On the evening of 9 August 1956, a couple of hundred people squeezed into a student union lounge for a concert recital at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, about 130 miles outside Chicago. Student performances didn’t usually attract so many people, but this was an exceptional case, the debut of the Illiac Suite: String Quartet No 4, that a member of the chemistry faculty, Lejaren Hiller Jr, had devised with the school’s one and only computer, the Illiac I.

Decades before today’s artificial intelligence pop stars, Auto-Tune and deepfake compositions was Hiller’s piece, described by the New York Times in his 1994 obituary as “the first substantial piece of music composed on a computer” – and indeed by a computer.

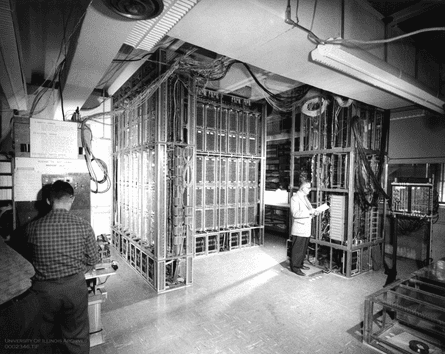

One of the four musicians who performed the piece that night was George Andrix, a violist and composition student at the university. Now 89, Andrix remembers an auditorium packed with people “who showed up to see what this monster of a computer could do.” The Illiac I, short for Illinois Automatic Computer, was the first supercomputer to be housed by an academic institution. “It would have been a big point of pride that the computer was being used in this way,” he says.

The following day, a wire story published by the United Press cast the show, which lasted 15 minutes, in a contentious light. It referred to the piece as “a suite composed by an electronic brain” that was “sponsored” by Hiller and his research associate Leonard M Isaacson. “Some people didn’t dig the beat,” the article claimed, citing one unnamed audience member who likened the music to a barnyard and another who feared “it does away with the need for human composers”.

Hiller, the man primarily responsible for the Illiac Suite, became an overnight celebrity, appearing in Time magazine and Newsweek. “I went from total obscurity as a composer to really being on the front page of newspapers all over the country,” he told an interviewer in 1983. “One week I was nobody, and the next week I was notorious.” Biographer James Matthew Bohn recalls stories of Hiller’s phone “ringing almost off the hook” in the aftermath of the performance. “He was very famous for 15 minutes,” Bohn says.

Sixty five years later, the Illiac Suite has gone back to being largely unknown outside certain classical, experimental and academic circles, but it marked a historic first step towards the world of computerisation and AI in music. Computers weren’t completely foreign to the field at that time. In 1951, British scientist Alan Turing recorded the melodies to three songs, including God Save the King, with laboratory equipment. But for the Illiac Suite, the Illiac I was used to generate the music itself, utilising a series of algorithmic probabilities that were programmed into it by Hiller and Isaacson.

No one had ever used a computer to compose music in this manner before. Others, such as John Cage, helped lay the groundwork by experimenting with randomised composition methods in the early 1950s. Around the same time, Greek composer Iannis Xenakis developed a process he called “stochastic music,” whereby he based his compositions on mathematical formulas that were calculated by a computer. Hiller went one step further. “[He was] setting up algorithms for the computer to make choices,” says his daughter, Amanda Hiller, who was born several years after the suite’s completion. “But each one of those algorithms represented a set of particular views about what the musical outcomes could or should be.”

A native of New York City, Lejaren Hiller had played music for much of his life. He studied composition under Milton Babbitt and Roger Sessions and performed in student ensembles while he attended Princeton University, where he received his PhD in chemistry in 1947 at the age of 23. “He absolutely adored the standard [classical] repertory,” says Neely Bruce, one of Hiller’s former students. After contributing to the war effort as a chemical researcher, Hiller worked for DuPont in Waynesboro, Virginia, before taking his position at Illinois in the fall of 1952.

His arrival coincided with that of the Illiac I, which was unveiled that September and took up the better part of an entire room. Operating it was a laborious process that required entering code on to paper tape and waiting for it to blurt data back out – in the case of composing music, that data was then transcribed by hand into musical annotation. “Very few people got to interact with it,” says Bohn. “Even those who wrote programs for it never got in the same room with it.” Hiller, however, was one of them.

After working with the computer during research into synthetic rubber, Hiller began to think about how the algorithms could be applied to basic musical counterpoint exercises. Babbitt encouraged him to pursue the idea. The Illiac Suite’s four movements were a series of progressively more complicated experiments that mimicked different historical styles of classical music, from the Renaissance to Arnold Schoenberg’s 12-tone serialism of the early 20th century. At the time of the premiere, only the first three parts were completed. Sanford Reuning, the second violinist for that performance, is the only other living musician to have played that night. “It sounded like a first piece by a computer, if you know what I’m saying,” he says. “It was certainly not anything startling.”

The real departure came with the fourth movement, finished in autumn 1956, where Hiller drew on Markov chains, a particular kind of probability method where the music was based only on the note that directly precedes it, with little or no ability for the computer to memorise an overarching theme. After the plunked strings and skittering, sawing melodies of the opening movements, the fourth pops and percolates; it skips, stops, and starts, ratcheting up the intensity as it arrives at a series of dead ends and cliffhangers. Adding to the unpredictability was the fact that Hiller, devoted to the purity of his experiment, didn’t want to edit what the computer came up with. Thus, says David Rosenboom – who, as a student at Illinois, played violin on a 1967 re-recording of the suite – it can sometimes be awkward and unnatural. “It’s a hard piece to play,” he observes. “It requires technical skill, but at the same time, there’s a certain quirkiness about it that throws you off a little here and there as you jump around trying to play these big leaps.”

Hiller and Isaacson published a book about their research, Experimental Music: Composition with an Electronic Computer, in 1959. A review in the Chicago Tribune showed continued public skepticism, about whether a computer “can create music of lasting value or is an intriguing sidelight on the fascinating and fast growing science of automation”. Concerns about a computer takeover, still very real today among composers, missed the point back then says Amanda Hiller: “I certainly don’t think he ever thought a computer could replace a person as a composer.”

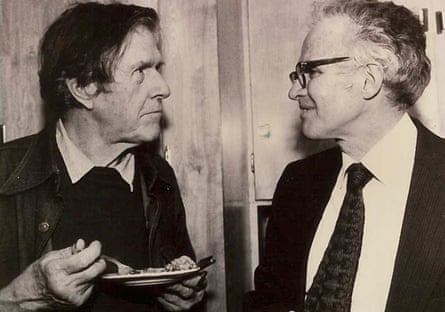

By autumn 1958, Hiller had transitioned full-time from the chemistry to the music department, where he spearheaded the establishment of Illinois’ Experimental Music Studio – only the second of its kind in the world, after the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. Cage himself did a residency at Illinois, working closely with Hiller on his landmark piece HPSCHD, which combined computer composition techniques with chance-based decision making from the I Ching. It made its premiere in an elaborate, multimedia performance that lasted five hours and included 52 tape players and 64 slide projectors at a campus auditorium in 1969. (Bruce was among the players.) The year prior, Hiller left to join the music faculty at the State University of New York at Buffalo, where he remained until his retirement, due to the onset of Alzheimer’s, in 1989.

Hiller ultimately assembled a large and highly eclectic body of music – “I’d say more of his compositions were non-digital [than digital],” his daughter points out – but he never fully shed the stigma of an amateur musician. He was a lightning rod among many of his musical peers, particularly those who worked alongside him at Illinois. “He was totally despised by certain members of the faculty. Because, you know, he touched a nerve in a very deep way,” says Bruce. He recalls Robert Swenson, who actually played cello at the suite’s premiere, complaining that “Hiller has a hotline to the international press.” Those at Buffalo, like conductor Jan Williams, were more receptive. “The fact that somebody started using computers only piqued my interest. I thought it was fabulous,” he says.

The Illiac Suite stands today as a monument to a certain postwar epoch, one where structuralist philosophies could be wed with digital technology and rule-based, mathematical songwriting techniques that date back as far as ancient Greece. “It’s a landmark piece in the development of the use of algorithmic thinking in music, which is now everywhere,” says Rosenboom. “Do I put it on and listen to it as dinner music? Not necessarily. But I think it was a very important experience in thinking about the musical form, and what that form can tell us and not tell us.” Bruce is more succinct: “I love the piece,” he says. “I think it’s fantastic.”

Ironically, Andrix and Reuning had little idea of the blowback that followed their first performance of the suite until later. It has since come to take on greater meaning for both. “I was a little surprised,” says Reuning, of when he came to appreciate the impact it made. “And I felt good, because I’d had a part in it and gave the first performance of it. That made me feel good to have been on the ground [floor] of this thing.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion