Glamour, with its qualities of mystery, realism and discretion, is notoriously difficult to define, but the photographs of 97-year-old Paolo Di Paolo provide definitive visual clues. For 14 years through the 50s and 60s, he photographed post-war Italy as it was, an agrarian society racing toward industrialisation.

Di Paolo’s reportage, of luminous movie stars, writers, directors of Italian cinema, agricultural and factory workers, and the poor – all in the spirit of empathetic curiosity – sometimes found their way into Il Mondo, a renowned 12-page political-intellectual weekly magazine, that counted Thomas Mann and George Orwell as contributors.

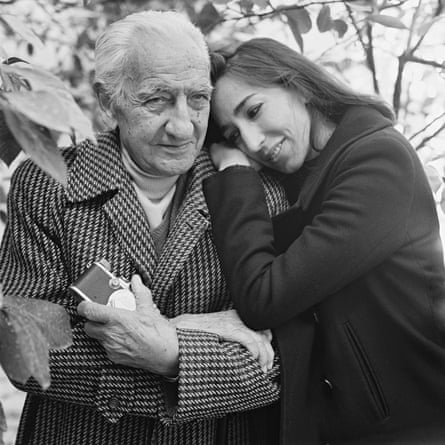

Di Paolo’s career is now being revisited – thanks in part to Italian fashion house Valentino’s creative director Pierpaolo Piccioli, designer of the year at the 2022 British fashion awards, ex-Gucci designer Alessandro Michele, who supported the first exhibition of Di Paolo’s work four years ago – but mostly to his daughter Silvia, who features prominently in The Treasure of His Youth, a compelling new documentary by photographer and film-maker Bruce Weber.

The film traces Di Paolo’s brief career during which he photographed Rome’s elite of arts and letters – “for pleasure,” he has said – as well as layers of postwar Italian society. Along the way, the former philosophy student – who started from humble beginnings in the small town of Larino, in the south-eastern province of Molise – trained his lens on Anna Magnani on the beach with her disabled son; Kim Novak ironing in her hotel room; Brigitte Bardot skipping up the steps in Spoleto; and Charlotte Rampling smouldering in a shepherd’s coat on the set of Sardinia Kidnapped in 1966. He was dispatched by Il Mondo on a Tuscan swimming tour with the poet and later film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, and called Marcello Mastroianni, Ezra Pound, Tennessee Williams, friends.

“His approach to photography was very spontaneous, the opposite of a paparazzo,” says his daughter Silvia Di Paolo, also the photographer’s archivist. “He considered himself an amateur, and people felt relaxed with him. He’d never try to provoke a situation.”

But a broken affair with an unnamed Roman society swan, and a photo editor who, in 1968, asked him to bring in “some spice” – code for a more aggressive style of the paparazzo – broke the spell. He hung up his Leica, placed 250,000 negatives, contact sheets and magazines in the cellar, and then for 40 years served as art director of the carabinieri, Italy’s regional police force. Silvia never knew her father had been a photographer – that is until she found his negatives in a cellar in the late 1990s – an event that set in motion his rediscovery. “He had wanted to remove any memory because quitting photography was for him a painful decision,” she says. Di Paolo’s exorcism of photography went so far, his daughter says, that there are no family pictures.

Her favourites include a shot of boys on a hill in Rome, another group looking into the car when her father and Pasolini were touring in a sports car; actress Capucine dancing at a party in Venice, a ball at Palazzo Rospigliosi in Rome that looks, she says, like the party scene in Visconti’s The Leopard; and Rampling in Sardinia. “It’s a moment of history that’s irreplaceable, and also because there was so much going on in culture, cinema and economics,” Silvia says.

“Even the poorest had a discreet elegance that today we don’t have”.

Valentino’s Piccioli, who came to see the Gucci-sponsored Mondo Perduto retrospective of Di Paolo’s work in Rome, then invited Di Paolo to photograph backstage at a Valentino show.

“In the fashion world they never say that someone in the same field is doing something so special, so I was very captured by that,” Di Paolo says. “Glamour is one thing, but the photos are also very intimate and private, and that gets you to a different level of inspiration. I think they both responded to the humanity.”

Crucially, perhaps, the stories that Di Paolo told were not complicated by commerce or sign-posted toward an ideology or projection of fantasy. “Nowadays we know almost everything about people and that has helped to destroy any sense of unreachability,” says his daughter. “My father said that even La Dolce Vita was a kind of lie invented by Frederico Fellini because no actress or actor would go around Via Veneto because people would be waiting to see someone famous.”

Actor and environmentalist Isabella Rossellini, who grew up in Italy at that time, says:

“Stylistically, we look at it with an eye to glamour now but at the time we did not look at it that way. Italy before the war was a very poor country, and after it became an industrial country. The period was electrifying with hope, the doors were open and everything was possible and the talents were revealed.”

An absence of artifice celebrated in Weber’s film, judged by many to be his strongest work since Let’s Get Lost, the 1988 documentary on the life of jazz trumpeter Chet Baker, invites comparison. In Weber’s view, Di Paolo could be to Italy what Henri Cartier-Bresson is to France or Cecil Beaton to Britain. “You can tell di Paolo was a friend of his subjects,” says Rossellini. “Bruce does that too – he pays a lot of attention to reportage because that tends to have more emotional impact. The glamour is in the talent and the intelligence, not in the clothes or the elegant gesture, and a photographer has to have a relationship and win the confidence of the subject, especially stars, who are guarded and subject to scrutiny.”

Weber first discovered Di Paolo’s work when he walked into a photographic store in Rome in 2012 and the owner put him in touch. “I didn’t know I was going to make a film, because sometimes you don’t and you start by taking still pictures and think about it,” he says. Best known as a fashion photographer, Weber, like Diane Arbus, studied under Lisette Model, who redefined documentary photography in America. “Show me a tree, but show me something the tree is going through,” Model would tell her students.

“Learning about Di Paolo, how and why he took those pictures, was like being in school again,” Weber says. “The work that survived after Di Paolo gave up photography are the pictures of the changing history of Italy, and that’s what I think is beautiful.”