In the 1950s, Tony Bennett watched with dismay as Black musicians like Nat King Cole and Duke Ellington were denied admission to concert hall dining rooms and hotels. The injustice he witnessed infuriated the young singer.

"I'd never been politically inclined, but these things went beyond politics," Bennett wrote in "The Good Life," his 1998 autobiography. "Nate and Duke were geniuses, brilliant human beings who gave the world some of the most beautiful music it's ever heard, and yet they were treated like second-class citizens. The whole situation enraged me."

That's why, when the artist and activist Harry Belafonte called up Bennett and asked him to join the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965, Bennett accepted without hesitation. He flew to Alabama and linked arms with his allies in the fight for justice.

Bennett, who died Friday at 96, entered the American musical pantheon thanks to his velvety vocals and seemingly effortless command of the standards songbook. But his civil rights activism is another essential part of his legacy, and he viewed his entrance into King's political movement as a crucial chapter in his life.

"When the march started, I had a strange sense of déjà vu," Bennett wrote in his 304-page autobiography. "I kept flashing back to a time twenty years earlier when my buddies and I had fought our way into Germany." Serving in World War II, Bennett's friendship with a Black serviceman was condemned by white Army officers.

"It felt the same way down in Selma: the white state troopers were really hostile, and they were not shy about showing it," Bennett wrote. "There was the threat of violence all along the march route, from Montgomery to Selma, some of which was broadcast on the nightly news and really helped to make the country aware of the ugliness that was still going on in the South."

Bennett was "terrified," he recalled, but Belafonte "kept his cool" and helped make sure everyone focused on the road ahead. (Belafonte died in April. He was also 96.)

Bennett did not walk all 54 miles. Instead, he went ahead to Montgomery so he could be there on March 24 to greet King and sing for the marchers alongside Ella Fitzgerald, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Sammy Davis Jr., Mahalia Jackson and others. The day after the Stars for Freedom rally, King delivered the "How Long? Not Long" speech on the steps of the Alabama state Capitol.

“I’m enormously proud that I was able to take part in such a historic event,” Bennett wrote in his autobiography, “but I’m saddened to think that it was ever necessary and that any person should suffer simply because of the color of his skin.”

When the Selma-to-Montgomery march came to an end, Bennett was driven to the airport by one of King's supporters, Viola Liuzzo, a white woman from Detroit who had three children. He later learned that she was killed by white supremacists on the drive back to Selma.

Bennett committed himself to the cause of racial equality in the decades that followed. He advocated for gifted Black artists and pushed the corporate music industry to release their records. He joined the artistic boycott of apartheid South Africa and performed for Nelson Mandela during the South African president's first state visit to Britain.

The crooner's abiding spirit of inclusion was clear to his children, including his eldest son, Danny, who recalled a "wonderful childhood."

In an interview with Good Housekeeping in 1995, Danny Bennett recalled "waking up to hear Count Basie and Duke Ellington jamming in our basement." Danny was "proud" that his father joined King's march "before it became fashionable among celebrities" to publicly crusade against racist discrimination.

"He is a good man and a good father," Danny Bennett said.

In 2007, Tony Bennett was inducted into the International Civil Rights Walk of Fame, a promenade at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta. The other inductees that year included the Hollywood icon Sidney Poitier, who died last year, and Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif.

Five years earlier, the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change, a nonprofit organization in Atlanta, bestowed on Bennett its 20th annual "Salute to Greatness" award. King's widow, Coretta Scott King, said the singer richly deserved the honor.

"Tony is not only one of America’s premier performing artists, but he was a deeply committed friend and supporter of my husband and the civil rights movement," she said in a statement at the time. "He has continued to support the efforts of the King Center to fulfill Martin’s dream, along with so many other great causes."

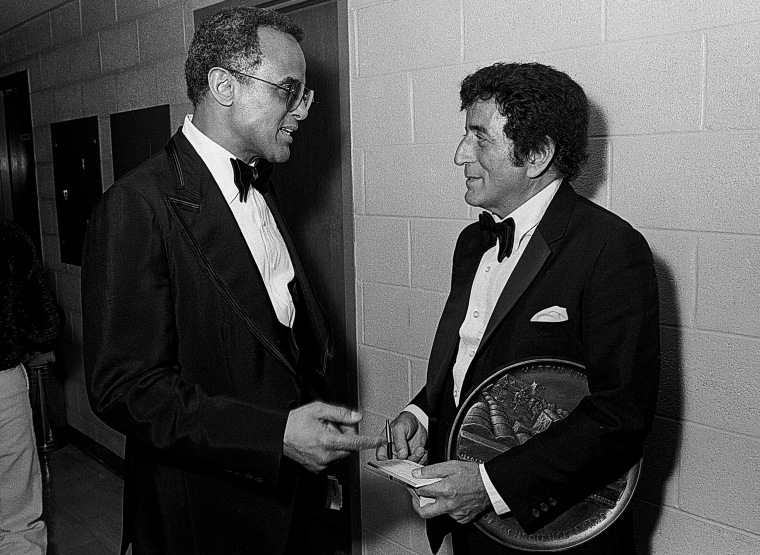

Bennett, for his part, told The Atlanta-Journal Constitution that he was "over the moon." In an interview with the newspaper, Bennett reflected warmly on his friendship with Belafonte and the inspiration he drew from the latter's example.

"Harry just reaffirmed for me that we’re all political animals when injustice is happening," Bennett said. "We’re all such a small speck in the face of the universe. Every single person on this planet is important and should be respected equally."