As a public defender, my job is to represent poor people charged with crimes. I’ve always had many clients behind bars. But the wall between us was never impermeable until COVID-19 hit.

Before the pandemic, I visited my jailed clients several times a week. I advocated for them in courtrooms. I worked their cases zealously. When COVID hit, my legal practice came to a screeching halt. Jail visits were abruptly cut off. The courthouse was shut down. As I huddled at home with my family, my clients were essentially sealed into mass isolation within the jail. I felt like I was riding away in a lifeboat, leaving everyone stuck on the ship to sink.

None of my clients got sick immediately. Initially, it seemed like the fact that they were isolated from the rest of the world, albeit in miserable conditions, might keep them safe. But staff enter and leave the jails every day, so it was only a matter of time before COVID crept in. When the virus first hit one of our pretrial detention facilities in the spring, it spread like wildfire through the crowded quarters. Our clients were effectively trapped in a burning building.

Everything I learned in three years of law school and 15 years of practice suddenly seemed completely useless. I filed motion after motion, trying to get people out of jail — and trying to ease my conscience. I had very little success. The pandemic created a sort of Catch-22: Clients at institutions still COVID-free were deemed ineligible for release because the danger to their health was not sufficiently imminent. And clients at institutions with active outbreaks were deemed unsafe to release because of the risk they might carry COVID into the community.

As I spun my wheels, more and more of my clients got sick.

In June, a healthy, 43-year-old client I’ll call Alan tested positive for COVID at a jail in Baltimore. He had no symptoms, but was shipped out to Hagerstown to be put in isolation. There, Alan was quarantined in a tent with other prisoners who had tested positive. Alan spent 13 days shackled to a bed in that tent. He was required to urinate in a bed pan. He had no access to a shower. He was not even allowed a phone call to his family to let them know he was alive.

I cannot overstate how stressful this time has been for families of incarcerated people. Visitation has been suspended and jails have been abruptly locked down, limiting communications with the outside world. Family members — whose hearts are in there with their loved ones — are left for days and sometimes weeks at a time imagining the worst.

In October, a 53-year-old client I’ll call Robert was nearing the end of his sentence at a federal prison in Fort Dix, New Jersey, when his roommate became ill with COVID. Prison staff sent the sick man back to the six-person dorm where he shared a bunkbed with Robert. The men were instructed to sleep “head to toe” to reduce the likelihood of transmission. When the prison finally tested the other men, days later, all had COVID. Unsurprisingly, this was just the start of a much larger outbreak: Nearly 1,500 of the 2,500 inmates at Fort Dix have now contracted COVID-19.

If a nursing home or hospital managed an outbreak this way, criminal investigations would follow. But when prisoners’ lives are at stake, we seem content to apply lower standards.

By November, all I could think to do was put money on the commissary accounts of the clients I’d tried and failed to get out, as well as the clients I knew I wouldn’t be able to get out. MoneyGram made a fortune off my guilt; they charge $8.95 per transaction to send money into federal prisons!

I finally won compassionate release for a client this week. It took five months and eight court filings. He’s 36 years old and has end-stage kidney failure. A doctor told the court he would likely die if he got COVID. I planned to pick him up from the prison in North Carolina. But the Bureau of Prisons put him on a bus before I could get there: a 10-hour ride with four stops in the middle of a pandemic.

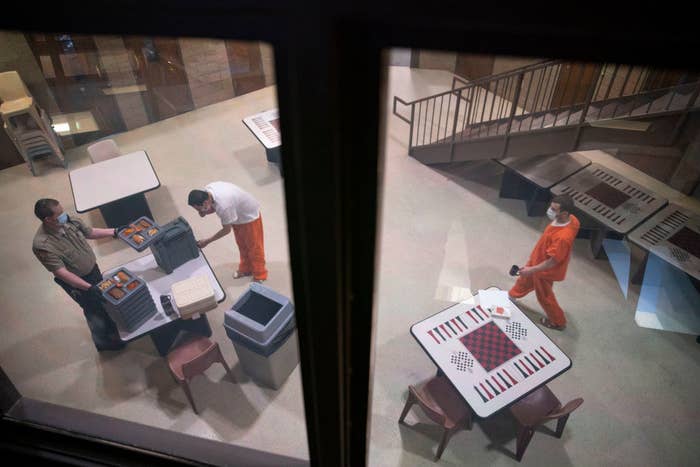

We continue to incarcerate more people, even as jails and prisons are uncontrolled breeding grounds for this virus. At the federal pretrial detention facility in Baltimore, where many of my clients are housed, one-third of the population has tested positive for COVID since January. The facility is now scrambling, reactively, to take basic precautions that should have been in place many months ago. While Maryland has prioritized vaccinating residents of nursing homes and other congregate facilities, no vaccines have been offered to my clients, who are equally at risk.

It has often been said that a nation’s greatness is judged by how it treats its most vulnerable members. We have tools to protect incarcerated people, including compassionate release, home confinement, clemency, and, now, a vaccine. We must use these tools unsparingly — or history will judge us harshly for it.

Liz Oyer is senior litigation counsel to the federal public defender for Maryland.