spelunk into our physical archive in search of treasures like Asa Gray’s review. And it has been a particular frustration of mine that I could not share the joy with our readers. So it is an enormous pleasure to let you know that we have finally made our full archive—representing 165 years of Atlantic journalism—available online. Nearly 30,000 articles, reviews, short stories, and poems, published between The Atlantic’s founding in 1857 and 1995, the year we launched our website (a site that included, from its start, articles that originated both in print and on the web), are now accessible to subscribers, researchers, students, historians, and that blessed category, the incurably curious.

“The world is all gates, all opportunities,” Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of our founders, said, and the gates to our magazine’s rich past are now open.

I hope that our readers will experience the same wonder I felt when I learned that The King and I, the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, was birthed in the pages of The Atlantic, in the form of a memoir by Anna Leonowens, who taught the Siamese King Mongkut’s 39 wives and concubines, as well as his 82 children. Or when I discovered Felix Frankfurter’s defense of Sacco and Vanzetti, or the rolling argument between Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois on the methodology of Black liberation, or Mark Twain’s first impressions of the telephone, or one of Hemingway’s earliest short stories, or Rachel Carson’s initial foray into nature writing, or Sylvia Plath’s best poems, or Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” (yes, first published in The Atlantic).

You will find, as you explore the archive, luminous, limpid, and polyphonic prose, but I should warn you that you will find opaque and unintelligible prose as well, along with a good number of writers who merit their obscurity. You will certainly find writers who used 15 words when one or two would have sufficed. You will read imperishable poetry, and also eminently perishable poetry. It’s all here: the good, the bad, the brilliant, the offensive, the ridiculous. We knew from the start that we would engage in no censorship, trimming, or dodging. And so you will also find in the archive eugenics sympathizers and people who today would correctly be called racist, misogynistic, imperialist, and anti-Semitic (for instance, I have framed on my wall the cover of our January 1939 issue, which featured a story titled “I Married a Jew,” written by—wait for it—“Anonymous,” a German American woman who wrote, “I frequently find myself trying to see things from the Nazis’ point of view and to find excuses for the things they do—to the dismay of our liberal-minded friends and the hurt confusion of my husband.”) As journalists, we felt it important to share our archive in full, for reasons of transparency and historical accuracy.

To help our readers begin to explore the millions of words we’ve just uploaded to the web, we’re launching a special project spotlighting 25 writers from our past, with essays written by contemporary Atlantic writers. These featured writers include one of the two greatest figures of 19th-century American life, Frederick Douglass, along with Helen Keller, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry David Thoreau, Raymond Chandler, and John Muir. And we’ll keep adding new writers, because the Atlantic bench has infinite depth.

I hope you find our archive illuminating. I leave you with a thought from William Dean Howells, the third editor of The Atlantic, about the man who gave our magazine its name, the physician Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.: “The secret of a man who is universally interesting is that he is universally interested.”

There is a universe of interest in our archive. Please explore!